PRAISE FOR JEFFS PREVIOUS BOOKS

Teaming with Microbes

Will help everyone create rich, nurturing, living soilfrom organic gardening devotees to weekend gardeners.

Michigan Gardener

Should be required reading for everyone lucky enough to own a piece of land.

Seattle Post-Intelligencer

A breakthrough book for the field of organic gardening... No comprehensive horticultural library should be without it.

American Gardener

This intense little book may well change the way you garden.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Sure to gain that well-thumbed look that any good garden book acquires as it is referred to repeatedly over the years.

Pacific Horticulture

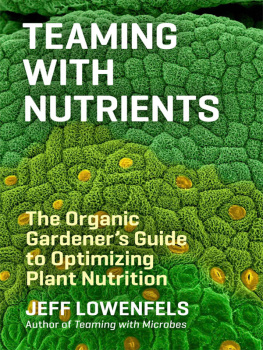

Teaming With Nutrients

If you really want to get a sense of how little we know about how plants use fertilizersand I count myself in this leagueyou should read Lowenfels latest book, Teaming With Nutrients, which gets deep into the weeds, so to speak, of the microscopic architecture of plants and the biochemical processes at play... Suffice to say, Lowenfels is a man who knows his anions.

Washington Post

Your awe of plants and the lives they lead will increase if you just read it, and youll never garden the same old way again.

Muskogee Phoenix

Colorful illustrations, plentiful and readable diagrams, and a well-executed chapter structure make this an indispensable resource.

Publishers Weekly

Offers a crash course in discovering soil structure, fertility, and microbial actions.

Palm Springs Desert Sun

Lowenfels offers a deeper understanding of the major and minor plant nutrients and delivers the necessary science in a conversational style that most gardeners will appreciate.

Monterey County Herald

TEAMING

WITH

FUNGI

The Organic

Growers Guide to

Mycorrhizae

JEFF LOWENFELS

TIMBER PRESS

Portland, Oregon

For Lisa, David, Madelyn, and Miles, the next generation of gardeners.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

A STAGGERING 80 TO 95 percent of all terrestrial plants form symbiotic relationships with mycorrhizal fungi. In these relationships, or mycorrhizae (mycorrhiza, singular), the host plants supply the mycorrhizal fungi carbon, and in return, the fungi help roots obtain and absorb water and nutrients that the plants require. These relationships are vital to the health of almost all plants that grow on Earth. Each group of mycorrhizal fungi interacts and colonizes its plant host in a different way, in a process so complicated that it took scientists a long time to catch on to its importance.

If you are reading this book, you are probably familiar with the soil food web, the incredibly diverse community of organisms that inhabit the soil. Most of you understand the importance of symbiotic (mutually beneficial) relationships among plant roots and a multitude of soil organisms. You are aware of the relationships among bacteria, rhizobia, and legume plant roots that result in nitrogen fixation, and you understand that bacteria can form a symbiotic relationship with plant roots. Soil-borne mycorrhizal fungi, the subject of this book, interact with plant roots in a similar way.

Mycorrhizae have been known since 1885, when German scientist Albert Bernhard Frank compared pine trees grown in sterilized soil to those grown in soil inoculated with forest fungi. The seedlings in the inoculated soil grew faster and much larger than those in the sterilized soil. Nevertheless, not so long ago (in the 1990s), the importance of mycorrhizal fungi was unknown to many farmers and gardenersand most garden writers. We feared and loathed all fungi, the stuff of mildews and wilts. Fungi were usually considered downright evil, and most of us took a one-size-fits-all fungicidal approach in our gardens. I had been writing a weekly garden column for some 25 years when I first heard the words mycorrhizal and mycorrhizae in 1995. I was embarrassed by my lack of knowledge of these important organisms, but when I asked my peers if they had ever heard of mycorrhizal fungi, they had no idea what I was talking about. (When I first started writing about mycorrhizae, not only did my word processor programs spell checker reject the word, but my editor did as well.)

WHY MYCORRHIZAE MATTER

Truth is, almost every plant in a garden, grown on a farm or orchard, or living in a forest, meadow, jungle, or desert forms a relationship with mycorrhizal fungi. In fact, many plants would probably not exist without their fungal partners.

It is now readily acknowledged that mycorrhizal fungi are important to agriculture, horticulture, silviculture (the practice of growing forests), and even hydroponics (in which plants are grown in water, without soil). Mycorrhizal fungi play a growing role in feeding the world. The benefits that plants derive from mycorrhizal fungi include increased uptake of nutrients, increased resistance to drought, increased resistance to root pathogens, earlier fruiting, and bigger fruits and plants. They are helping farmers better withstand drought and use less fertilizer, particularly phosphorus, because mycorrhizal fungi find and restore phosphorus in the soil, making it available to plant roots. Mycorrhizal fungi are also being used to remediate and reclaim spoiled land and to prevent erosion of valuable soils.

MYCORRHIZAL MYTHS

Mycorrhizal fungi are difficult to grow in a laboratory environment, and most are visible only with a microscope, so for a long time it was not easy for scientists to identify and study them. Before we understood much about mycorrhizal fungi (many mycologists originally thought they were pathogenic), only a small, dedicated group of scientists studied them. Even when they could be grown in a lab, these fungi didnt always behave as they would in an outdoor field study. It took a while to develop replication methods and to understand the conditions necessary for successful establishment of mycorrhizae. As a result, a lot of myths developed. This book aims to dispel many of these.

First, there is a presumption that mycorrhizal fungi are ubiquitous, so we do not need to add them to the soil. But considering that most of the soil around homes is not native, but has been brought in from somewhere else, it may not include the fungi your plants need. In addition, you may not have been treating your soil, and therefore its mycorrhizal fungi, in a way that benefits the fungi. Moreover, mycorrhizal fungi are competing with the native microorganisms in the soil, and populations of the fungi can be insufficient and far below those included in a commercial or homemade inoculum.

Next, some erroneously believe that although hundreds of native fungi can exist within soils, only a handful of these are available in commercial mixes, so they could not possibly be effective. Although these mixes contain only the most promiscuous of the mycorrhizal fungi, they are likely to colonize your plants even more so than any native fungi in your soil.

And, finally, there is the myth that plants inoculated with mycorrhizal fungi do not grow any larger or healthier than those to which no fungi have been applied. As you will learn in this book, this is often because the gardener makes mistakes, such as adding rich fertilizers that can disrupt or destroy the fungi, or otherwise mistreats the mycorrhizal fungi population. In addition, the benefits conferred by mycorrhizal fungi often have nothing to do with visible plant growth.