The Bleeding Yew Tree at Nevern Graveyard, Sjo, 1982

To my son Leif Sj-Jubb, of mixed Afro-American and Swedish descent, who was tragically killed on the 26 of August 1985 by patriarchal technology in a road accident at only 15 years of age in the south of France and to my kind and beautiful Swedish artist mother, Harriet Rosander, who died prematurely in her early fifties from poverty and a broken heart.

Monica Sj

To my mother, Mary Grace Carney, 19111948, and to Meridel LeSueur, 1900 to Infinity.

Barbara Mor

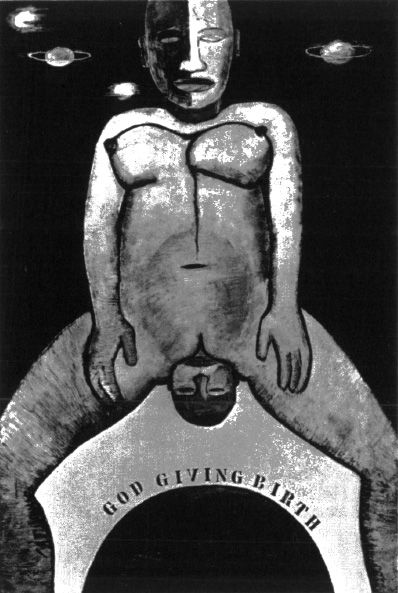

God Giving Birth, Sj. 1968

Tell them as I dying live, so they dying will live again.

The Moon, speaking through a tortoise to the African Bushmen

As the moon dieth and cometh to life again, so we also having to die, will live again.

California Indian prayer

CONTENTS

T his book is a wheel (she began). It begins and ends with the word beginning. Like a year, it has 4 parts, 52 chapters (4 seasons, 52 weeks: 13 lunations), though not symmetric. A She-Wheel, it unrolls Her Story: a description of the female journey through our human time on earth. Gyro-cycles of great myth and small data, poetry and numbers, dream and invention. Ice and fire: Cro-Magnon caves and Inquisitional burnings. Night and day: Her silent presence and His noisy history. And this new edition appears now in 1991: 9, the magic number of Muses, Crones, and that first mytho(menstrual)mathematically observed wheel: the Moon. One, which we are, and must become. Wheels within wheels within wheels: cellular, personal, local, global, cosmic: and begin again.

This is not planned; it just happens. As the world turns, as witches spin. As what disappears in the telescope reappears in the microscope; and vice versa. It seems to be organic.

I ride a bicycle: a 3-speed Schwinn (green, with food-gathering baskets), solidly built but in need of total overhaul. For 15 years, it has been my sole transportation (besides feet), and my Irish mood. (A wheel is a vehicle, a mood, a mode of direction.) My bike wheels are not precisely round: warped rims, threadbare tires, badly braked, punctured seasonally by goatheads and broken glass. Asymmetric, bumpy: my ride through life wobbles. But it moves, it works. It renews itself (strange oroboros wheels) stubbornly, to get the job done. The revolving bumps underline the rhythmic weirdness of the weather I must roll through, planetary and personal.

The earth too has its wobble.

As in winter. In the huge wobble of the Ice Age, humanity evolved itself. So most of this books work was done in unlikely winter. It was December 1976 when WomanSpirit magazine, for whom I read poetry, sent me Monicas pamphlet, mimeographed earlier that year in England. I lived on welfare in northern New Mexico, with my son and daughter. Weekly, I biked 2550 miles round trip to Taos (through wind, sage, dust, mud, lightning, snow) for food, supplies, and mail. Our adobe house, on a Spanish farm, was heated by pion wood in an old cast iron kitchen stove; I wrote at a wheel table (a wooden spool once used to wind electric cable). Working through winter, I doubled Monicas 100 pages; rewrote, restructured, added new material, sections, and titles. WomanSpirit could not print this enlargement. Four years later, in 1981, it was published by Rainbow Press in Norway (distributed in America by WomanSpirit). True to its winter nature: this book lay long dormant, but vital, under snow.

Winter again, 1984. Monica had made contact with a Harper & Row editor at the 1984 International Womens Book Fair in London. With this go-signal, I began writing the present book. Still in Taos, still on a bicycle; but the gears of welfare existence were grinding harder. Rent, food, utilities had doubled; but benefits (under Reagan) were frozen. So were we. Taos is 7,000 feet in the Southern Rockies, with ground snow through winter; temperatures of 30F on the deepest nights. I could afford to burn wood only 23 hours each evening; in daytime, the kitchen thermometer read 3840, from December through March. Through these months, I wrote 8 hours daily, sometimes wearing a down jacket; but the bulk impeded typing. Using material and notes from earlier writing and workshops Id done in San Diego (on womens religion, witchcraft, global politics), I expanded the 80 printed pages of the Rainbow Press Edition into the present book. Nightly, we huddled together (2 daughters and I) in sleeping bags on the living room floor, sandwiched by blankets, dogs, and cats. Ancient creatures in our cave. Bedrooms were cold storage; from the window of my youngest daughters room a foot-long icicle, 4 inches wide, crawled inside and down the wall. Our personal, microcosmic glaciation. It didnt begin to melt until mid-March. So be it.

Winter is the time of our content.

(In the Mule Mountains of southern Arizona, winter 1985, there was much cold, occult work to be done on the manuscript before it could be printed: text corrections and documentation, footnotes, bibliography, permissions, illustration selection and placement. I worked at the wheel table; 5,500 feet, no heat. The next winter, 1986, I proofed the galleys twice, sitting at a big table in a dark kitchen in a downtown barrio: a house of Tlazolteotl, Mexican Witch Goddess. Still no heat, no hot water. But by then I was in Tucson, where even winter is warm.)

A wheel is also a torture instrument, where witches were bound for punishment.

With my half of the advance, I left welfare. Publication was then delayed a year, until May 1987, to complete the manuscript and production work. Then, the first year of royalties was in the minus column, until the advance and authors share of publication costs were repaid. Meanwhile, I had no money. My daughters went to live with their brother and his wife in Albuquerque; into their basement storage went my belongings: bike, books, notes, typewriter.

And I became a Bag Lady on the streets of Tucson. For 13 months, off and on, I was one of those statistics: no job, no income, no home. All the heat Id not had during the icy months of writing curved around to hit me in the face. Intense 100+ calor of a desert citys brick-oven streets, from May through October. Windless; or the wind blew relentlessly electric, like a laundromat of open driers. I was on foot (age 51). I carried a big purple drawstring bag, full of my life (not much). Parked cars, boarded-up houses, barrio porches and backyards; garages used as shooting galleries; booths of 24-hour restaurants: this is where I slept. Nighttime helicopter surveillance and police raids entered my real dream. Also: solicitations for sex, threats of beatings and death, abandonment to nocturnal streets or the militant mercies of charity shelters. Days, I hung out in parks, plazas, courthouses, libraries. City fountains were multiple: to bathe, wash clothes, cool off; then you collect the coins. In air-conditioned oases (Burger King, Carls Jr.), 59 bought endless coffee refills, and free newspapers, i.e., culture. Public restrooms I also used for laundry and personal hygiene. I underwent malnutrition, began menopause, learned survival from my street partner: on the litmus paper of my own flesh, I kept notes of my experience.