Table of Contents

DEDICATED TO THE PEOPLE OF THE BORDER.

Thanks to Cinco Puntos Press, Lee, Bobby and Johnny Byrd. Thanks to those

who read the initial manuscript and whose comments greatly improved the

quality of the book: Molly Molloy, Debbie Nathan, Sito Negron,

Vanessa Johnson, Dr. Richard Pineda and Mike Stevens.

Thanks to Dr. Tony Payan and Karla Guevara

who helped track down valuable information.

INTRODUCTION

2008 WAS DIFFERENT

El Paso sits on the Rio Grande, aka the U.S./Mexico border, across from Ciudad Jurez. I was born here. My co-author Susie Byrd moved to El Paso with her family when she was seven. Each of us grew up a few minutes from the river and Ciudad Jurezthis experience is the lens through which we write this book.

This is where Latin America and North America meet to form the largest binational community in the world. Its the point at which the 400-year-old Camino Real del Tierra Adentroafter having passed through Mexico City, Durango, Chihuahua and Jurezcrosses into present-day U.S. territory, continuing north through El Paso and on to Santa Fe, New Mexico.

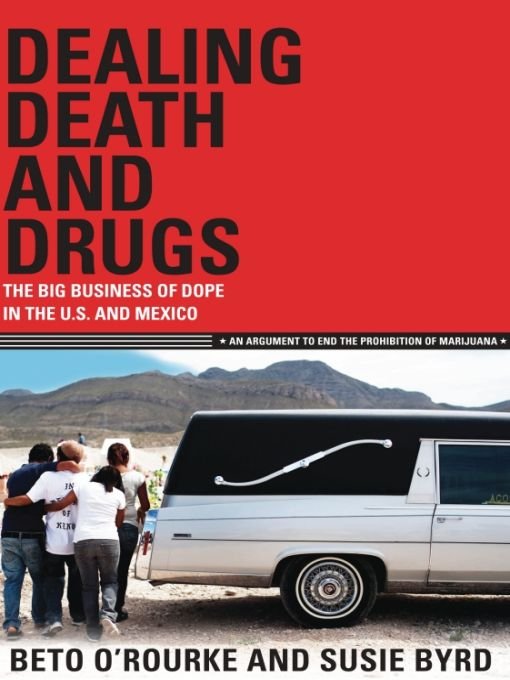

This book is about what happens in our community when the value of the drugs that move through this ancient trade corridor exceeds the value of human life. We will explore the economy of the illegal drug trade, with a focus on that drug the cartels find most important to their bottom line: marijuana. With first person accounts, court transcripts and federal data, we will demonstrate how this simple weed has become the center of a multi-billion dollar industry. This industry is powerful enough to threaten governments, command horrifying violence and inspire the creation of outsized laws and budgets in the U.S., laws which end up strengthening the very cartels they were created to put out of business. We conclude by reviewing a previous experiment with prohibition and offer a solution that can undermine the power of the cartels and produce positive outcomes for both the U.S. and Mexico.

At first drive through, El Paso can feel like a richer, if more staid, suburb of Jurez, and Jurez can feel like a more exciting, if poorer suburb, of El Paso. El Paso has the tall downtown bank buildings, the ordered system of freeways and streets, the manicured lawns in distinct subdivisions. Jurez has the street life, the staggering swings between rich and poor and the invigorating chaos of 350 years of ad-hoc construction and twisting streets named for ghosts of the revolution. Bob Dylan sings about Jurez; El Paso gets Marty Robbins.

But the cities have each other. El Paso is over 500 miles from the Texas state capital and light-years from Washington D.C.; Jurez is the same distance, for all practical purposes, from Mexicos centers of power and population. So far away from the interest and focus of the state or feds, isolated from other major cities by hundreds of miles of barren desert plateau, the conjoined communities have long relied on each other in the development of their commerce, families and culture.

The vast majority of El Paso is of Mexican descent. If charted, the family trees of most would show ancestors from Jurez and other, smaller cities of the frontier state of Chihuahua. Cross-border family reunions are a common, daily affair, taking place in both Jurez, and especially these days, El Paso.

There is a distinct Spanish spoken in El Paso, pocho, inflected with code-switched local phrases that I heard and spoke as I grew up. I only learned later in El Paso High Spanish class that ay te watcho is not the proper way to take leave of ones friend.

While not a perfect melting pot, El Paso has long been a remarkably tolerant community. Many of my friends in grade school were first-or second-generation U.S. citizens whose families crossed over from Mexico. Others were Mexican citizens and claimed residency at the home of El Paso relatives or family friends in order to attend school here. The distinction between Anglo- and Mexican-American stood out (as do all distinctions at that age), but it was a distinction that lacked enough difference or meaning to determine who would or would not become a friend.

All of us spent time in Jurez. When we were young, wed go to the markets and restaurants with our parents. As we got older, it was the nightclubs and bars. And when we were adults, it was back to the restaurants and markets with our own kids. Jurez was a destination for pleasure and fun, a place to take visitors to gawk and be entertained and then go home. You drank beer for 50 cents a bottle, bought some trinkets at the market and maybe walked by the old cathedral. Having to pay your way out of a real or imagined traffic violation was about the worst that could happen.

Growing up, I would hear about drug busts on the news, but it was such a common occurrence that it tended to blend into the background. Like the weatherman forecasting sunshine. While there is a rich history of black market trafficking in Jurez, going back at least to the U.S. alcohol prohibition of the 1920s, as a child I didnt understand or make the connection between the city next door and the news about drugs. If I ever did, it was only with the most passing of interests.

The news reports of cocaine or marijuana seizures were at times followed by one of a number of anti-drug commercials whose tag lines I can still remember (e.g. This is your brain on drugs, or I learned it from watching you, dad!). In hindsight, their ineffectiveness is obvious.

But at the time it was not something I paid much attention to, since I didnt use drugs and I wasnt interested in the subject. This was not the case for all of my friends though.

Some friends tried drugs, or at least had enough working knowledge of drugs to convince the rest of us that they knew what they were talking about. I remember a seventh-grade classmate at Mesita Elementary who not only bragged about getting high, but was caught selling dope to a janitor. He was the exception. Most kids I knew didnt try pot until later, when it was offered to them at high school parties or while drinking in the functionally all-ages bars of Ciudad Jurez.

As I grew older and listened to the news a little more carefully, I learned that Jurez was the crossing point for many of the drugsand certainly all of the dopesold and used in El Paso. Every so often there would be news of another big bust; tons of marijuana interdicted at the border coming over from Jurez or bundles of cash and cocaine uncovered in a stash house in El Paso. The sheer tonnage and enormous street value of these interdictions made it obvious that the Jurez/El Paso land port was an important logistical hub in the North American drug trade. But I didnt think that it affected me, so I didnt pay much attention.

In college, marijuana was even more available than it had been in high school. People smoked openly at parties, in dorm rooms and out on the streets.

Given everything that has happened in Jurez in the last few years, the fact that it is now the deadliest city in the world and the focus of the combined drug interdiction efforts of the U.S. and Mexico, it amazes me how little I knew or cared about these issues before. Having lived 35 years of my life within the front lines of the declared drug war; having seen drug use around me since middle school; having known that billions of dollars in drugs were transiting through my community until 2008 I cant remember ever thinking about drug policy, much less caring about it.