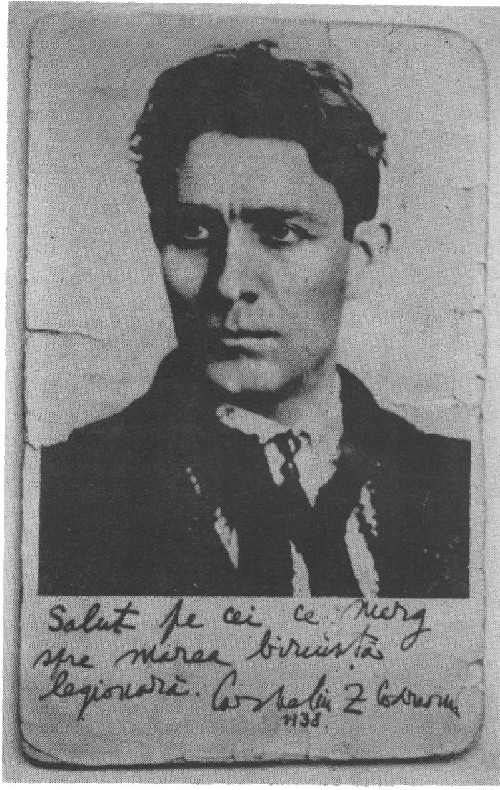

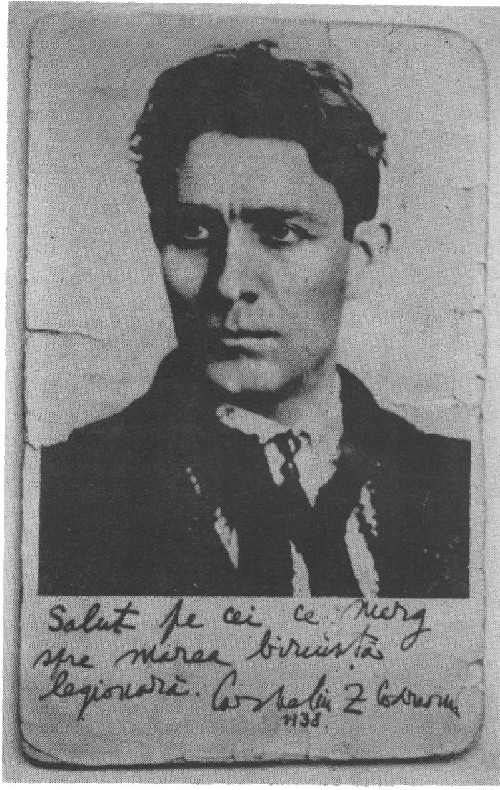

CORNELIU ZELEA CODREANU

FOR MY LEGIONARIES

(THE IRON GUARD)

(I greet those who march toward the great legionary victory.

Corneliu Z. Codreanu 1938)

FOREWORD

A dominant feeling overwhelms me, now that the responsibility of inditing these lines is mineit is one of overpowering and pervasive humility. I fear lest the historical and spiritual greatness of the author of this work fatally lead me into vainglory, simply because I was his contemporary and knew him, and thus enjoyed the privilege of admiring his ascendancy, of hearing his opinions, of obeying hisorders, and of dedicating myself with all my heart to the aims he proposed.

Nothing more clearly characterizes the fascination which the Captain (As the legionaries affectionately dubbed their leader, Corneliu Zelea Codreanu) exerted upon those who followed him than the testimony of one of the most distinguished and renowned Romanian scholars, Professor Nae Ionescu of the University of Bucharest: If the Legions chief told me to take a small box and a bootblacks stool,and set up shop before the Royal Palace to shine the shoes of passersby, I would do it, being fully convinced he had reasons for his order. I remember that another professor, he who succeeded the eminent historian A.D. Xenopol at the University of lasi, remarked around 1937 that Codreanus authority, which inspired Romanian students to follow him, was much greater than that enjoyed by all the professors of all our universities put together.

Indeed, the Captain was the national pedagogue of Romania between the two world wars!

Codreanu in a very short time won similar influence over all the other classes of society. When the Kremlins Bolshevism, thrust by the Red hordes from the Russian steppes toward the civilized West, invaded Romania by force of arms following August 23, 1944, it found among the twenty million inhabitants fewer than a thousand Communists to be entrusted with the Satanization of our country. The workers corps, founded as part of the Legionary Movement in the 30s, dammed in the nick of time the Marxist flood, which would otherwise have submerged Romania and gone on to inundatemuch of the rest of Europe.

Naturally, the Legionary Movement first recruited university students, but the next highest priority was given to enlisting and re-forming workmen. Soon after the Bolshevik conquest of Russia in 1917, the Muscovite beast began to bare its fangs in Romania: agitation and disorders were fomented in Moldavia by agents infiltrated from Galicia, and by their shabbas goyim to such an extent that the young student, Codreanu, began his nationalist campaign in Iasi against overwhelming numbers: he alone faced 5000 communist workers who had occupied the Nicolina railway works; he climbed to the roof of the main building, jerked out the red flag and triumphantly planted there the Romanian tricolor.

It so happened that I was perhaps the first and most constant eyewitness of the beginnings of Codreanist confrontations within the workers groups in Iasi. When Codreanu first got in touch with the patriot Constantin Pancu, who is mentioned in the first pages of this book, it was on a Thursday in November 1919. He found in the hall where the Guard of National Conscience usually met, only one student among those present. He was the one who occasionally contributed articles to the Guards paper under the name of Dimga, an abbreviation of the name affixed today at the end of this foreword. Years later, after the formation of the Legionary Workers Corps (Oct 25, 1936) under the command of Engineer Gh. Clime, the Captain suggested that the Legionary Movement unite intellectuals and workers in a common effort and proposed that I take upon myself a dual leadership: that of the intellectuals and of the workers (the latter to be shared with Clime) in Moldavias capital. In the message addressed to me, brought by Clime himself, mention was made of the pride that the legionary workers of Iasi would feel at having a university professor as their leader, whilst the bewildered workers were toeing the line for such Jewish clowns as Gheler and Ghelerter.

It was also at the Captains behest that the two great artistic talents of the Legionary Movement, Radu Gyr, the poet, and Nelu Manzatu, the musician, composed the hymn of the legionary workers:

...From heavy, hard hammer strokes,

Bent over by hunger and want,

From slag of furnace and of boilers,

Hungry we raise ourselves, and naked...

...From lightning we will build a new country

On great anvils over the centuries

From sacrifices and from hammer blows

We will forge for ourselves a destiny of iron...

The purveyors of public opinion denounced the organization founded by the Captain as an imitation, an offshoot, of Fascism and Nazism.

During one of my conversations with Corneliu Codreanu as I stopped over in Bucharest on my way to Italy, he expressed the opinion that my experience as a participant in the Carmen Sylva work camp would be more beneficial than another trip to Rome, and he revealed to me that if nations are to be reborn, they must start with their own innate qualities and their ancestral outlook on life. The Fascists, as descendants of the ancient Romans, who were the creators of the Law and of an unsurpassed state organization, naturally had the ideals of the Roman magistrates, and necessarily gave attention to the formal juridical aspect, so that they were like individuals who first of all take care to clothe their bodies, while the Germans, deeming themselves the most authentic representatives of the ancient Indo-Germans and admirers of racial purity, gave special attention to the blood, namely to the biological element. We, descendants of Latin stock grafted onto a Thracian trunk, were prevented by history and by time from carving out for ourselves an early state, with the result that our concept of legislation per se was limited to religious precepts, the laws of Christian morality constituting the law of our land in its entirety, so that we Romanians were preoccupied with the soul. That is why the school of the nest aims to transform the legionary into a new man. Thus our legionaries have a self control more effective than the discipline found in any other European political movement. When a legionary initiates an action, he does not do so with the idea that it will benefit him or his family; his purpose is to serve the Legion, and even so, he will avoid acts that could harm the Nation. Having learned from the Captain that the final aim of the Nation is not mere existence but spiritual life, he keeps himself in hand at all times with the brake of Christian morality. It has been rightly stated that the Legionary Movement was not a simple political organization, but also a military and religious order.

The murder of Codreanu did not end his work, but, as did Golgotha for Christians, projected it for other peoples and into other times. He was not merely a genial exponent of the aspirations of his generation: he formulated ideals valid for all future generations. He traced out the only firebreak by which the Marxist conflagration can be contained. The tranquility of peaceful and balanced living will not be attained in todays ever - restless world except by the way preconized by him, namely by the road of peoples return to God. That is why level-headed youth in several parts of the convulsed globe are now being guided more and more by the doctrine of the movement ideated by Codreanu. The most telling demonstration of this is the recent recognition of it by healthy-minded youth in Chile, whose spokesman, an eminent university professor, clearly declares that the anti-communist victory there has initiated posthumous victories for Comeliu Codreanu.