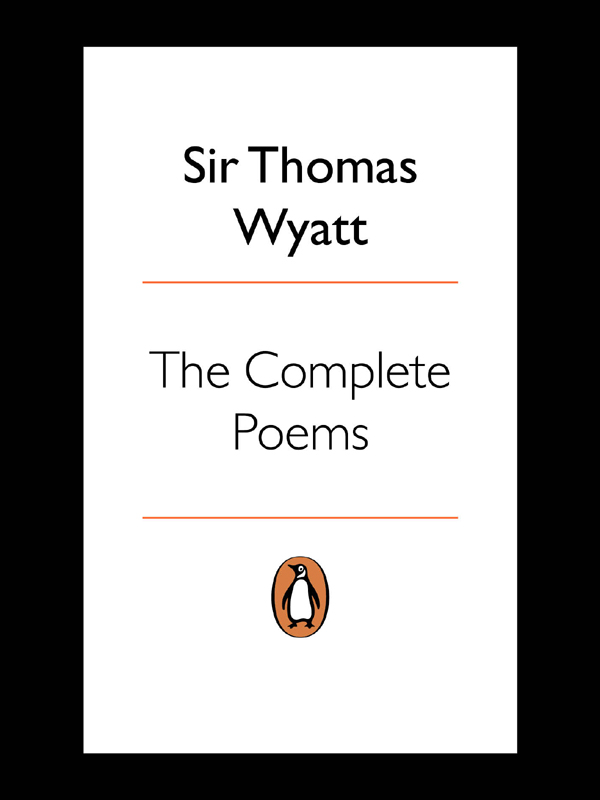

PENGUIN BOOKS

UK | Canada | Ireland | Australia

New Zealand | India | South Africa Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published 1978 Introduction and notes copyright R. A. Rebholz, 1978, 1997 All rights reserved ISBN: 978-0-141-96916-9

THE BEGINNING

Let the conversation begin Follow the Penguin Twitter.com@penguinukbooks Keep up-to-date with all our stories YouTube.com/penguinbooks Pin Penguin Books to your Pinterest Like Penguin Books on Facebook.com/penguinbooks Listen to Penguin at SoundCloud.com/penguin-books Find out more about the author and

discover more stories like this at Penguin.co.uk PENGUIN CLASSICS

PENGUIN ENGLISH POETS

GENERAL EDITOR: CHRISTOPHER RICKS

WYATT: THE COMPLETE POEMS

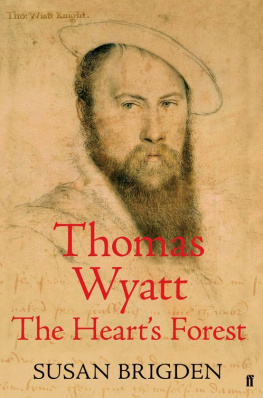

Thomas Wyatt was born around 1503 at Allington Castle in Kent.

His father was Privy Councillor to both Henry VII and VIII. The young Wyatt appeared as a minor functionary at the court of Henry VIII and in the same year, 1516, entered St Johns College, Cambridge. Thereafter, he spent most of his adult life in service at the court. His first appointments abroad were to France and Italy, where he may have been in contact with the leading writers of the time, after which he translated Plutarchs Quiet of Mind for Catherine of Aragon from the Latin version of Bud; it was published the following year. From 1528 to 1530 Wyatt was High Marshal of Calais. Between 1537 and 1540, he was Ambassador to the court of Emperor Charles V and travelled to France, Spain and The Netherlands.

After the disgrace and execution of his friend and patron, Thomas Cromwell, Wyatt was arrested for treason in 1541, but released and pardoned two months later. Taken back into royal favour in 1542, he died of a fever while on a diplomatic errand for Henry VIII. The bulk of his poems began to be published five years later. R. A. Phil. Phil.

Rebholz joined the faculty of Stanford University in California in 1961 and is a professor there. His special field is Renaissance literature, with emphases on the development of the short poem and Shakespeare. His publications include The Life of Fulke Greville, First Lord Brooke, a contemporary of Shakespeare, and articles on the poems of Greville, Wyatt and Shakespeare.

Preface

In this edition I have printed all the poems attributed to Sir Thomas Wyatt in the three most important modern editions of his poems those by George Nott (181516), A. F. Foxwell (1913), and Kenneth Muir and Patricia Thomson (1969).

But the reader should not assume that all the poems in this book were written by Wyatt. The problem of determining which poems Wyatt wrote is as yet unsolved and is likely to be solved only by a brilliant linguist who knows how to use a computer with great skill. Not possessing those attributes, I have had to rely on simpler evidence and procedures. The external evidence for Wyatts having written a poem can be arranged in a hierarchy of authority. No one doubts that Wyatt wrote the poems in his own handwriting in Egerton Manuscript 2711 in the British Museum; in the case of the Penitential Psalms, the nature of some of his revisions proves that he was composing the poems in the manuscript. (I say almost because it is conceivable that he was improving poems of another writer, just as his poems were improved within a few years of his death.) Next, in the margin by some of his poems in the Egerton MS, there is written Tho. or Tho, presumably an attribution to Wyatt by a person sufficiently intimate with him to call him by his Christian name. or Tho, presumably an attribution to Wyatt by a person sufficiently intimate with him to call him by his Christian name.

In a different hand, Wyat appears in the margin by some poems; that attribution, though less intimate in its reference, still has considerable authority. The first poems attributed to Wyatt in print were his Penitential Psalms, printed in 1549; but this edition merely confirms the fact of his authorship already inferred from his having composed the poems in the Egerton M S. When we come to the first edition in which other poems were attributed to Wyatt Richard Tottels Songs and Sonnets, usually called Tottels Miscellany we encounter an editor or editors apparently conscientious about the matter of authorship: one of the poems attributed to Wyatt in the first edition of 5 June 1557 was moved to a section entitled Uncertain Authors in the second edition of 31 July 1557. Tottels attribution of poems to Wyatt probably possesses, therefore, as much authority as the attribution of poems to Wyat in Egerton. Attributions of poems to Wyatt in sources other than Egerton and Tottel carry much less authority. Finally, and least authoritative, is the location of a poem, in a manuscript other than Egerton, amidst poems for which we have the previously mentioned evidence for Wyatts authorship.

Such sections of poems probably by Wyatt occur in several sixteenth-century manuscript anthologies of poems. While appearance in a group of this kind ordinarily amounts to an attribution of a poem to Wyatt, it does not, in my view, have that character if the poem in question is in the midst of poems attributed to Wyatt in the Egerton MS but is not there or elsewhere attributed to him: presence in a manuscript containing so many poems attributed to Wyatt but absence of attribution of the poem to him anywhere combine, in my view, to suggest that he probably did not write the poem (CLXXVIII is an instance). When we move from external to internal evidence for Wyatts authorship, we must rely on our sense of his attitudes and style, inferred from poems for which there is the kind of external evidence of his authorship described above. This procedure, while legitimate in theory, has in practice usually led modern editors and critics to ascribe to Wyatt every poem that they like from the period. Along with the tendency to ascribe to him most poems in a manuscript that contains some poems attributed to him, this desire to credit Wyatt with good poems has been responsible for swelling the body of works supposedly by Wyatt to its present, rather enormous bulk. In this edition I have divided the poems into two sections: those in Wyatts hand, with revisions in his hand, or attributed to him in the sixteenth century, and those attributed to him after the sixteenth century.

While we do not know with precision the dates in which the manuscripts containing sections of Wyatts poems were compiled, his poems were certainly written in them before 1600. In effect, then, I am distinguishing between poems for which there is external evidence of authorship in the form of Tudor attributions and poems ascribed to Wyatt by modern editors and critics on grounds of attitude, style, or presence in a manuscript that contains poems attributed to him. The different degrees of reliability of the external evidence render impossible any absolute certainty that all the poems in the first section are in fact by Wyatt; and it is indeed possible that some or many of the poems in the second section are his: readers acquainted with Wyatt and the criticism of his poems may well think that CCXI and CCXVI are by him. The second item in the note on each poem presents the external evidence for his authorship, if any; I do not bother to call attention to the absence of such evidence unless the attribution seems particularly far-fetched. Dating the poems is as problematic as establishing authorship. Only a few of the poems can be dated with anything approaching precision and certainty.