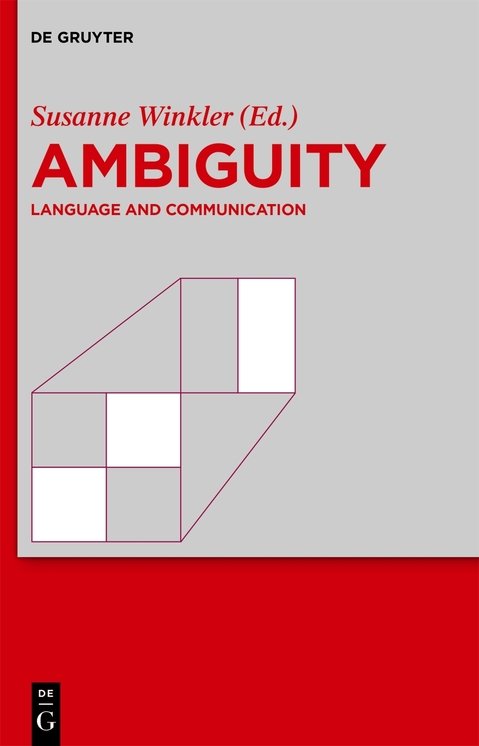

Susanne Winkler - Ambiguity

Here you can read online Susanne Winkler - Ambiguity full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2015, publisher: De Gruyter Mouton, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Ambiguity

- Author:

- Publisher:De Gruyter Mouton

- Genre:

- Year:2015

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ambiguity: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Ambiguity" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

This volume uncovers a great mystery about language: why can we communicate so effectively despite the fact that ambiguity is pervasive? Conversely, how do speakers use ambiguity to achieve a specific goal? Answers to these questions are provided in contributions from different academic fields: (psycho)linguistics, literary criticism, rhetoric, theology, media studies, law.

Ambiguity — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Ambiguity" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Thomas Wasow

In other words, natural language is highly ambiguous. A search of any good dictionary will reveal that most words have multiple definitions, and [as first noted by Zipf (1949)] more frequent words tend to be more ambiguous. Likewise, as computational linguists discovered a few decades ago, most strings of words that constitute well-formed sentences have multiple possible parses. For example, Martin et al. (1987) reported that their system assigned 455 distinct parses to the relatively simple sentence List sales of the products produced in 1973 with the products produced in 1972. In addition, there are other ambiguities that do not seem to be tied either to polysemous words or alternative parses. Among these is perhaps the most widely studied type of ambiguity, scope ambiguity. I will return to a more careful taxonomy of types of ambiguity in the next section.

If linguistic ambiguity is so common, why did Grice admonish us to avoid it? All of his maxims are presented as elaborations of the following general Cooperative Principle: Make your conversational contribution such as is required, at the stage at which it occurs, by the accepted purpose or direction of the talk exchange in which you are engaged (Grice 1975, 29). Among what he claimed is required in conversations is that the participants Be perspicuous (Grice 1975, 30). He evidently believed that ambiguity diminished perspicuity.

Grices intuition on this point seems very natural. If an utterance has multiple meanings, the task of the listener in ascertaining the speakers intended meaning is made more difficult, for it now includes the extra step of disambiguation. Moreover, the likelihood of miscommunication is increased, since it is possible that the listener will select an interpretation different from the one the speaker intended. Hence, efficient communication would seem to dictate ambiguity avoidance.

This intuitive argument for ambiguity avoidance gains plausibility from experience. We have all experienced situations in which listeners asked speakers which of two possible interpretations they had in mind for example, when someone asks, Do you mean funny peculiar or funny ha ha?. This disrupts and delays the conversation, but happens relatively frequently because it avoids an even less desirable consequence: a misunderstanding.

It is puzzling, therefore, that so much ambiguity persists in language. If functional considerations influence the direction of language change (as one might expect), then changes that reduce ambiguity would seem to be strongly favored. Yet there is little, if any, evidence that ambiguity in languages has decreased over time.

Grices intuition that ambiguity is an undesirable property of language is widely shared. Many people, including a number of linguists, have proposed that various properties of language are explainable as ways of avoiding ambiguity. For example, the following passage from a website on the basics of Latin (Gill, under Word Order Latin and English Differences in Word Order) implicitly appeals to the need to avoid ambiguity as to which argument in a transitive clause is subject and which is object:

The reason Latin is a more flexible language in terms of word order is that what English speakers encode by position in the sentence, Latin handles with case endings at the ends of nouns, adjectives, and verbs. English word order tells us that what is the subject is the (set of) word(s) that comes first in a declarative sentence, what is the object is the set of words at the sentence end, and what is the verb separates subject from object.

Essentially the same argument is made by Fries (1940) in comparing the word orders of Old English and Modern English: what once was communicated with inflections came to be communicated through more rigid word order. Fries (1940, 207) cites Sapirs (1921) distinction between concepts whose expression is essential or unavoidable and those whose expression is dispensible or secondary.

If, for example, we are to say anything about a bear and a man in connection with the action of killing, it is essential and unavoidable that we indicate which one did the killing and which one was killed. [] On the other hand, whether the killing took place in the past, the present, or the future, whether it was instantaneous or long drawn out, whether the speaker knows of this fact of his own first-hand knowledge or only from hearsay, whether the bear or the man has been mentioned before-these matters are of the dispensable or secondary type and may or may not be expressed.

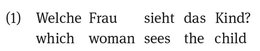

In other words, every language must have mechanisms for expressing the basic argument structure of a clause (who did what to whom), and particular sentences should not be ambiguous with respect to argument structure. Something close to this idea is defended in Hankamers (1973) paper Unacceptable Ambiguity, which proposes a universal condition to prevent certain kinds of transformational rules from introducing structural ambiguity. He argues, for example, that a German sentence like (1) must be interpreted with the initial noun phrase functioning as the subject, even though both NPs happen to have identical nominative and accusative forms.

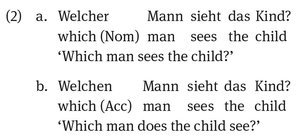

If the initial NP were masculine, case morphology could distinguish its grammatical role, so both (2a) and (2b) are possible.

But Hankamer claims that (1) only has the

Bouma (2011) cites Jakobson (1936) as having similarly argued that case syncretism in subject and object can lead to word-order freezing, and Flack (2007) claims that the same is true of Japanese. Thus, the idea that languages do not permit ambiguity with respect to argument structure is a recurrent one.

Linguists have also cited avoidance of temporary ambiguities that might add to processing complexity as a reason for particular linguistic structures. For example, Langacker (1974, 631) writes the following:

that -deletion is not permitted in non-extraposed subject clauses:

(3) That he has never played rugby before is apparent.

(4) *He has never played rugby before is apparent.

Viewed in purely syntactic terms, the non-deletability of that in 3 is surprising and must be treated as exceptional in some fashion hardly a satisfying state of affairs. On the other hand, a functional perspective enables us to begin to explain why English should observe this restriction. If that -deletion were permitted in nonextraposed subject complement clauses, the resulting surface structures, such as 4, would present the language user with certain processing difficulties; in this instance, the listener would naturally hypothesize (mistakenly) that He has never initiates the main clause, since nothing would signal its subordinate status until later in the sentence. The retention of that in sentence-initial complement clauses enables the listener to avoid this processing error.

In short, the ungrammaticality of (4) is explained through appeal to the undesirability of leaving the basic structure of the sentence ambiguous until the copula is encountered.

These are just a few examples of a very common form of explanation about language: languages and their speakers are presupposed to prefer forms that are unambiguous, and facts about grammar or usage are motivated by ambiguity avoidance.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Ambiguity»

Look at similar books to Ambiguity. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Ambiguity and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.