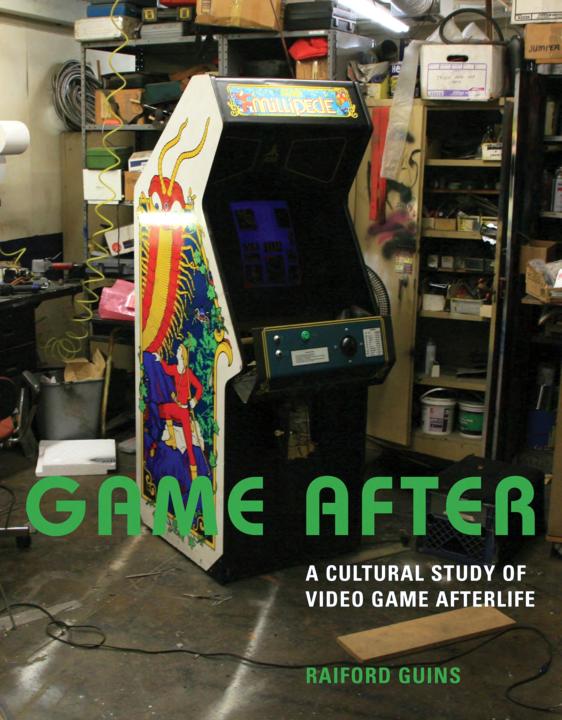

A Cultural Study of Video Game Afterlife

Raiford Guins

America, the land of technology, has many traditions that nostalgically celebrate past technologies. The biggest and loudest is probably NASCAR, which celebrates stock cars outfitted with outdated technologies. For example, overhead valve systems are forbidden, so when Toyota, an outlander, wanted to race, it had to redesign its engines to fit the older technology. Less organized but widespread is the love for Harley Davidson motorcycles' noisy, bulky technologies probably better fitted to the often older and heavier riders who tout them.

In Game After, Raiford Guins, who has founded a game studies collection at Stony Brook University, takes a very up-to-date approach to the cultural afterlife of games. Guins has learned lessons from the last two decades of new social studies of science, technology, and culture. He has taken the "empirical turn," as Hans Achterhuis has claimed for this genre of concrete case studies. In Guins's case it is the material afterlives of video and computer games. He chases his games from California to the Smithsonian.

In his pursuit, he also learns to appreciate what many call the new materialism, and that I call a sensitivity to materiality, now prominent in the humanities and social sciences. This too pervades empirical turn studies and arises out of a shift from early modern distanced observation which spent much of its energy on classifying objects. The new studies have turned to practices-what does one do with (and experience) in an interrelational way with these material machines? Yes, humans make them, but interrelationally, they also make us. Indeed, the omnipresent screen today occupies an average of twelve hours per day for the typical collegian. And the shift to smaller and more mobile screens has also been heavily weighted towards entertainment and game activities. As with all recent technologies there is much and often rapid development. If the early days were dominated by coin-fed arcade games, the newer types are built into portable tablets and mobile phones.

The other emphasis that Guins draws upon in his pursuit is an appreciation for what I call multistability. Unlike the early, often essentialist, philosophy of technology-for example, Heidegger-Guins is appreciative of the multiple contexts and uses of games. If games have become an ever-widening practice and even obsession, there are often unintended side effects. Only gradually have we become aware that the special embodiment skills sharpened in game playing have become part of our contemporary lifeworld. In action, game playing entails learning bodily skills-as does any other physical sport. What was not foreseen was the way in which this leads to a reservoir of pre-skills. Friedrich Kittler cited one such outcome for the late nineteenth century: the invention of the typewriter with its keyboard, he argued, stimulated, within a very few years, the replacement of a dominantly male-gendered secretariat with a dominantly female one. A major factor included the pre-skilling that piano playing fostered among middle class young women, which easily translated into typing skills. Contemporarily, we now have a practice called "Nintendo surgery," the style of surgery utilized in laparoscopy and angioplasty. Seeing and manipulating at a distance calls for precisely the eye-hand coordination developed in video gaming. Or, if one switches to far more distant sensing-manipulating, then robotic warfare and Martian exploration also come to mind. Just this fall my audiologist told me that her husband, an eye and ear surgeon, had given up his practice because the newer "kids" skilled at more robotic techniques could perform better than his now outdated skill level.

Guins is well aware of the multistability of the many points of view available to players, of the multistabilty of through-the-screen worlds of games and of the wide varieties from abstract to three-dimensional beings of games. However, with an informal style that invites us to join him in his gaming road trip, he goes beyond the common player-game interaction to consider a lesser understood mode of interaction: the material lives of games within cultural institutions devoted to their preservation and historical documentation.

Game After is a romp. Its readers will revel over their own memories and uses of games familiar but not disappeared. They are given a sort of second life here, and like the visitors to "The Art of Video Games," the Smithsonian American Art Museum's exhibit that Guins walks through to conclude his book, one ends up as a cheering audience in the midst of games' afterlives.

Don Ihde

Distinguished Professor of Philosophy, Emeritus Stony Brook University

I must start here, with my parents, Al and Nora Guins. They played a cruel trick on me in December 1977. While Christmas shopping at our local Sears in Alexandria, Virginia, I was glued to the playable display for the Atari VCS/Tele-Games System Video Arcade. The display occupied what seemed like hours to my kid mind as my father shopped for more power tools. This thing I clutched and controlled little tanks on is what I wanted, scratch that, what I needed, for Christmas. I already spent a lot of mall time at Time Out arcade as well as at Dart Drug, Safeway, High's, and my local bowling alley to play coin-op games wherever I could find them (I'd even skip school lunch to save quarters). Now with the introduction of game cartridges for home play, nothing else would suffice. Not even Mego superheroes and Mattel Shogun Warriors. We exited the sporting goods/tools section of Sears with a big mystery box. I was ecstatic until my parents broke the news to me: "We can't get you that game system this year 'cause your dad needs new tools!" "Shit, he's already got a basement full!" is what my "dirty-mouth" seven-year-old anger may have breathed beneath fat tears. As it turned out that box wasn't new tools, it was "an Atari" even if the working-class brand said Sears. A cruel trick indeed. Well, Mom, I didn't "stop wasting quarters on those damn machines," and revenge is sweet. Here's payback for all of those quarters stolen over the years.

My acknowledgments could easily read like one of those Bob's Big Boy paper placemats with an idiomatic map of America illustrating numerous points of interest for drivers traveling Interstate highways. Instead of Cadillacs buried in the sand, or the "world's largest thermometer," my map would be plotted with museums, archives, and a barren plot of land in southern New Mexico. On this imaginary map I offer tremendous thanks to the many people I interviewed in the writing of this book. Without their time, willingness to take part in this project, and invaluable insights, I could never have written the book. I mean that sincerely. A huge debt of gratitude goes to Gene Lewin and Morris (Vintage Arcade Superstore, Glendale, California); former mayor of Alamogordo, New Mexico, Donald E.Carroll, and residents of Alamogordo, Ricky and Cathy Jones, Roy Austin, Jason Brockett of KZZX FM 105.3, Kandra Wells of the Alamogordo Daily News, Jeanne Houghtaling and Britney Courtier of the Alamogordo Public Library, and the invaluable Waffle and Pancake Shoppe of Alamogordo; Alison Oswald (Archives Center, Smithsonian National Museum of American History), Joyce Bedi (Senior Historian, Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation), Petrina Foti (Collection Curator, Division of Information Technology & Communications, National Museum of American History), and Nancy L.Card (Assistant Registrar for Acquisitions, Smithsonian National Museum of American History); Jon-Paul C.Dyson (Director, International Center for the History of Electronic Games, Strong National Museum of Play); David Ward (University Library Gaming Initiative, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign) and Jerome P.McDonough (Graduate School of Library and Information Science, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, and Chair of the Preserving Virtual Worlds Project); Zach Vowell (Digital Archivist, UT Videogame Archive, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin), Brenda Gunn (Associate Director of Research and Collections, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin), and Megan Winget (School of Information, University of Texas at Austin); Henry Lowood (Curator for History of Science & Technology Collections and Film & Media Collections, Stephen M.Cabrinety Collection in the History of Microcomputing, Green Library, Stanford University); Paula Jabloner (Director of Collections, Computer History Museum, Mountain View, California), Chris Garcia (Curator, Computer History Museum, Mountain View, California), and Al Kossow (Software Curator, Computer History Museum, Mountain View, California); former Atari employees, Al Alcorn and Steve Bristow; Rochelle Slovin (former Director, Museum of the Moving Image) and Carl Goodman (Director, Museum of the Moving Image); Greg McLemore (International Arcade Museum, Pasadena, California); Van Burnham and Seamus Blackley (The Supercade Collection, Pasadena, California); Gary Vincent and Mike Stulir (American Classic Arcade Museum, Fun Spot, Wiers Beach, New Hampshire); Cliff Spohn (American artist); and Peter Takacs (Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, New York).

![Mark J. P. Wolf (editor) - Encyclopedia of Video Games: The Culture, Technology, and Art of Gaming [3 volumes]](/uploads/posts/book/279290/thumbs/mark-j-p-wolf-editor-encyclopedia-of-video.jpg)

![Ethan Ham [Ethan Ham] - Tabletop Game Design for Video Game Designers](/uploads/posts/book/119417/thumbs/ethan-ham-ethan-ham-tabletop-game-design-for.jpg)