Aperitif

AND THEN THERE WERE CRAFT SPIRITS

2013|Boston

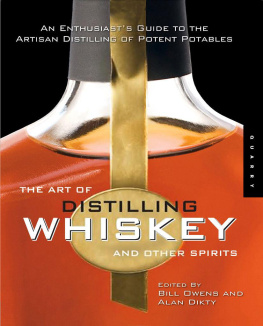

I t was an ungodly hour to be drinking rum. I wanted, however, to see Buffalo Bill Owens, who opened one of Americas first brewpubs, and this was my chance. We had spoken by phone and e-mailed several times for my history of American craft beer, yet had never actually met. He had moved on from craft beer to another interest and would be in Boston that weekend in June 2013 to tour a new distillery that his trade group, the American Distilling Institute, helped promote. He knew I lived in nearby Cambridge. Would I like to meet?

The craft beer history had been published, but yes, meeting Bill would be a treat, even if it meant an early Saturday wake-up, as well as a subway ride and a long walk, to a more remote area of South Boston. Two first cousins had started GrandTen Distilling in 2011 in an old iron foundry, one of several long-docile warehouse spaces in Southie, an area that had transitioned from industry and organized crime to biotechnology and food trucks. Matt Nuernberger had an MBA and therefore handled the business side, and his cousin Spencer McMinn was a chemistry PhD who handled the distilling. Matt and Spencer were both there when I arrived, as was Bill, dressed in a black vest over an orange short-sleeved shirt, square brown glasses perched on a perfectly triangular nose just above a thin, white mustache that matched his salty, spiky hair. Bill held court throughout the entire tour, which included a rundown of GrandTens equipment, such as its gorgeous copper stills, and which ended with samples at the small bar toward the former foundrys front.

I sipped GrandTens rum... and was pleasantly blown away. Fresh and flavorful, clean in mouthfeel and appearance, it tasted like no other spirit I had consumed beforenone of that acrid, overly alcoholic taste so common to bigger brands. Instead, the spirits components were distinct and upfront, particularly the molasses, which provided the rums sugar. Here was a spirit you could savor, not simply knock back to get drunk quickly.

As novel as their products tastedI also sampled a whiskey and a ginGrandTens operation was thoroughly familiar, from the backstory to the vibe to the physicality. The place looked and felt like a craft brewery: relatively small and, by necessity, cramped; in an area of town that could certainly use the trade; the libations produced in small batches with more traditional methods anathema to bigger, macro-competitors (which, to be honest, probably did not see GrandTen as much of a competitor in 2013); and the cousins Nuernberger and McMinn casual in appearance and tone but unapologetically earnest about what they were doing. Business-wise, too, the distillery was familiar: a start-up in the drinks business crafting its wares for sale locally and not much beyond. The emphasis was on craftsmanship and connectedness, not putting a bottle in everyones dining (or dorm) room or liquor cabinet. It was much the same ethos that craft brewers had long emphasized, beginning back in the 1960s and really picking up steam in the 1980s, when entrants such as Owens himself decided to start making small batches of beer with traditional methods and ingredients, and selling it locally and not much beyondin Owenss case, in the same Northern California restaurants where the beer was made.

I easily discovered that I was far from the first to make this spirits-beer connection. The whole thing seemed like a rerun at first glance; only the drink had changed. Connecting what was being called craft spirits with craft beer seemed de rigueur in media coverage of the emerging trend. And several craft distilleries seemed to understand that journalists and consumers expected that. The packaging of many craft spirits, and the official backstories provided on websites and in marketing materials, consciously aped and echoed the tradition-heavy, antimacro ethos of craft beer. It worked beautifully to some degree. An industry survey in 2016 found that nearly 60 percent of store owners and 25 percent of bar and restaurant owners thought craft spirits would perform like craft beer sales-wise over time.

Yet I soon discovered that there were more than a few craft distilleries behaving disingenuously when it came to such craft beerlike packaging and marketing. Simply put, there was no tradition, and they were quite macro in a lot of respects. They bought in bulk what the industry called neutral, or rectified, spiritsalmost 100 percent pure ethyl alcohol that could then be cut and flavoredand simply rebottled it with craft-like labels complete with bucolic shots of countryside distilleries and talk of local origins. (The only thing local was the bottling.) Or they bought the finished product and did much the same thingrebottled it with their own misleading labels. There were no government regulations prohibiting these operations from doing either. These faux craft distilleries, I soon realized, accounted for a not insignificant number of what the media often labeled craft. If they were not a majority, then they were certainly a sizable minority.

Then there was the plain fact that many macro operations produced fine spirits in what for them were relatively small batches. This was particularly true of whiskeys, especially that American original, bourbon. A distillery did not have to be small in size and independently owned to craft a solid whiskey, or even a solid vodka or gin. In fact, it could be advantageous to be large, given that many of the nations biggest distilleries were also the oldest and therefore awash in the most institutional knowledge about how to make a particular spirit (again, especially whiskey).

These dual realities stood in stark contrast to the craft beer that the media and the industry often compared craft spirits with. There were phantom craft beers, to be suremacro-brewery products that certainly looked micro. But they rarely, if ever, tasted so. The bigger breweries often used shortcuts, including chemical additives and nontraditional ingredients such as rice, and favored the sort of voluminous output that can be bad for beer, a drink usually best when freshest and therefore closest to its source. Macro-distilleries smaller-batch spirits, on the other hand, whatever their packaging, often did taste as good as, if not better than, their tinier counterparts offerings. It was all a muddle.

Try as the media and others might, they could not quite fit craft spirits into the same neat taste rubric as craft beer.