THE HENRY L. STIMSON LECTURES SERIES

The Henry L. Stimson Lectures at the Whitney and Betty MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies at Yale.

Published with assistance from the Louis Stern Memorial Fund.

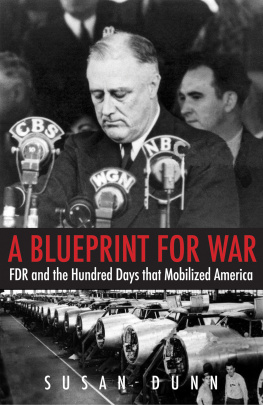

Copyright 2018 by Susan Dunn.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in type by

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017954129

ISBN 978-0-300-20353-0 (hardcover: alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Joseph J. Ellis

Contents

CHAPTER ONE

The God of No Foreign War

M R. PRESIDENT, A REPORTER asked Franklin Roosevelt at a press conference on March 4, 1941, would you care to give us a reminiscent thought on eight years ago today? It was the first day of his ninth year in the White Housea milestone no other U.S. president had reached. We have a different kind of crisis, Roosevelt replied, a world crisis instead of a domestic crisis. It is probably more serious than the one eight years ago. I think we might let it go at that.

Everyone knew what the president meant. Another journalist noted that FDR, suffering from a bad cold, spoke in such a low voice that those in the back could hardly hear him. The fifty-nine-year-old president joked with reporters and, as usual, puffed on a cigarette in an amber holder set in his mouth at a jaunty angle. But, the reporter wrote, he did not radiate any of the cheerfulness and hope that marked his accession to the White House in 1933, when people could optimistically sing Happy Days Are Here Again.

At that first inauguration in 1933, on a grim, overcast March day in the depths of the Great Depression, FDR had taken the oath of office and then addressed the vast crowd outside the Capitol: I assume unhesitatingly, he said, the leadership of this great army of our people dedicated to a disciplined attack upon our common problems. The new presidents self-confidenceand his unforgettable declaration that the only thing we have to fear is fear itselfsignaled the brave, buoyant beginning of the period historians have named the first Hundred Days.

Those months saw significant changes in economic policy. FDRs administration restored solvency to the battered banking system, provided jobs to millions of the unemployed, extended relief to farmers plagued by drought and foreclosures, constructed power plants in the Tennessee Valley, and imposed sweeping regulations on a financial system on the brink of ruin.

Two years later, in the summer of 1935, Roosevelt swung further to the left and took more bold steps to ease the domestic crisis. Congress passed some of the New Deals most significant and enduring social programs: Social Security; the National Labor Relations Act; the Works Progress Administration, which gave millions of jobs to blue-collar workers as well as to artists, writers, actors, and teachers; the Rural Electrification Act; and the Revenue Act, which lowered taxes on small businesses and increased them on large inheritances. Historians have called this innovative period Roosevelts second Hundred Days.

On November 5, 1940, when the president was elected to that unprecedented third term, he faced still another crisisa worldwide military, political, and moral catastrophe. On the other side of the planet, Japan had extended its tentacles deeper into China and was rapidly rearming its navy to challenge American power in the Pacific Ocean. In the Atlantic world, almost all of the European democracies had fallen under the extraordinary onslaught of the unstoppable Nazi army and air force. Adolf Hitlers relentless aggression had transformed the continent into one huge prison house. As Hitler described the stakes of the war he had provoked, Two worlds are in conflict, two philosophies of life. Only one could survive.

Unlike in Roosevelts first Hundred Days in 1933 or his second in 1935, far more than the nations economic and social well-being was now at stake. The lives of tens of millions of people around the world and the fate of free and democratic governments everywhere hung in the balance. Judeo-Christian morality along with the Enlightenment principles of freedom under law, individual rights, and due process trembled on the verge of extinction.

Those cold and wet winter months between November 1940, when Roosevelt and his team began delineating a strategic plan for possible war, and March 1941, when he signed the Lend-Lease Act, constituted his third Hundred Days. It was ultimately the most vital and consequential period of his presidency: during those hundred days, the president would initiate the pivotal programs and approve the strategic plans for Americas successful leadership in World War IIleadership on which hinged the survival of the civilized world.

This period marked a critical change for FDR. A master of communication and persuasion, he had fluctuated, temporized, calculated, and shifted for years in response to a public that was more receptive to isolationist leaders who rejected the foreign entanglements that had pulled the country into the First World War. It had been simpler in 1914 when, as Woodrow Wilsons young, bellicose assistant secretary of the Navy, he had freely criticized the president for not taking stronger action at the outbreak of the war. He complained then to his wife, Eleanor, that gullible Americans were being fed a lot of soft mush about everlasting peace.

Hitler and his Nazis, who swept into power in Germany in 1933, changed the dynamic of global politics; they were a malignant menace that grew year by year. But for most of the 1930s, FDR took no stronger action than words. In January 1936, as Hitler was threatening to march into the Rhineland in flagrant violation of the Treaty of Versailles, FDR proposed in his State of the Union message that the United States adopt a well-ordered neutrality and use its moral influence to combat intolerance and autocracy in the world.

The following August, speaking in Chautauqua, New York, he emotionally expressed his horror of war. I have seen war, he said, recalling his visit as assistant secretary of the Navy to the frontlines in war-ravaged France in 1918. I have seen war on land and sea. I have seen blood running from the wounded. I have seen men coughing out their gassed lungs. I have seen the dead in the mud. I have seen cities destroyed....I have seen the agony of mothers and wives. I hate war. His fervent hope was that envy, hatred and malice among Nations had reached their peak and would be succeeded by a new tide of peace and good-will. The noblest

In public, especially before the 1936 presidential election, the president allied himself with the anti-interventionism that grew ever more intense as the European scene darkened. But privately, he knew that promises of no political commitments which might entangle us in foreign wars could not stop Hitler and his Italian ally, Mussolini, from starting a war that would indeed entangle the United States.

Even so, internationally minded newspapers reacted positively. The quarantine talk was statesmanlike in theme and compelling in argument, editorialized the

Next page