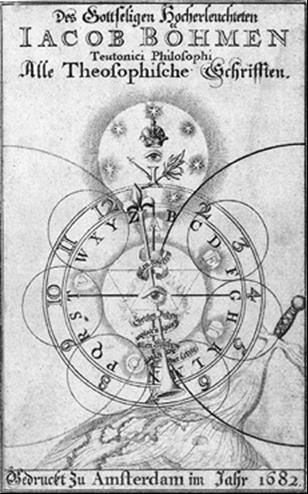

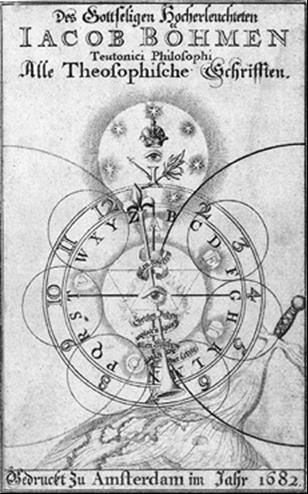

SCIENCE, MEANING & EVOLUTION:

THE COSMOLOGY OF JACOB BOEHME

By Basarab Nicolescu

Foreword by Joscelyn Godwin

Afterword by Antoine Faivre

Translated from the French by Rob Baker

CopyrightBasarab Nicolescu 2013

Jacob Boehme Online

FOREWORD

SINCE this is a book about the union of opposites and the reconciliation of contraries, it will

probably appeal to two distinct types of readers. First, there will be those who suspect that modern

science may be teetering on the edge of an abyss of discovery as formidable as the Copernican

Revolution. To them this Foreword is addressed. Second, there are those already familiar with

Jacob Boehme or with Western esotericism, who feel that their philosophic studies cannot be

isolated from the scientific problems of today. Antoine Faivres Afterword will speak to that

constituency.

What common ground could possibly serve for a conversation between Basarab Nicolescu, a

modern physicist, and Jacob Boehme, a Renaissance visionary? To most people science is fact,

imagination is fiction, and that is the end of the matter. Yet this very split, which was opening in

Boehmes century and which may begin to close in our own, is the symptom of a perilous

disharmony in our inner and outer worlds. Several decades ago there was a noisy debate, opened by

the British scientist C.P. (later Lord) Snow, who was also a popular novelist, concerning what he

called the Two Cultures." Snow warned that the scientific and the humanistic communities were

growing further and further apart, to the degree that a member of one culture was not only

incapable of understanding the language and interests of the other, but did not even value them. The

scientists had become enmeshed in a world of technology and quantitative thinking, to which the

qualitative world of arts and letters, philosophy, and religion was at best a pleasant garnish; while

the humanists were quite content to be mathematically and scientifically illiterate, secure in the

superiority of their pursuits to dirty jobs like engineering. Snow left his audience in no doubt about

the potential danger of such a cleavage.

If there has been any improvement in the situation since those early 1960s, it is probably thanks to

the scientists, and especially to physicists, many of whom have been driven by the discoveries of

this century to become metaphysicists. There is a certain hierarchy among scientists, in the sense

that the principles on which one science is based serve another as materials for study. Engineers and

other technicians do not need to argue about the principles handed to them by the theoretical

sciences, such as biology, chemistry, and physics. Biologists, generally speaking, rely on the laws

of chemistry, while chemists take for granted the principles of physics. Yet the chemists useful

models of atomic structure are fictions to the contemporary physicist. Can one go a stage further,

and say that the principles taken for granted by the physicist are studied by the metaphysicist? In

some circles, one might be forgiven for such talk, since at its highest and most speculative levels,

physics now investigates what is beyond (meta) the physical world, and treats with what surprise

at its own audacity! the very questions of being and non-being that were once reserved for

philosophers.

Humanists might object to the idea of a parallel hierarchy being drawn among their own disciplines,

unless they remember that Theology was traditionally regarded as reigning like a queen over the

Liberal Arts, the latter being based on human investigation rather than on divine revelation. But

what discipline is it that studies the principles of theology? It is a delicate question, to which a

number of answers are possible. First, and least likely to be of interest today, is the denial that any

discipline could exist above the revelations of scriptures such as the Torah, Quran, or New

Testament. That is the exoteric view. Second, and more positively, there is metaphysics, the study

of the principles of existence and nonexistence, including those of God. This is unbounded by the

dogmas of any one religion, since its principles, if true, must be universal. Metaphysics is an

esoteric study, in the sense that it concerns not the outward forms but the inward ( eiso) side of

religion. Basarab Nicolescu refers to one particular development of it, associated with the name of

Rene Gunon, under the name of Tradition. Third, there is theosophy, broadly definable as the

experiential study of things divine.

The theosophical investigation of the powers behind and within the universe, which some call God

or the gods, is rightly held in suspicion: history is too full of cranks and fanatics who have

pretended to such intimacy. Very occasionally, however, a theosopher appears whose claims

demand serious attention by those in search of wisdom. Jacob Boehme is such a one: his claim rests

both on his unimpeachable personal integrity, and on the spiritual fruitfulness of his theosophic

findings. Now, if Basarab Nicolescu is correct, there is a third warrant, in the applicability of

Boehmes system to the problems facing modern science, and indeed modern humanity.

The reader will find in this book an admirably lucid summary of some of Boehmes findings,

supplemented by primary sources from the theosophers own writings. If fruitfulness is at issue,

then this book is one of the richest fruits to grow from the Boehmian tree. Put as simply as possible,

its thesis is that Boehme, through some faculty of supersensory vision, was able to behold the

principle behind the creation and evolution of the cosmos. If that were in any way true, such

knowledge should definitely be of interest to contemporary science. Moreover, Boehme does not

stop at explaining how the cosmos came into existence an unsolved question, but one with which

physics is at least comfortable but continues to explain how and why it has evolved since then. In

order to discuss this, he is obliged to touch on the ultimate qualities of good and evil and on their

deepest roots in the divine nature. The time has come, Basarab Nicolescu suggests, for science to

stop cutting itself off from such matters and concerns, as if they were any less real than the waves

and particles to which physics has reduced our world.

Boehmes first principles are the three metaphysical forces behind the universes existence. They

begin not with God, which is the first Being, but with the Ungrund of Non-being (or Beyond-being)

in the Sight of which even the Creator and its cosmos are as nothing, yet which paradoxically gives

rise to them both. Here Boehme raises to its uttermost limit the hermetic principle of polarity as the

generator of existence, and also plumbs to its depths the problem of what we experience as evil.

Boehmes second series of principles, seven in number, unfurl the development of the cosmos and

of its creative witness, the human mind and soul, revealing the tragedy and the promise that underlie

cosmic and human evolution.

In his deservedly popular work, A Brief History of Time (New York: Bantam Books, 1988), Stephen

Hawking concluded with enigmatic musings on the existence or non-existence of God, in a

Next page