CONTENT

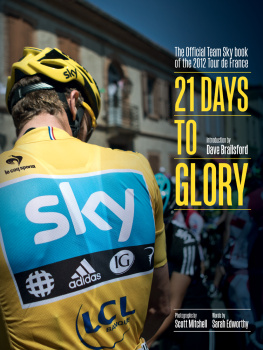

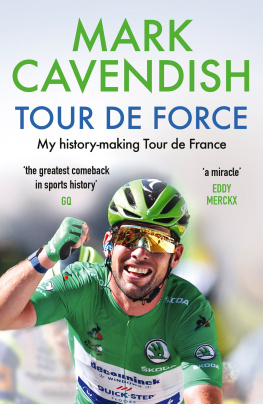

In 2010 we launched Team Sky as a professional road-racing outfit with the aim of a clean British rider winning the Tour de France within five years. The greatest prize in cycling had never been won by a Briton, so it was time to set the record straight. On Sunday 22 July 2012 we achieved this aim, and it was a proud moment. The sight of Mark Cavendish winning on the Champs-Elyses led out by Bradley Wiggins in the yellow jersey in front of phenomenal British support waving Union flags well, you couldnt script a more perfect way of realising an ambition.

We had set ourselves five years, but the win came together in just three. Our first season, 2010, was a baptism of fire. We had 64 new people, 14 nationalities, a brand-new team operating with a new philosophy, run by people who had never managed a professional road-cycling team before. Id been Performance Director at British Cycling for 11 years by then and it seemed normal to take the business-as-usual stuff from there and start somewhere else, but I didnt recognise how refined the Tour demands are. It was a difficult year. We were all out of our comfort zones. Theres a point where if you want to fundamentally change behaviour, there has to be a threshold where the suffering is bad enough, or the reward great enough, for people to change. We reached it.

Going into 2011, the second season, we had a more structured approach with a clearer idea about the simple things we wanted to focus on. From a performance perspective, we made progress. For Bradley in particular, it was as if the penny dropped. He was experienced, he was mature, he believed in his coaching team and he started to get it in terms of the amount of work he was putting in. We started to see signs of Tour-winning potential. Going into the Tour we had high ambitions, but ultimately he crashed, broke his collar bone and that was that. He bounced back and collectively we went into our second off season as a highly motivated, highly driven team. Bradley had won the Dauphin, the big race before the Tour de France, and that was a big, big step forward. In the Tour of Spain we finished second and third our first podium in a Grand Tour. We were moving in the right direction. We had a clear model of how to mount a challenge to win the Tour.

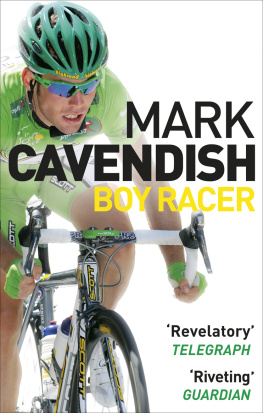

A lot of the riders had been on two-year contracts, so for 2012 we had an opportunity to bring in riders for a specific purpose, which had a huge impact. To pursue our goal of winning the General Classification, we had identified the need for highly talented climbers. We signed Richie Porte, Kanstantsin Siutsou and Christian Knees. With world champion Mark Cavendish and his helper Bernie Eisel, that made five new riders in the Tour team of nine, selected from our squad of 28. We then got these super-talented cyclists to train and race together as much as possible so that when they went into the Tour it was business as usual, rather than a brand new challenge.

As a team we had moved from the conceptual phase into a more tightly refined operation bound by our philosophy. Everyone was aligned, pulling in the same direction. Bradley was in great shape, in great form. For the entire team, the Tour would be 21 days of protecting Bradleys focus on the road, against illness or injury, against feeling unsettled to allow him to deliver victory in Paris. But for those 21 days you dont think about the outcome, you dont think about the what ifs; you focus instead on the process, and on delivering that on a minute-by-minute, hour-by-hour, day-to-day basis, because focusing on the process increases the chance of getting the outcome you want

The greatest prize in cycling had never been won by a Briton. It was time to set the record straight.

Dave Brailsford

On paper, the tactics for the 2012 Tour campaign looked simple. Survive the first week, take time off our rivals in the second, then defend all the way to Paris. But first you have to roll down the start-house ramp. You have to commit yourself to the ticking of the clock. Im always nervous before a big race, so I wasnt feeling great, said Edvald Boasson Hagen. But I knew that I had trained well, I was well prepared. Everyone has a special feeling before the Tour starts. Its the race you train all year for. There was a lot of expectation from ourselves and from outside the team. It was time to see what would happen.

For all the talk of teamwork and working selflessly on behalf of the team leader, three of the 21 stages on this 2012 Tour are time trials when each rider is on his own. As a group, they have absorbed a precise presentation of the 6.4km individual time-trial stage on the screen at the front of the bus. They have studied the detailed information in the race book. They know from personal recces that its quite technical, with changes in direction, in road width, type of surface, grates on the racing line, and so on and they know it is up to themselves individually to get pumped up, in the zone, prepared to turn themselves inside out to ride to the absolute edge of their capability. As Dave Brailsford says, A time trial is called the Race of Truth because youre on your own. No one else is involved. It is a question of how much you can push and hurt yourself over a given time in a given event. These guys have their own way of preparing for the focus that requires. Bradley is remarkable; in the last hour and a half, he listens to music, he psyches himself up, he knows the process to go through until his heart is pounding, his nerves are going, his body releases adrenalin. These guys figure out that feeling bad is probably good.

A time-trial day calls on several levels of mental toughness. With 198 riders going at two-minute intervals, there was a lot of hanging around before the days seven-odd minutes of all-out sprint effort. To reach the optimum level for physical performance, each rider has a pre-race massage to loosen the body before warming up on turbos to a rate set by Tim Kerrison, head of performance support, and measured by heart-rate monitors. The carers give out cotton wool daubed in a decongestant to clear the airways and ensure efficient breathing to feed oxygen to the muscles. (Chris Froome, in his excitement, left the cotton wool in his nostrils when he went down the ramp and still came 11th. If he did that time just breathing through his mouth, how fast can he go breathing through his nose and his mouth? laughed Brailsford.)

Wiggins has made time trials his domain, but coming into the Tour he was facing unprecedented media attention. How did he feel to be favourite? Had he peaked too soon? Behind his mirrored, specialist time-trial glasses, Wiggins was perfectly composed. In the past we had gone to races early in the season and used them for training, but this year we had gone to races to try and win, to learn how to start leading races and defending a lead, and to familiarise ourselves with all the hassle, the press, the extra stuff that goes with being dominant, says Brailsford. Wed thought, lets get used to that until it feels normal.

When Wiggins burst down the ramp in Lige, his aim was to come out on top of the timings though he had conceded in a team meeting the previous evening that the only man who might edge him out was Fabian Cancellara, the Swiss time-trial specialist known as a motorbike in prologues. Wiggins rolled down in classic form: not pushing too hard at the start, maintaining a consistent pace throughout, ending the day a mere seven seconds off Cancellara with his rival for General Classification honours safely behind him.