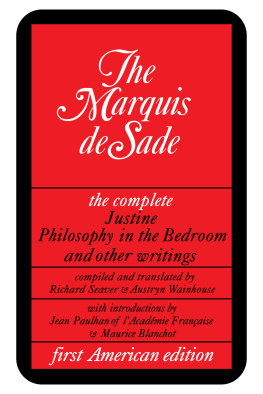

Justine, Philosophy in the Bedroom, and other writings

THE MARQUIS DE SADE

COMPILED AND TRANSLATED BY

RICHARD SEAVER & AUSTRYN WAINHOUSE

WITH INTRODUCTIONS BY

JEAN PAULHAN OF L'ACADMIE FRANAISE & MAURICE BLANCHOT

Copyright 1965 by Richard Seaver and Austryn Wainhouse

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, or the facilitation thereof, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Any members of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or publishers who would like to obtain permission to include the work in an anthology, should send their inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003.

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Distributed by Publishers Group West

www.groveatlantic.com

Acknowledgments

The essay by Jean Paulhan, The Marquis de Sade and His Accomplice, was originally published as a preface to the second edition of Les Infortunes de la Vertu published in 1946 by Les ditions du Point du Jour, copyright 1946 by Jean Paulhan. The essay was later reprinted, under the title La Douteuse Justine ou les Revanches de la Vertu, as an introduction to the 1959 edition of Les Infortunes de la Vertu published by Jean-Jacques Pauvert. It is here reprinted by permission of the author. The essay Sade by Maurice Blanchot forms part of that authors volume entitled Lautramont et Sade, copyright 1949 by Les ditions de Minuit, and is here reprinted by permission of the publisher. The editors wish to thank Grove Press, Inc. for permission to include certain information in the Chronology in the form of both entries and notes, taken from The Marquis de Sade, a Definitive Biography, by Gilbert Lely, copyright 1961 by Elek Books Limited. This work is a one-volume abridgment of the two-volume La Vie du Marquis de Sade by the same author, to which the editors have referred in their Foreword, wherein further acknowledgments have also been made. Finally, the editors wish especially to thank Miss Marilynn Meeker for the meticulous job of editing, and for the number and diversity of her suggestions.

My manner of thinking, so you say, cannot be approved. Do you suppose I care? A poor fool indeed is he who adopts a manner of thinking for others! My manner of thinking stems straight from my considered reflections; it holds with my existence, with the way I am made. It is not in my power to alter it; and were it, Id not do so. This manner of thinking you find fault with is my sole consolation in life; it alleviates all my sufferings in prison, it composes all my pleasures in the world outside, it is dearer to me than life itself. Not my manner of thinking but the manner of thinking of others has been the source of my unhappiness. The reasoning man who scorns the prejudices of simpletons necessarily becomes the enemy of simpletons; he must expect as much, and laugh at the inevitable. A traveler journeys along a fine road. It has been strewn with traps. He falls into one. Do you say it is the travelers fault, or that of the scoundrel who lays the traps? If then, as you tell me, they are willing to restore my liberty if I am willing to pay for it by the sacrifice of my principles or my tastes, we may bid one another an eternal adieu, for rather than part with those, I would sacrifice a thousand lives and a thousand liberties, if I had them. These principles and these tastes, I am their fanatic adherent; and fanaticism in me is the product of the persecutions I have endured from my tyrants. The longer they continue their vexations, the deeper they root my principles in my heart, and I openly declare that no one need ever talk to me of liberty if it is offered to me only in return for their destruction.

THE MARQUIS DE SADE, IN A LETTER TO HIS WIFE

Foreword

That the Marquis de Sade also wrote books is a fact now known to almost everyone who reads. And knowledge of Sade as a writer ordinarily ends there. For of his immense and incomparable literary achievement, and of his capital importance in the history of ideas, hardly a suspicion has been conveyed by occasional collections of anodyne fragments culled from his writings or by more frequent and flagrantly spurious adaptations. (Of the two, cheap-paperback pastiche and more tastefully contrived anthology of excerpts, the latter, equally meretricious, is hardly the less dishonest.) To date, this is Sade bibliography in the United States. To date, Sade remains an unknown author.

For this, censorship, Puritan morality, hypocrisy, and lack of cultivation may be blamed, although not very usefully, since Sade sought condemnation. Ultimately, the fault for it is all his own, and the fate of his books is his triumph. Strange? To be and to stay an unknown author, that has always been his status and his destiny, that was the status he coveted, that was the destiny he created for himself, not by accident or unwittingly, but deliberately and out of an uncommon perversity. To write, but to go unreadthis has happened to many writers. To write endlessly and under the most unfavorable conditions and as though nothing mattered more than to write, but to write in such a way, at such length, upon such subjects, in such a manner and using such language as to render oneself unapproachable, unpublishable, unknown, and yet upon succeeding generations to exert the most intense and enduring influencethis, it will be admitted, is rare indeed.

Secrets cannot survive their disclosure; to bare Sade to the public would seem to be rendering him a disservice. Against this betrayala graver one by far than any accomplished by the obscure tradesmen who from time to time get out a childs version of JustineSade has a defense: it consists in maintaining the reader at a distance, not merely at arms length but at a remove one is tempted to call absolute. Or, to put it more simply, in forcing every readerevery so-called reasonable readerto reject him.

Thus, the present attemptwhich is the first to be made in the United Statesto provide the basis for a serious understanding of Sade is in a certain sense bound to fail. In this sense: the reasonable man (we repeat) can come to no understanding with this exceptional man who rejects everything by which and for which the former liveslaws, beliefs, duties, fears, God, country, family, fellowseverything and the human condition itself, and proposes instead a way of life which is the undoing of common sense and all its works, and which from the point of view of common sense resembles nothing so much as death; and which is, of course, impossible. Such must be the judgment of the reasonable manof him who builds, saves, increases, continues, and thanks to whom the world goes round.

Even so, however firmly he be established in the normality that makes everyday life possible, still more firmly established in him and infinitely more deeplyin the farther reaches of his inalienable self, in his instincts, his dreams, his incoercible desiresthe impossible dwells, a sovereign in hiding. What Sade has to say to usand what we as normal social beings cannot heed or even hearalready exists within us, like a resonance, a forgotten truth, or like the divine promise whose fulfillment is finally the most solemn concern of our human existence.

Whether or not it is dangerous to read Sade is a question that easily becomes lost in a multitude of others and has never been settled except by those whose arguments are rooted in the conviction that reading leads to trouble. So it does; so it must, for reading leads nowhere but to questions. If books are to be burned, Sades certainly must be burned along with the rest. But if, ultimately, freedom has any meaning, any meaning profounder than the facile utterances that fill our speeches and litter the columns of our periodicals, then, we submit, they should not. At any rate, it is not our intention to enter any special plea for Sade. Nor to apologize for one of our civilizations treasures. Disinterred or left underground, Sade neither gains nor loses. While for us... the worst poverty may be said to consist in the ignorance of ones riches.