Valasia Isaakidou and Peter D. Tomkins

A Brief History of Cretan Neolithic Studies

In 1900, Arthur Evans and Duncan Mackenzie first encountered Neolithic levels in deep soundings at Knossos. Study of pottery from these soundings resulted in publication of a tripartite phasing of the Knossos Neolithic sequence (Mackenzie 1903) and reports soon followed on excavations at Phaistos (Mosso 1908) and at the small upland site of Magasa (Dawkins 1905). The Cretan Neolithic was thus discovered only a few months after its Thessalian counterpart and initially aroused considerable scholarly interest (Evans 1901; 1928), but was thereafter overshadowed by research in northern Greece.

One reason for this neglect of the Neolithic of Crete was undoubtedly the extraordinary wealth of the Minoan Bronze Age that still dominates archaeological research on the island today. Prehistorians working in Thessaly have largely been free of such distractions and Tsountas was able to expose the Neolithic settlements of Sesklo and Dimini (Tsountas 1908) on a scale that was (and remains) impossible beneath the Cretan palaces. On the other hand, Neolithic pottery with distinctive styles of painted and incised decoration made Thessaly an attractive target for culture historians seeking to build intra- and inter-regional relative chronologies ( e.g. , Tsountas 1908; Wace and Thompson 1912; Grundmann 1934; Milojcic 1960). The abundance of highly visible tells in Thessaly also encouraged a long tradition of research on a regional scale ( e.g. , Tsountas 1908; Wace and Thompson 1912; Grundmann 1937; Theocharis 1973). By contrast, the Neolithic of Crete received little further attentionin the field or in printuntil the 1950s, when Furness reworked the ceramic chronology of Mackenzie and Evans (Furness 1953), Levi resumed investigation of the Neolithic levels at Phaistos (Vagnetti 1973; Vagnetti and Belli 1978), and John Evans was invited to do the same at Knossos, as he describes below (Evans this volume).

John Evans two campaigns at Knossos (195760, 196970) set new standards in stratigraphical and contextual excavation, in the application of radiocarbon dating and in the recovery of bioarchaeological as well as artefactual remains (Evans 1964; 1968; 1971; Jarman and Jarman 1968). Perhaps the most dramatic result of renewed excavation was the exposure of an initial aceramic layer at the base of the Knossos mound. The radiocarbon dates had two principal consequences. First, they demonstrated that the established tripartite periodisation of the Cretan Neolithic was considerably out of step with that for mainland Greece (Tomkins this volume, ). This reinforced the impression, created by the relative paucity of distinctively decorated ceramics and of systematic research, that the Neolithic culture of the island had developed in isolation from the rest of the Aegean. Secondly, as elsewhere, radiocarbon dating and subsequent calibration stretched the chronology of the Cretan Neolithic so that it began as early as the beginning of the seventh millennium BC. Bioarchaeological research, in collaboration with the British Academy-funded Early History of Agriculture project, involved pioneering attempts at systematic retrieval (using dry-sieving and flotation) of faunal and botanical remains and showed that domestic animals and crops were present from the earliest aceramic phase of occupation. The early date of this Initial Neolithic phase, coupled with the bioarchaeological results and the insular location of Knossos, earned the site a prominent place in discussions of the origins of agriculture and neolithisation of Europe ( e.g. , Higgs and Jarman 1969). Also influential on subsequent research was John Evans model (based on a series of sondages cut for this purpose in his second excavation campaign) of the steady expansion of the Knossos settlement through the Neolithic (Evans 1971; 1994).

From the 1970s onwards, Neolithic studies in mainland Greece, and especially Thessaly, increasingly shifted away from chronological and culture historical problems to explore settlement patterns, demography, subsistence practices, social change and the dynamics of production and consumption of material culture ( e.g. , Theocharis 1973; Hourmouziadis 1979; Halstead 1981; 1989; Kotsakis 1983; 1992; Washburn 1983; Cullen 1984; Vitelli 1989; Perls 1992). In a similar vein, Broodbank and Strasser (1991) interpreted the initial Neolithic colonisation of Crete in terms of a planned transfer of people and domesticates, Lax and Strasser (1992) proposed that early colonists played a role in the extinction of the islands endemic fauna, and Broodbank (1992) related the growth of Neolithic Knossos to changes in material culture and to a suggested increase in the proportion of cattle. These studies were based on preliminary reports from John Evans excavations and the empirical basis of Broodbanks paper was rapidly questioned (Whitelaw 1992).

From the late 1990s, a series of independent projects tackled re-analysis and publication of Neolithic material from Crete, principally from Knossos with encouragement from John Evans, but also from Phaistos and other sites. Some new excavation also took place at Knossos (Efstratiou et al. 2004), but the focus of fieldwork in recent years has shifted away from Knossos to recognition in surface surveys (and in some cases excavations) of numerous short-lived sites from the last stages of the Neolithic in other parts of the island ( e.g. , Vasilakis 1987; 1989/ 90; Vagnetti et al. 1989; Manteli 1992; 1993; Vagnetti 1996; Branigan 1999; Nowicki 2002). This new fieldwork finally offered the opportunity to place the long occupation sequence at Knossos in a regional context, although excavation of short-lived FN sites had by and large failed to provide the stratigraphic evidence needed to resolve significant outstanding problems of relative and absolute dating.

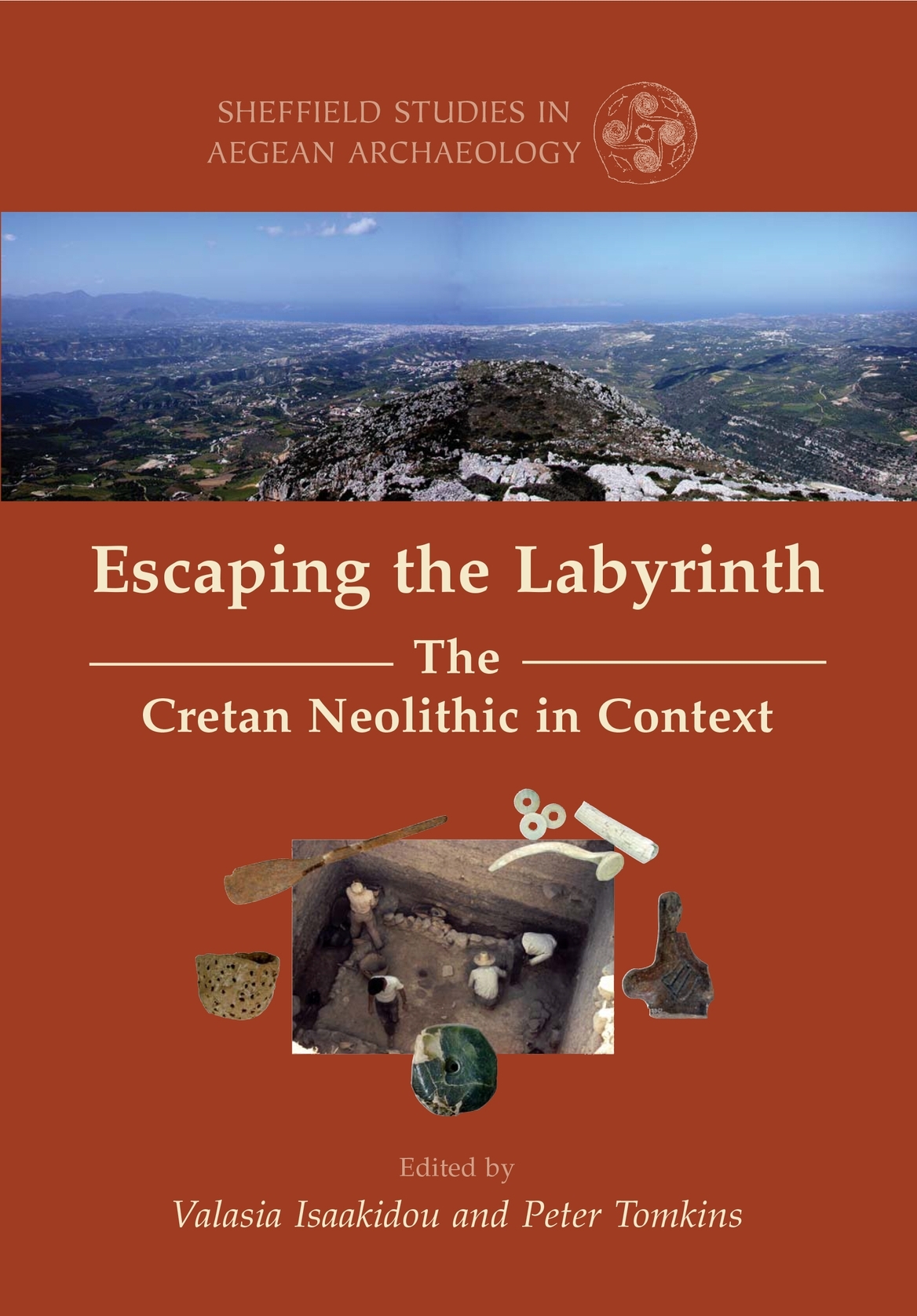

The Round Table

With post-excavation study at Knossos well advanced and with increasing fieldwork and study projects in other parts of the island, it seemed that research into the Neolithic of Crete had finally achieved the critical mass that might enable significant advances in the field to be made. To this end it was decided to devote one of the informal annual Round Tables of the Sheffield Centre for Aegean Archaeology to the theme of Rethinking the Cretan Neolithic. The aims of the meeting were to present some of the diversity of current research into the Cretan Neolithic, to explore ways of reconnecting it with Neolithic scholarship in the rest of the Aegean and to re-examine how the Cretan Neolithic is conceptualised. The Round Table, held on 2729 January 2006, brought together the group of scholars engaged in post-excavation work on Neolithic Knossos (Evans, Conolly, Isaakidou, Mina, Strasser, Tomkins, Triantaphyllou and Whitelaw) and colleagues engaged in similar study and fieldwork elsewhere in the island (DAnnibale, Di Tonto and Todaro, Galanidou and Manteli, Nowicki, Papadatos). To counter the isolation of Cretan Neolithic studies, we also invited papers from colleagues active in Neolithic research elsewhere in the Aegean or Mediterranean (Broodbank, Halstead, Kotsakis, A. and S. Sherratt). In addition, Adonis Vasilakis presented a poster on his own important excavations (published elsewhere) and, together with Keith Branigan and Peter Warren, helped to guide discussion. The result was a series of diverse and highly stimulating papers and a lively and enriching exchange of views that bodes well for the future health of Neolithic research in Crete. Of those who presented papers to the Round Table, only Todd Whitelaw was unfortunately unable to contribute to this resulting volume.