CONTENTS

Of Cannibals, Kings and Culture:

The Problem of Ethnocentricity Adam Etinson

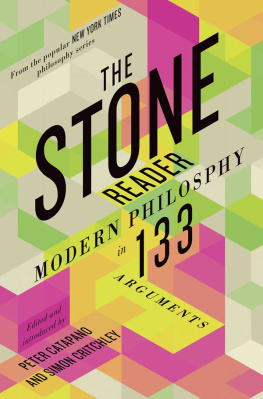

The seventy-seven essays in this volume have been selected from The New York Times philosophy series, The Stone, to represent the best and most accessible writing on ethical questions by philosophers and thinkers working today. The book builds on the popular success of both the Times series, founded in 2010, and the book The Stone Reader: Modern Philosophy in 133 Arguments, published in December 2015 by Liveright.

In putting together this volume we had a primary goal: to create a less expensive, more portable volume than the original Stone Reader, distilled to meet the growing interest in ethics, both in universities and the public sphere. To do this, we didnot simply carve out a subset of the larger anthology, but instead selected the most fitting entries from that book, and updated that grouping with more than thirty newer Stone essays, compiled exclusively for this volume.

The essays here tackle questions of existence, morality, religion, race, family, gender, economics, government and citizenshipnearly every topic of human concernand reflect a range of viewpoints, writing styles and rhetorical strategies. Each one either directly or indirectly raises a question to be explored: Is humanity getting better? Is real inclusiveness possible? How should we respond to evil? Who needs a gun? They sit very comfortably in the tradition of philosophy as a practical tool for the navigation of life, and hence, in this case, under the heading of Modern Ethics.

The key components of the essaysclarity, brevity, integrity and jargon-free languagehave been at the editorial core goal of The Stone since its founding. At their best, these works are useful not only for general readers looking to get beneath the surface of an issue but also for the student or teacher aiming to bring the practices of philosophy and writing together in the project of public engagement. We hope they can and will be read in philosophy courses and seminars, but also at kitchen tables and cafs, in libraries and airports, on road trips and summer vacations.

The Stone, which exists primarily as an entity of the Times opinion section, has become a well-traveled bridge from academia to the public square. It has given professors, scholars and students a vehicle to share their work and views with millions of readers in all walks of life. The conversations typically sparked by these essayswhich appear weekly on the Times website, and occasionally in our national and international print editionsextend over a broad geographical and ideological spectrum, and have given us at least some reason to believe that philosophical thinking is not only not dead, it is a robust, living practice woven into the entire human experience.

The idea of using The Stone in classrooms is not entirely new. Very early on in the project, Simon and I began receiving appreciative notes from teachers using the essays in both high school and university settings, with good results, as well as from students inspired to write essays of their own after engaging with the series. We have also used Stone essays in our own teaching, and have found that the shift that occurs in the educational process is essentially a dynamic one: teaching short, accessible works by living philosophers can foster the sense among students that philosophy is not an esoteric practice to be observed from a distance but a shared activity in a common space, one in which the author of a text may actually be praised, challenged or argued with in person, only a lecture hall or an e-mail away.

It should be noted that Modern Ethics in 77 Arguments is not an ethics reader in the typical academic sense. It does not break down the work into the usual academic divisionsmeta-, normative and applied ethicsbut rather more broadly by topic. Anyone who has compiled a table of contents for an anthology knows that categories, while certainly not useless, are often fluid, and the boundaries they imply often porous. We hope at the very least that those we have provided will help in the navigation of these essays.

As products of a news organization, each Stone piece is a response to the environment. While particular pieces may use important or canonical work in the history of philosophy as a springboard, or to position or fortify an argument, they must by necessity look forward, because the energy that drives this project is a journalistic one. Its reason for being is relevancy. It weds philosophy and journalism in their shared pursuit of, and loyalty to, the truth.

What we hope to have produced is a new text that will be useful both inside and outside the classroomin the academy and on the road, as it were, whether it is the road to enlightenment, or somewhere else entirely.

Peter Catapano,

New York

2017

W HO AMONG US HAS NOT ASKED WHETHER HIS OR HER LIFE IS A meaningful one? Who has not wonderedon a sleepless night, during a long stretch of dull or taxing work, or when a troubled child seems a greater burden than one can bearwhether in the end it all adds up to anything? On this day, too, ten years after the September 11 attacks, when many are steeped in painful reminders of personal loss, it is natural to wonder about the answers.

The philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre thought that without God, our lives are bereft of meaning. He tells us in his essay Existentialism, If God does not exist, we find no values or commands to turn to which legitimize our conduct. So, in the bright realm of values, we have no excuse behind us, nor justification before us. On this view, God gives our lives the values upon which meaning rests. And if God does not exist, as Sartre claims, our lives can have only the meaning we confer upon them.

This seems wrong on two counts. First, why would the existence of God guarantee the meaningfulness of each of our lives? Is a life of unremitting drudgery or unrequited struggle really redeemed if theres a larger plan, one to which we have no access, into which it fits? That would be small compensation for a life that would otherwise feel like a wastea point not lost on thinkers like Karl Marx, who called religion the opium of the people. Moreover, does God actually ground the values by which we live? Do we not, as Plato recognized 2,500 years ago, already have to think of those values as good in order to ascribe them to God?

Second, and more pointedly, must the meaningfulness of our lives depend on the existence of God? Must meaning rely upon articles of faith? Basing lifes meaningfulness on the existence of a deity not only leaves all atheists out of the picture but also leaves different believers out of one anothers picture. What seems called for is an approach to thinking about meaning that can draw us together, one that exists alongside or instead of religious views.

A promising and more inclusive approach is offered by Susan Wolf in her recent and compelling book, Meaning in Life and Why It Matters. A meaningful life, she claims, is distinct from a happy life or a morally good one. In her view, meaning arises when subjective attraction meets objective attractiveness. A meaningful life must, in some sense then, feel worthwhile. The person living the life must be engaged by it. A life of commitment to causes that are generally defined as worthylike feeding and clothing the poor or ministering to the illbut that do not move the person participating in them will lack meaningfulness in this sense. However, for a life to be meaningful, it must also be worthwhile. Engagement in a life of tiddlywinks does not rise to the level of a meaningful life, no matter how gripped one might be by the game.

Next page