Atlas Obscura

AN EXPLORERS GUIDE TO THE WORLDS HIDDEN WONDERS

J oshua F oer , D ylan T huras & E lla M orton

WORKMAN PUBLISHING NEW YORK

An Important Note to Readers

Though the publisher and authors have taken reasonable steps to ensure the accuracy and timeliness of the information contained in the book, readers are strongly encouraged to confirm details before making any travel plans. Location and direction information may change; GPS coordinates are approximations and should be treated as such. If you discover any out-of-date or incorrect information in the book, please let us know via .

Atlas Obscura was written in the spirit of adventure, and readers are cautioned to travel at their own risk and to obey all local laws. Some of the places described in this book are not open to the public and are not meant to be visited without appropriate permissions. Neither the author nor the publisher shall be liable or responsible for any loss, injury, or damage allegedly arising from any information or suggestions contained in this book.

The beginning of our happiness lies in the understanding that life without wonder is not worth living.

Abraham Joshua Heschel

CONTENTS

More than 350 feet below the surface, rowboats bob on a lake inside Romanias Turda Salt Mine. Now an underground amusement park, the mine produced table salt continuously from the 11th century until the 1930s..

INTRODUCTION

When we launched Atlas Obscura in 2009, our goal was to create a catalog of all the places, people, and things that inspire our sense of wonder. One of us had recently spent two months driving all over the United States searching out tiny museums and eccentric outsider art projects. The other was about to set off for a year of travel in Eastern Europe. We wanted a way of finding the curious, out-of-the-way places that dont often make it into traditional guidebooksthe kinds of destinations that expand our sense of what is possible, but which we would never be able to find without a tip from someone in the know. Over the years, thousands of people from all over the world have joined us in this collaborative project by contributing entries to the Atlas. This book represents just a tiny fraction of what our community has unearthed.

Though Atlas Obscura may have the trappings of a travel guide, it is in truth something else. The site, and this book, are a kind of wunderkammer of places, a cabinet of curiosities that is meant to inspire wonderlust as much as wanderlust. In fact, many of the places in this book are in no way tourist sites and should not be treated as such. Others are so out of the way, so treacherously situated, or (in at least one case) so deep beneath the surface, that few readers will ever be able to visit them. But here they are, sharing this marvelously strange planet with us.

This book would never exist without the incomparable and indefatigable Ella Morton, who has spent the last four years researching, writing, and crafting the physical object you hold in your hands. Nor would it exist without our incredible community of users, explorers, and contributors. Every one of you out there who added a place to the Atlas, made an edit, or sent in a photo: You are all our coauthors. Thank you. Though we have tried to check the accuracy of every fact in these pages, please dont book any plane tickets without first doing your own independent research. Or do! Just be ready for an adventure.

We often ask ourselves just how large a truly comprehensive compendium of the worlds wonders and curiosities could ultimately be. The economics of printing and the dimensions of the page set limits on what could be included in this book. But even our website, which faces no such constraints, can never be complete. There is an Atlas Obscura yet to be written that is as comprehensive as the world itself, for wonder can be found wherever we are open to searching for it.

Joshua Foer and Dylan Thuras

cofounders of Atlas Obscura

Europe

/ GREECE

CYPRUS /

GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND

ENGLAND

The Silver Swan

NEWGATE, DURHAM

This uncannily lifelike musical automaton mimics a full-size swan floating on a pond of spun-glass rods. Created in the 1770s, it uses three clockwork mechanisms to perform a 40-second routine set to calming bell-like music. When wound, the swan moves its neck from side to side to preen its feathers before dipping its beak into the pond and snatching up a tiny fish.

First displayed in British jeweler James Coxs Mechanical Museum, the swan was purchased by collector John Bowes in 1872 and is now housed in the Bowes Museuma French chateau in the north of England.

Bowes Museum, Newgate. A museum curator demonstrates the swan at 2 p.m. daily. The Bowes Museum is 17 miles (27.4 km) from Darlington railway station, which is a 2.5-hour train trip from London. Buses run from the station to the museum.

54.542142

54.542142  1.915462

1.915462

Walking, Eating, Moving Machines

Walking, Eating, Moving MachinesAutomatonsmechanical figures that move in an eerily lifelike mannerhave existed for centuries, but their heyday was during the 18th and 19th centuries.

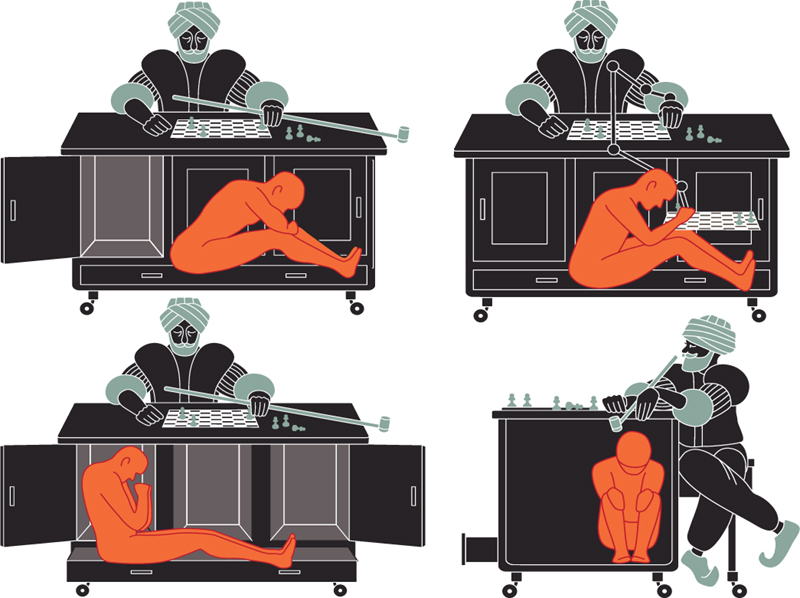

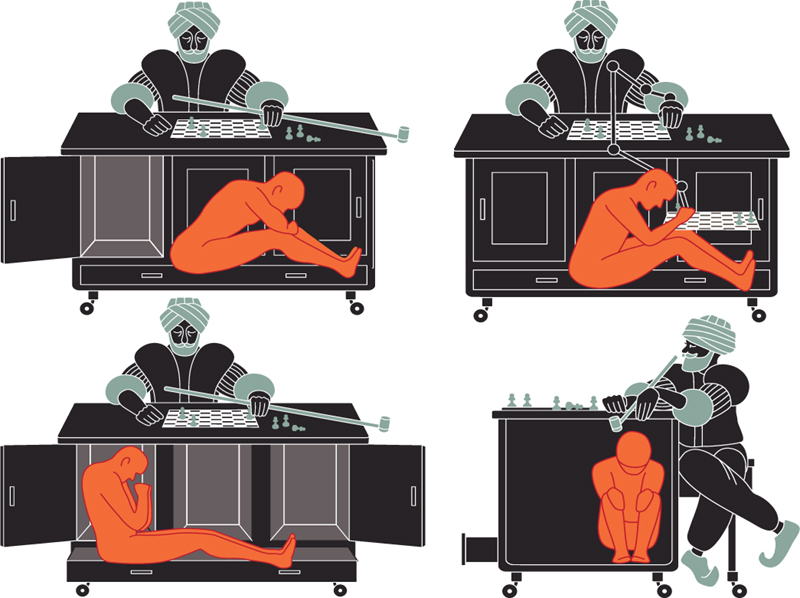

The Turk had a human microcontroller.

The Turk, built in 1770, was one of the most impressive: It consisted of a mechanical man in a turban who played chess against anyone willing to take him on. The machine toured the world, battling opponents like Napoleon Bonaparte and Benjamin Franklin. During the early 19th century, the Turks apparent intelligence and skill dazzled audiences and frustrated skeptics, who suspected a trick.

In the end, eagle-eyed observers, including Edgar Allan Poe, who encountered the Turk in Virginia in 1835, discovered the secret: a hidden human. The cabinet beneath the chess board held a squashed chess master who made every move by candlelight, pulling levers to operate the Turks arm and keeping track of the moves on his or her own board. The Turk was nothing but an elaborate hoax.

While the Turk was frustrating its opponents, genuine automatons delighted onlookers with their realistic movements. The Digesting Duck, the 1739 creation of Jacques de Vaucanson, flapped its wings, moved its head, ate grains, and shortly afterward defecated. The digestion process was not authenticthe ducks backside housed a reservoir of droppings that would fall in response to the amount of grains being eatenbut it was the first step toward what de Vaucanson hoped would eventually be a genuine eating machine.

54.542142

54.542142  1.915462

1.915462

Walking, Eating, Moving Machines

Walking, Eating, Moving Machines