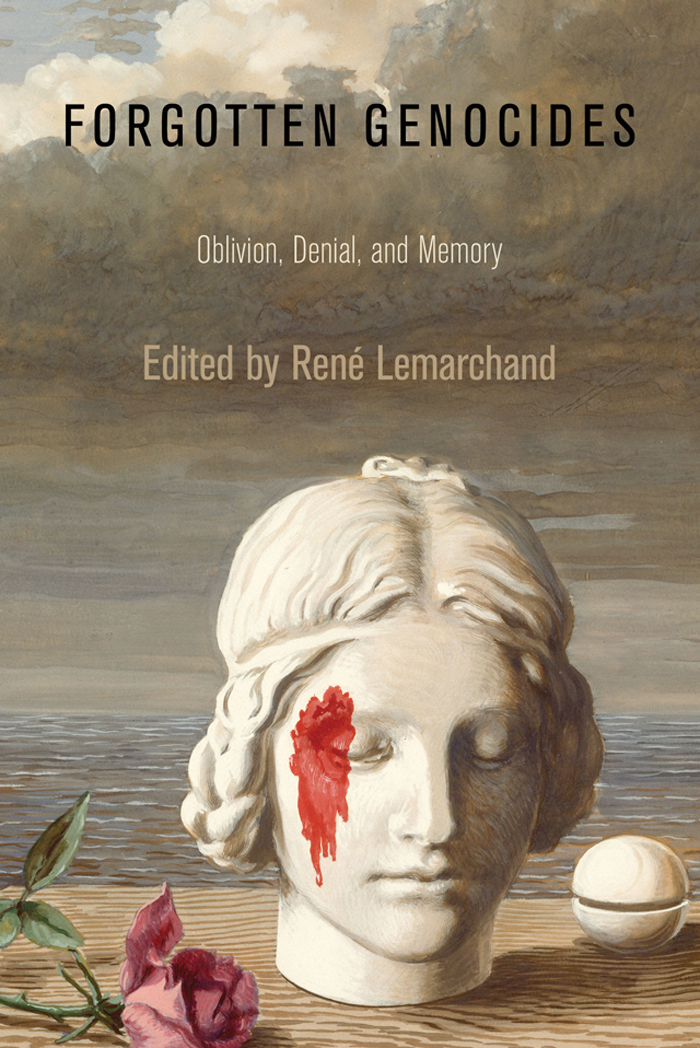

Forgotten Genocides

Pennsylvania Studies in Human Rights

Bert B. Lockwood, Jr., Series Editor

A complete list of books in the series is available from the publisher.

Forgotten Genocides

Oblivion, Denial, and Memory

Edited by

Ren Lemarchand

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PRESS

PHILADELPHIA

Copyright 2011 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Forgotten genocides : oblivion, denial, and memory / edited by Ren Lemarchand.

p. cm.(Pennsylvania studies in human rights)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN: 978-0-8122-4335-2 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Genocide. 2. Ethnic conflict. 3. Political violence. 4. Crimes against humanity. 5. War crimes. I. Pennsylvania studies in human rights.

HV6322.7 .F67 2011

364.151

2011011293

Contents

Ren Lemarchand

Filip Reyntjens and Ren Lemarchand

Ren Lemarchand

Dominik J. Schaller

Shayne Breen

Claude Levenson

Choman Hardi

Hannibal Travis

Michael Stewart

Preface

My main motivation for putting this book together stems from my lifelong immersion in the tragic destinies of Rwanda and Burundi. No two other countries in the continent have experienced genocidal bloodshed on a comparable scale. That they happen to share much the same ethnic map, a mutually understandable language, and were once traditional kingdoms before they became republics make their divergent paths to modernity all the more intriguing. And while genocide is the overarching theme of their blood-stained trajectories, the parallel should not mask the differences: the victims in each state belonged to different communities (Tutsi in Rwanda, Hutu in Burundi) and, unlike what happened in Rwanda in 1994, the perpetrators in Burundi won the day, insuring that the story be told from the victors point of view. Hence the paradox inscribed in their agonies: while Rwanda suddenly emerged from decades of obscurity to become a synonym for a tropical version of the Holocaust, very few in the United States or elsewhere outside Africa have the faintest awareness of the scale of human loss suffered by Burundi twenty-two years earlier. That about three times as many people died in Rwanda is no reason to ignore the fate of its false twin to the south.

Because of its even more appalling reenactment in Rwanda, and the connection between them, my early encounter with the Burundi slaughter stays in my mind as if it happened yesterday. I am still haunted by visions of school children being rounded up and ordered to get into trucks, like sheep taken to the abattoir, only to be bayoneted to death or their skulls crushed with rifle butts on their way to the mass graves. Compounding the moral revulsion I felt in the face of the first genocide recorded in independent Africa was the death of many close friends, a loss I would experience again, twenty-two years later in Rwanda. Notwithstanding the retributive character of the killings, the vehement denial by Burundi officials at the time that anything even remotely resembling a genocide had happened is what I found particularly difficult to swallow. All genocides have their deniers, and Burundi is no exception. Retrospectively, what made denial in this case so unusual is that it went virtually unchallenged. Equally astonishing is the manipulation of the facts, not just by Burundi officials but by Western scholars and journalists, with a view to shifting the onus of genocidal guilt to the victim group, while presenting the state-sanctioned killings as a legitimate repression.

As I read the essays in this volume I came to realize there is nothing exceptional about the misrepresentations surrounding the Burundi tragedy. Every genocide is unique in terms of circumstances and motives, but the deliberate concealment or manipulation of the facts by the perpetrators is more often the rule than the exception. This is not to exonerate survivors from similar distortions, only to emphasize the difficulties involved in getting at the truth.

To reiterate a commonplace observation, many more genocides have been committed through history than is recorded in human memory. Although the cases discussed here are but a limited sample in a litany of abominations going back to biblical times, they give us is a sense of the diversity of contexts out of which emerged the same hideous reality. The Holocaust will forever remain the archetypal frame of reference for taking the measure of human perversity. But as readers of Cathie Carmichaels splendid inquest into Genocide Before the Holocaust (2009) must surely realize, fixation on the Holocaust is likely to deflect our attention from the similarly horrendous crimes that preceded (and followed) the Jewish apocalypse, as if each generation needed to be reminded of the horrors of the past. This is only one of the many lessons to be learned from these essays.

I am willing to concede a touch of hyperbole in the title of this book. Needless to say, none of the events it seeks to illuminate have been forgotten by the descendants of the victims. Nor are they likely to be forgotten by those readers who came across the rare accounts of such cases that have appeared in academic publications, notably those on the Gypsies, on Anfal, and Burundi, in the edited volume by Samuel Totten and William S. Parsons, Century of Genocide (2009). Some may wonder, with reason, whether it is at all appropriate to describe the tragedy of the Herero as a forgotten genocide; my principal motive for doing so is that in the course of his research Dominik Schaller has unearthed a rich trove of new materials, which cast a singularly lurid light on the genocidal enterprise of the colonial state. Furthermore, there can be little doubt that the killings of the Herero, like the other tales of horror discussed in this book, are scarcely remembered by the wider public or ever entered the consciousness of some prospective readers.

Although my interest in the comparative study of genocide is inseparable from my work on Central Africa, I have derived enormous intellectual profit, and no little stimulation, from the seminars I taught from 1998 to 2003 at the University of California at Berkeley, Smith College, Brown, Concordia (Montreal), and in Europe at the Universities of Bordeaux, Copenhagen, and Antwerp, all of them centered on the analysis of genocide from a broad historical perspective. I would like to take up this occasion to express my sincere gratitude to those colleagues of mine who made it possible for me to expand my horizons, geographically and intellectually. Among others, Jacques Smelin, Research Director at the Paris-based Centre National pour la Recherche Scientifique CNRS) and Director of the Online Encyclopedia of Mass Violence, has been particularly generous of his time in sharing with me his insights and critical commentaries on issues related to this book. I also owe a huge debt to my seminar students here and abroad for inviting me to bounce ideas off them and forcing me to call into question many of the assumptions I once took for granted, including the notion that genocide is just as straightforward a concept as the circumstances that bring about the tectonic slide of intergroup enmities into the abyss of mass murder.