Re-edited from HTML copy for ebook format by Jerry Abbott, formerly editor for National Vanguard Books (1999-2003). This work was done as a gratuity in my retirement, as a further keeping of my promise to Dr. William L. Pierce, which is the echo of his promise to William G. Simpson that this book would be republished. This edition was edited with Sigil (v. 0.7.4) for epub format on 20 January 2014. It was converted to mobi format with Calibre (v 1.20).

To My Reader ..

You may find in this book ideas or ideals that at first hearing strike you as abhorrent. They may clash with what you have long believed to represent the highest in human experience, or cherish as too holy to be questioned. Or you may find yourself chilled by conclusions that I reach or remedies that I press that you think too drastic. But I would remind you that the disintegration of our whole society is far advanced, that the time allowed us for action is short, and that the peril hanging over us is fearsome. Extreme emergencies may require extreme measures. Our need is for men of the courage and independence of mind to set aside all taboos, men who will search and reassess the entire experience of our people with discernment and with insight, and will then have the resolution and the dedication to apply to the solution of our problems all the light and the fullest wisdom to which their search has led them even though it cost them their lives.

And one word more.

In general there is much in each chapter that, if it is to be rightly understood and its spirit fully sensed, must be read in the light of all that has gone before. Therefore, I would urge my reader to avoid skipping around. The reading will surely prove the most fruitful if he begins at the beginning and reads straight through.

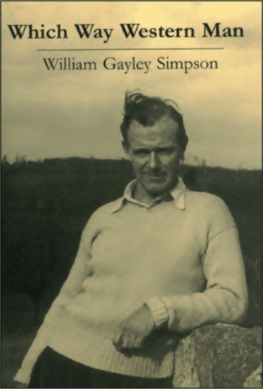

William G. Simpson

Foreword

Between the covers of this book the world of the West is quietly weighed in the balance, and at many critical points found wanting. As long ago as 1920, I perceived that Western civilization was dying, as Rome was dying at the height of her Empire, and as many another civilization has died. In time I came to see that we people of the West were sick not only in the outward conditions of our social and political life, not only in the decay of our character, in the decline of our intelligence, and in our loss of the control of our destiny, but in many respects in the very values and ideals on which we prided ourselves, by which we long shaped our course and thought to maintain our greatness.

As it happened, it was out of the throes of my own personal experience that I first came to suspect the soundness of some parts of our tradition, which for centuries had been most hallowed and most decisive in our historical development. The experience was quite exceptional and exceedingly searching. In 1920, after five years of relentless questing for the place in our world where I might make my life count for the most, I committed myself without any reserve and without compromise to a course dictated to me by the furthest reaches of my religious insight and devotion, my highest idealism, and my most thoroughly thought-out convictions. With whole-souled abandon, I gave myself over to an effort to put the teaching of Jesus into practice. I took him at his wordwith absolute literalnessin the same sense that Francis of Assisi did. The story of this is not to be told here, though bits of it will crop out now and then in my pages to follow. For the present, suffice to say that the undertaking proved to be spiritually arduous in the extreme, as only those can appreciate who comprehend how austere Jesus real teaching was. Its requirements tested all I had in me. After nine years of such experience, I came to a dead end. I was left in a state of exhaustion and with a profound suspicion that something was wrong. But the experience of those nine years did more than test me: it tested no less all the foundations I had looked to when I decided on my venture, and which alone and throughout had sustained memy ardent Christianity, my starry-eyed idealism, and my liberal philosophy.

The breakdown of my venture threw me into spiritual and intellectual chaos: for years afterwards, I did not know what I believed about anything. I found myself compelled to make ruthless investigation of all my underpinning. Before I was through, many of the fundamentals of our Western White mans heritage of wisdom, together with much critically important evidence brought forth by modern scientific investigation, had to pass through the crucible of my relentless search for truth. And my steady reading of Nietzsche blew this to a white heat. This search has lasted ever since, and it will go on as long as I live. It has been absolutely free. No one has paid me for it, and there has been no one to stop me. I soon provided myself with economic independence, largely by the work of my hands. For forty years the best of my free time has gone into this quest. I have ransacked heaven and Earth for honest answers to my questions. Nothing has been taboo. No doors were closed. I could draw any conclusions the evidence seemed to support and to call for. And I was free to say what I thought. For my own very existencefor the very ability to live with any vital meaning and with any deep peace of mindthis was an ineluctable necessity.

I knew full well that I was no specialist, and I was soon to be told that in this specialist age no mannot even any scientist, let alone any laymancould make a synthesis, even of scientific findings, which anyone would consider significant; and that any attempt to cull, not only from science but from religion and history as well, the materials for shaping a wisdom about life would be as foolish as it would be impossible. Of course, to my way of thinking, unless each of the more important specialisms does, sooner or later, render up its meaning for human life, and unless all of these are gathered together to form a wisdom about how man must live if ever he is to come to his fulfillment, science is ultimately useless and must at last be cashiered. But in any case, at the time, I was very little concerned about gaining anyones attention or with what the professors might say by way of deprecation. I was too much like a man who has been thrown overboard in mid-ocean: I must find something to sustain me or I should drown. As against this, nothing else mattered. Let people think about me what they liked: before I could ever again know where I was in the universe, I must find ground that I had reason to believe I could stand on, ground that I was sure would support me. Only then could I hold myself together, get my bearings, know in what direction to head, where to draw lines, with whom to take my stand, who were my friends and who my foes. In short, only on this condition could I live. And it was some fifteen years of such research, experience, and reflection that finally resulted in the original manuscript of this book.

As my struggle moved on toward certainty and peace of mind, it began to come to me more and more that, after all, in an age of disintegration and dissolution like ours, when, from one quarter or another, all standards and all values are being not only challenged but rejected, when the old moorings to tie to are being washed away and the stars that for centuries men steered by are falling from our sky, there must be a multitude of other men who are feeling a desperate need of some tested certainties to hold to and to live by. Some of them, in particular, might take great heart to learn of one whose primary concern was with nothing so tawdry as mere human survival, but who on the contrary was concerned above all else with quality in human life, who longed and struggled everlastingly that Man, and especially his own kind, his own race, those with whom he felt the deepest affinity and for whom he recognized his greatest responsibilityshould not only go on but go up.