ENDING MEDICAL REVRSAL

ENDING MEDICAL REVRSAL

:: Improving Outcomes, Saving Lives

VINAYAK K. PRASAD, MD, MPH

ADAM S. CIFU, MD

Note to the reader: This book is not meant to substitute for medical care, and neither diagnostic decisions nor treatment should be based solely on its contents. Instead, they must be developed in a dialogue between the individual and his or her physician.

Drug dosage: The authors and publisher have made reasonable efforts to determine that the selection of drugs discussed in this text conform to the practices of the general medical community. The medications described do not necessarily have specific approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for use in the diseases for which they are recommended. In view of ongoing research, changes in governmental regulation, and the constant flow of information relating to drug therapy and drug reactions, the reader is urged to check the package insert of each drug for any change in indications and dosage and for warnings and precautions. This is particularly important when the recommended agent is a new and/or infrequently used drug.

2015 Vinayak K. Prasad and Adam S. Cifu

All rights reserved. Published 2015

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Johns Hopkins University Press

2715 North Charles Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363

www.press.jhu.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Prasad, Vinayak K., 1982, author.

Ending medical reversal : improving outcomes, saving lives / Vinayak K. Prasad and Adam S. Cifu.

p. ; cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4214-1772-1 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 1-4214-1772-3 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4214-1773-8 (electronic) ISBN 1-4214-1773-1 (electronic)

I. Cifu, Adam S., author. II. Title.

[DNLM: 1. Delivery of Health Care. 2. Treatment Outcome. 3. Clinical Trials as Topic.

4. Evidence-Based Medicine. 5. Therapeuticstrends. 6. Popular Works. W 84.41]

R733

615.5dc23 2014049513

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Special discounts are available for bulk purchases of this book. For more information, please contact Special Sales at 410-516-6936 or .

Johns Hopkins University Press uses environmentally friendly book materials, including recycled text paper that is composed of at least 30 percent post-consumer waste, whenever possible.

V.K.P. For Mom, Dad, Karthik, and Nancythe four pillars of my life

A.S.C. For Sarah, Ben, and Amelia

CONTENTS

ENDING MEDICAL REVRSAL

INTRODUCTION

THIS BOOK IS ABOUT HOW, despite tremendous advances in the clinical, genomic, and surgical sciences, doctors continue to use medical practices, sometimes for decades, that are later shown to be of no benefit to their patients. Over the past six years, we have researched and struggled with this topic, which we call medical reversal, and in this book we share some of our conclusions.

For those who follow the medical news, the simple fact that medical recommendations change will come as no surprise. Time and again we see enthusiasm for some medical therapy (beta carotene, vitamin E, lowfat diets) rise and fall. First there is certainty that a new practice will help extend your life, then there is equal certainty that it does not. To people outside of medicine (as well as many inside the field), this process is frustrating.

When you look at the day-to-day recommendations that doctors make the ones that usually do not make the newsyou find the story is similar. In one decade, doctors recommend an aggressive treatment of high-dose chemotherapy and stem-cell transplantation for women with breast cancer, promising that it will give a woman her best chance of a cure. Then, over the next decade, doctors report that all of that enthusiasm was misguided; the aggressive treatment was no better than a less aggressive course of therapy, which, incidentally, was what we had been doing previously.

Many people dismiss this phenomenon as the natural course of science: of course hypotheses turn out to be wrong, and we can only move forward through trial and error. Although this is certainly true in biomedical sciencewhere there are false starts, good hypotheses that fail to live up to expectationsit is not the case in medicine. Medicine is the application of science. When a scientific theory is disproved, it should happen in a lab or in the equivalent place in clinical science, the controlled clinical trial. It should not be disproved in the world of clinical medicine, where millions of people may have already been exposed to an ineffective, or perhaps even harmful, treatment.

In this book, we hope to make the case that, when it comes to how we care for people, medicine can do a better job of recommending practices that actually work. In the long run, more and more of what doctors do can be enduring. False starts are inevitable in science, but not when we apply science to caring for people.

HISTORY

We write this book not as critical outsiders, but because, like so many other doctors, we have been there. Each of us recalls moments when we realized that what we had told our patients, or did for them, was wrong: we had promoted an accepted practice that was, at best, ineffective.

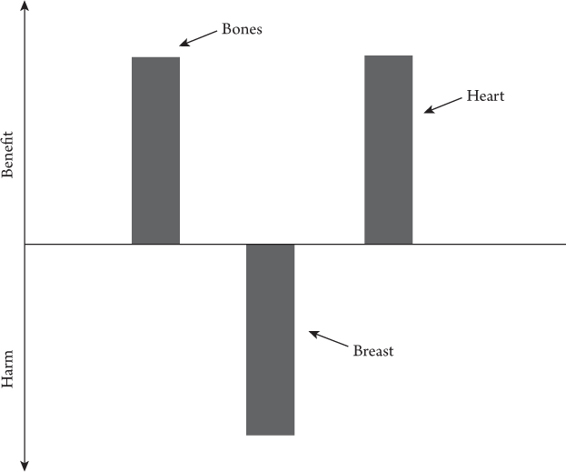

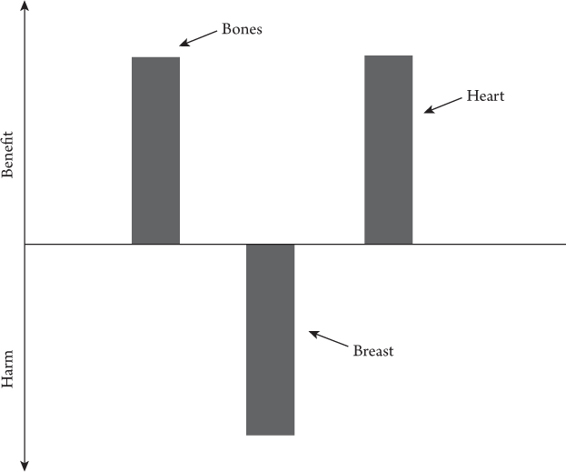

For Adam, like many doctors of his generation, the most memorable reversal was estrogen replacement for postmenopausal women. For years, he would draw the diagram in at least once every couple of weeks. It was a way to explain why doctors recommended that women use estrogen-replacement therapy after menopause. He would explain that the treatment would be good for the bones (decreasing the risk of osteoporosis), bad for the breasts (increasing the risk of breast cancer), and good for the heart (decreasing the risk of heart attacks). On balance, the benefits outweighed the risks. Many of his patients started the therapy.

But then a well-designed clinical trial showed that this diagram was flawed, along with the advice. Estrogen-replacement therapy was of no benefit to the heart. In fact, at least early in the course of therapy, the treatment might even carry some risk. This was a perfect example of reversal. An accepted, widely used therapy was found to be ineffective or possibly harmful. Doctors stopped recommending the therapy not because we discovered something better, but because we never should have used it in the first place.

I.1. Explanation of the risks and benefits of estrogen-replacement therapy (circa 1996).

For Vinayak, the experience with reversal that resonates most occurred in the cardiac intensive care unit (CCU). It was early in his training; the hours were long and the days were grueling. There were orders to be written, tests to coordinate, medications to prescribe, ventilators to adjust, and no shortage of procedures to perform. However, when he went home each day, it was not these things that occupied his thoughts, but whether a core intervention was helping people.

For many of the patients he cared for, the CCU team would recommend placement of a coronary stent, a small, expandable, metal mesh tube that can open narrowed or blocked coronary arteries. The justification for the recommendation varied widely based on the patients problem. For some patients, those having heart attacks, the recommendation was well-founded. Multiple studies had shown that stents saved lives. For other patients the team recommended stents where they had not been proven effective, and in some cases, stents were recommended where they had been shown not to help. For him, the situation became tragic when one patient, who had received a stent she did not need, suffered a complication of the procedure. She experienced harm without possibility of benefit. Vinayak kept thinking, What about our oath to do no harm? Although we preached something called evidence-based medicine, few of us were truly practicing it.

Next page