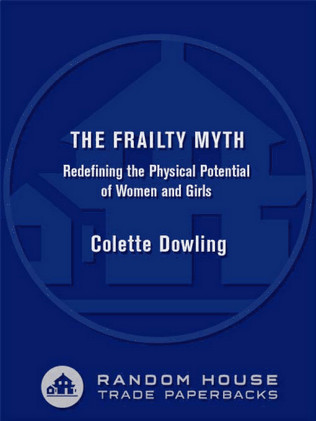

The

Frailty Myth

REDEFINING THE

PHYSICAL POTENTIAL

OF WOMEN AND GIRLS

COLETTE DOWLING

Foreword by Tiffeny Milbrett,

U.S. Womens Soccer Team

Contents

For Rachel, Gabrielle, Conor, and Susan

Acknowledgments

Its always interesting, after finishing a book, to look back and note the many people whose energy and ideas and personal passions have in one way or another contributed to it. Id like to thank my brother, Dr. William Hoppmann, a psychotherapist in Pittsburgh who specializes in EMDR treatment of people suffering from traumaincluding athletes for whom trauma interferes with sports performance. Bill has always been on the cutting edge of his profession, and my discussions with him over the years have had a big influence on my thinking and writing.

My dear friend Dr. Barbara Koltuv read early work on The Frailty Myth and, like a true Jungian, encouraged me to loosen up and fly beyond my sources. I talk about many of my ideas with Barbara and always come away from our conversations enriched.

Val Tekavek, a professor at Bard College, is my writing buddy, the first one Ive ever had, and its been a revelation and a blessing to share my work with her. Val is a wonderful and generous writer and teacher who has helped me enormously in the struggle with themes, and ideas, and the best and simplest ways of talking about them on paper.

I am indebted to many scholars whose research and writing have provided deep background for my own thinking. There are far too many to list here, but I would like to single out a few who, it seems to me, are navigating a sharp course in a new direction. They are sports historian Susan K. Cahn; Patricia Vertinsky in the School of Human Kinetics at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada; Jackie L. Hudson, a movement analyst and teacher of biomechanics at California State UniversityChico (and who lists among her credentials the fact that she taught herself the fallaway jump shot by observing and imitating older players when she was a preteen in Gruver, Texas, but that she was denied the opportunity to compete in youth-league baseball because she was female); and psychiatrist and trauma theorist Judith Herman, M.D., of Harvard Medical School. I found visionary the work of Martha McCaughey, who teaches at Virginia Tech, in developing a theory of what she calls physical feminism. Dr. Barbara Sherwin and Dr. Ethel Siris, a psychologist and an endocrinologist, respectively, have shaped my thinking about the relationship of hormones to physical strength in women.

It was in seeing how different things have been for my two daughters, Gabrielle and Rachel, that I came to recognize my limitations in having been educated before the Title IX amendment to the Civil Rights Act demanded equal rights for women on the playing fields of America. Through their inspiration and encouragement, I have increased the physicality of my own life, and I thank them for helping me to see whats possible for women.

Finally, I thank my agent, Ellen Levine, who has stood behind me for many years, and many books. She thought I would like working with Susanna Porter, my editor at Random House, and she was right. Not only has Susanna paid meticulous attention to the various drafts of my manuscript, she basically required of me a higher level of writing. This book would have been an entirely different one without her help, and I cant thank her enough for her intelligence, her persistence, and her belief in what I was doing.

The Frailty Myth

Foreword

Tiffeny Milbrett

Every year were learning more about what women are capable of, physically. The myths about female weaknessthat our reproductive systems are fragile and dictate that we not be too active, that we have no endurance, that we cant do anything requiring upper-body strengthhave slowly but surely been shot down during the last century.

But that doesnt mean people dont buy into those myths. They do. Girls are still treated differently than boysin the classroom, in the gym, and, eventually, when they grow up, in the boardroom. Theyre not expected to be as competitive. Aggression is frowned upon in girls, yet lots of jobs require a certain amount of aggression. The whole notion of femininitywhich is really just a way of acting and thinking, not some God-given qualityrequires girls to put unhealthy restraints on themselves. It disempowers them. It keeps them from really going for it. When it comes to their bodies, it makes them fear getting too big, or too strong. So they prevent themselves from developing fully. They actually stand in their own way because theyre taught that they should. Whos teaching them? Read The Frailty Myth and find out.

When I was young I didnt really think of myself as a boy or a girl. For as long as I can remember I thought of myself as an athlete. It wasnt that I knew Id grow up to become an athlete; I had no way of knowing that. But I knew I was an athlete as a kid, and it was important to me.

I was seven and a half when I joined my first soccer team. Ive been playing soccer ever since, first in youth leagues, then at the University of Portland, then with the U.S. national womens team. In 1996 we went to the Olympics and won the gold. In 1999, we went to the World Cup and won. In 2000, we went to the Olympics, where we won silver. Now, for the first time, the United States has a professional womens soccer league, the Womens United Soccer Association. There are eight teams in all. I play for the New York Power.

My mother raised me to be an athlete. We lived in Hillsboro, outside Portland, a great area for sports. As a family we were tremendously active, camping, rafting, hiking, skiingyou name it, we did it. My mom, who was a single mother when she raised me and my brother, played on a very competitive soccer team for women over thirty. Every year they went to the state regionals. When I joined the Hillsboro Soccer Club as a little girl, my mom was my first coach.

The only way Ive ever thought about my body is as a source of enjoyment. I wouldnt be where I am today if I didnt enjoy it. I love competing, getting air in my lungs, building muscle, being fit. I love sweating, taking risks, trying to score goals. Never once, growing up, did I experience limitations because I was a girl. Partly, this was due to living in Portland, a city where there are sports opportunitieseven for girlsaround every corner. But it was also because of my mother.

There are two critical things my mother, Elsie Milbrett, did for me. One, she had a completely hands-off approach to my decision making: she let me decide what I wanted to do. Two, she never, ever criticized me, or belittled me, or put me down. She certainly never made me think I had to change my ways or do something in particular because I was a girl. Many times throughout my childhood I was mistaken for a boy. Did this bother her? No. She never tried to change me. She never said to me, Thats not what girls do.

In my neighborhood I played with the boys. I did everything they did, whether it was football, basketball, or building forts. Id come home from school, throw down my books, and run out to play until the sun went down. My mother let me do what made me happy. She didnt worry me by suggesting, Shouldnt you be playing with girls?

Mom, thank you so much for never telling me how I should be.

I know that Ive been fortunate in many ways. Recently, I read Peggy Orensteins Schoolgirls and got steaming mad over the way the girls were treated in the schools she wrote about. I was drawn to The Frailty Myth because it uncovers the physical side of our harmful ideas about girls and women. We need books like this because we need to understand whats going on so we can see and reject what isnt good for us. Its important to stop perpetuating the negative myths that keep us from developing ourselves. Colette Dowling writes about learned weakness in

Next page