Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

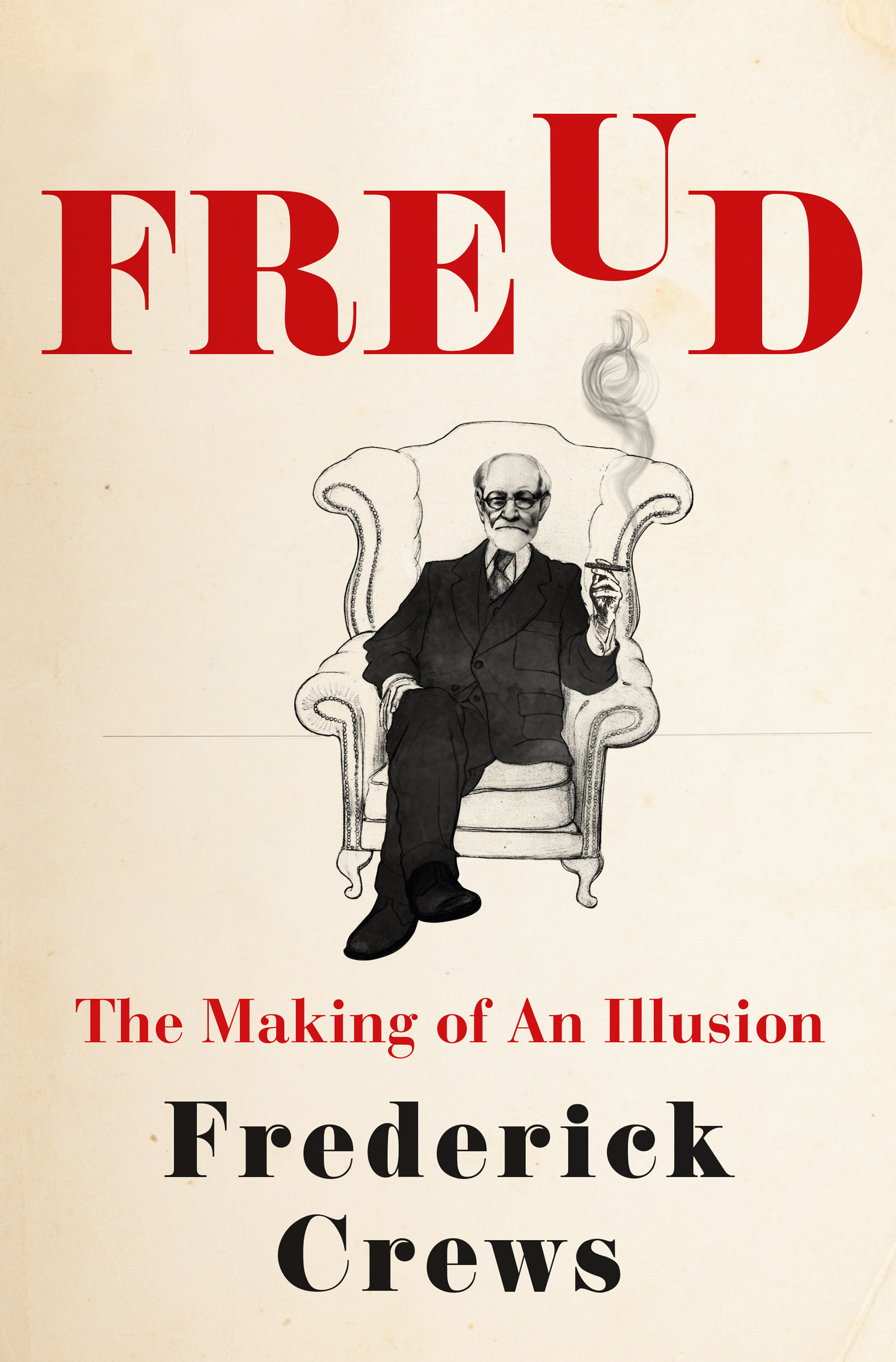

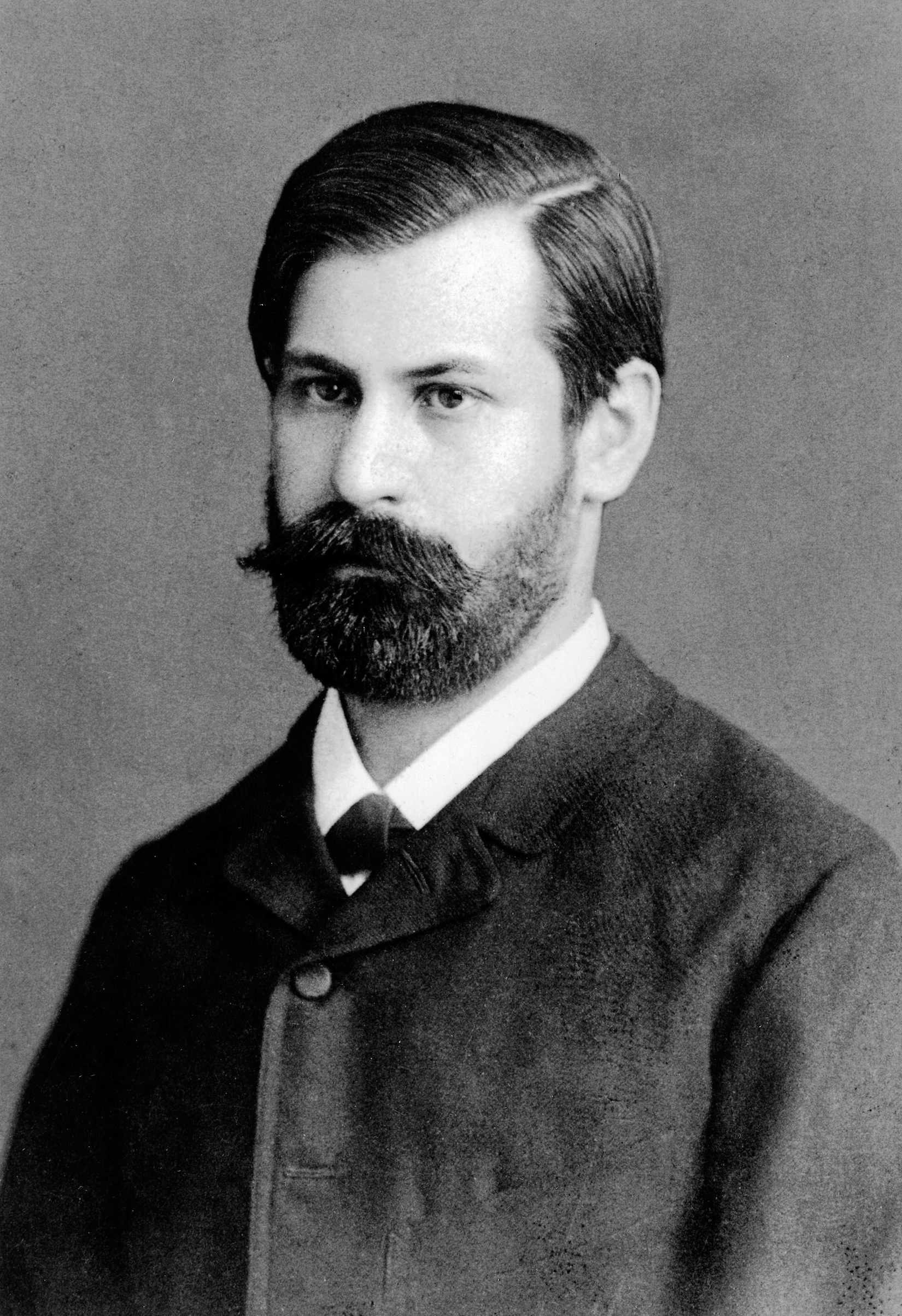

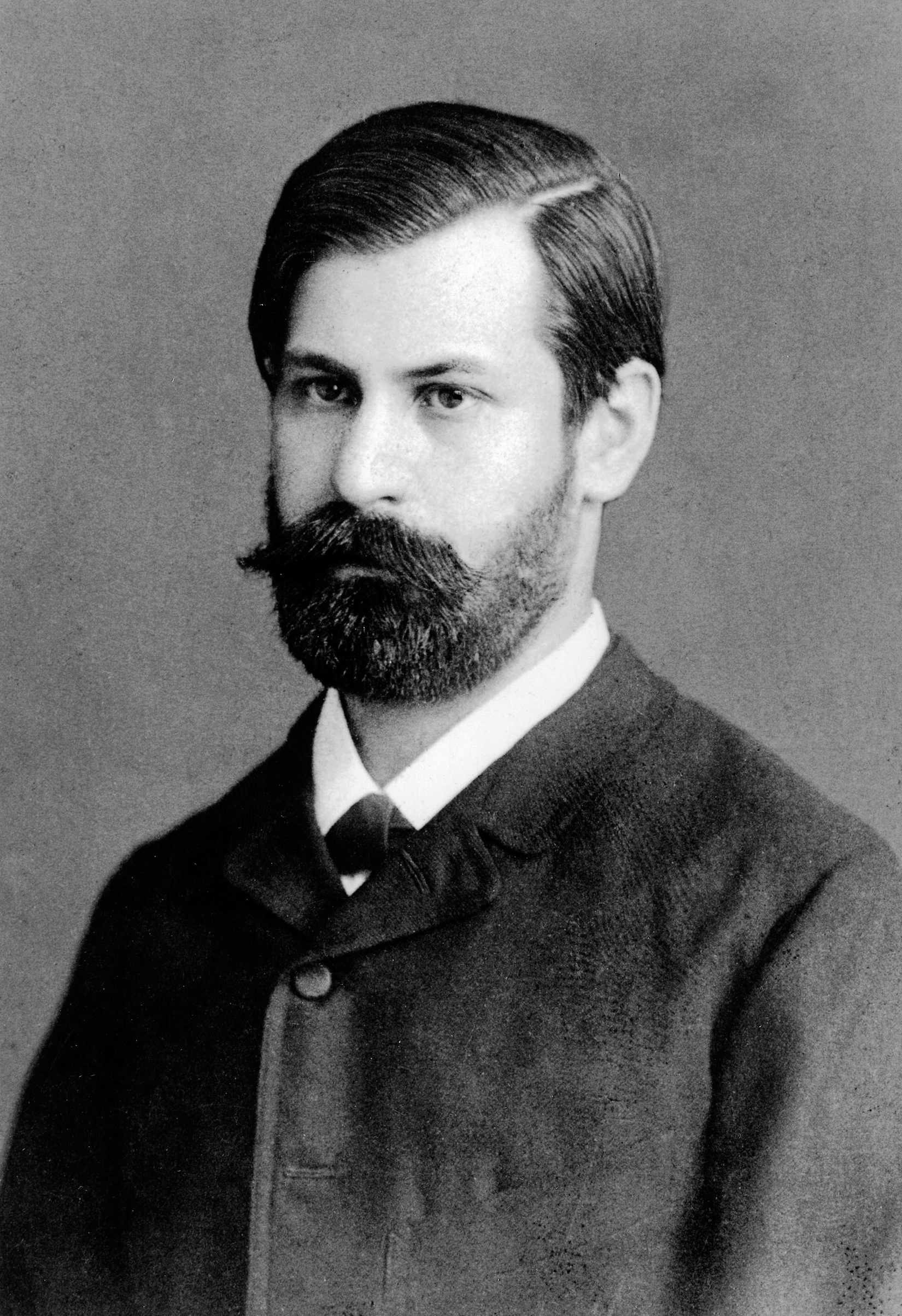

Sigmund Freud, about 1890

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For good friends and Freud scholars:

Malcolm Macmillan , who set the highest standard

Han Israls , who defied the censors

Allen Esterson , who has lived for truth

My largest debt is to Han Israls, both for providing me with vital documents and for posing brave and essential questions about Freuds early career. His groundbreaking 1993 book, Het geval Freud. 1. Scheppingsverhalen , translated into German (1999) and Spanish (2002) but not English, inspired my project.

I have also been sustained and enlightened by exchanges, across many years, with other scholars who have shown us a more human Freud than the fabled one: Jacques Bnesteau, Mikkel Borch-Jacobsen, Maarten Boudry, Louis Breger, Filip Buekens, the late Frank Cioffi, G. William Domhoff, Todd Dufresne, Allen Esterson, John Farrell, Adolf Grnbaum, J. Allan Hobson, Malcolm Macmillan, Peter Rudnytsky, Max Scharnberg, Morton Schatzman, Frank J. Sulloway, Peter J. Swales, Christfried Tgel, Hall Triplett, Alexander Welsh, and Robert Wilcocks.

To readers familiar with the literature, it will be evident that I owe more to Macmillan and Swales, in particular, than any number of citations could convey. I will be pleased if this book whets an appetite for Macmillans great Freud Evaluated and for Swaless incomparable biographical studies, which I continue to urge him to gather between covers. And although Frank Sulloway has justly reconsidered the evaluation of Freuds achievement posed long ago in Freud, Biologist of the Mind , that work has proved to be a treasure chest of important facts and inferences. I have also relied on meticulous research by some authorsmost prominently Albrecht Hirschmllerwhose judgment of Freud and psychoanalysis bears little resemblance to my own.

Special thanks are due Stewart Justman, who patiently read my draft chapters and offered shrewd advice as well as encouragement. I doubt that I could have persevered for eleven years without his expressions of faith in the outcome. Jack Shoemaker, who published my most recent book, has shown me the generosity for which he is well known. It has been a pleasure to work once again with Andrew Franklin, who will be introducing this book to British readers. As always, my most tireless line-by-line critic has also been the nearest and dearest, Elizabeth Crews.

I wrote the manuscript, but it became a book only after receiving the expert shepherding of my agent, Michael Carlisle. Without him, the project would never have come to the notice of Sara Bershtel, the publisher of Metropolitan Books, who saw possibilities where others did not. Sara is also a legendary editorthe best alive, so it is said in New York. In her case, unlike Freuds, the legend has proved to be true. And thanks to her, I was handed along to a truly brilliant copy editor, Prudence Crowther. I am also indebted to Connor Guy for his valuable editorial suggestions and many other services.

For help with (but not responsibility for) my German, I thank Katra Byram, Emily Banwell, Han Israls, and Gerd Busse. And I am grateful for the support of friends, including Joan Acocella, William and JoAn Chace, Karel de Pauw, the late Denis Dutton, Pamela Freyd, Alan Friedman, Jacob Fuchs, E. D. Hirsch Jr., Susan Jacoby, Stephen Kennamer, Emily and William Leider, Jeffrey Meyers, Gary Saul Morson, Paul Nixon, Richard Pollak, Tom Quirk, James Samuels, the late Robert Silvers, James Wallenstein, and my daughters, Gretchen Detre and Ingrid Crews.

However far human beings may reach with their knowledge, however objective they may seem to themselves to be: in the end they carry away nothing but their own biography.

F RIEDRICH N IETZSCHE

Its not a lie if you believe it.

G EORGE C OSTANZA , IN S EINFELD

For an understanding of Freuds pre-psychoanalytic development and his character in general, the most revealing documents are his and Martha Bernayss Brautbriefe , or engagement letters, exchanged between 1882 and 1886. Upon the death of Anna Freud in 1982, the letters were donated to the Freud Archives in the US Library of Congress, where, at her stipulation, they were hidden from view until 2000. That was not an exceptional measure. The first director of the archives, Kurt Eissler, saw to it that other papers would remain unavailable for many more decades, extending as far forward as the year 2113.

Nevertheless, some Brautbriefe have long been familiar, at least in part, to the reading public. Ernst Freud published 97 of them in his 1960 edition of his fathers selected letters, and Ernest Jones quoted or cited more than 200 in his authorized biography. That may sound like a lot, but 1,539 engagement letters of Freuds and Marthas have survived; and not surprisingly, those that fail to tally with his legend have until recently remained either unpublished or redacted.

Recently, however, German transcripts of all of the Brautbriefe have been made available on the Library of Congresss website. Moreover, the full Brautbriefe have begun to be published, in five volumes, by a team of scrupulous German editors. Freud scholarship will be revolutionized when this slow-motion event has concluded. As of this writing, three volumes have appeared, taking the correspondence through September 1884. I have gratefully consulted those texts and the comprehensive notes that accompany them. And, with assistance, I have translated those letters not already published in English.

Because the Library of Congress transcripts contain errors, prudence might dictate that any new study of the early Freud be postponed until all five volumes of the definitive edition have appeared. For me at age eighty-four, however, another prudential consideration takes precedence. I must tell what I know about Freud, hoping that some inevitable mistakes and omissions wont be so grave as to invalidate my inferences.

In quoting published materials that were translated from German, such as James Stracheys Standard Edition of Freuds complete psychological writings, I have occasionally preferred a more literal translation, especially where it makes a substantive difference of meaning. Every such change is indicated in the citation. Paragraph breaks have been inserted into a few lengthy passages.

Finally, readers may wonder why, in the chapters that follow, generic physicians are always he and generic patients are always she . This blunt solution to the always vexing pronoun problem recognizes, but isnt meant to endorse, a historical reality: in Freuds early career nearly all providers of psychotherapy and hypnotism were men, and most of their clients were women.

CP | Sigmund Freud, Cocaine Papers . Ed. Robert Byck. New York: Stonehill, 1974. |

FF | The Complete Letters of Sigmund Freud to Wilhelm Fliess, 18871904. Trans. and ed. Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson. Cambridge, MA: Belknap of Harvard U., 1985. |