Copyright 2018 by Sunil Amrith

Cover design by Rebecca Lown

Cover image View Stock/Getty Images

Cover 2018 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Basic Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.basicbooks.com

First Edition: December 2018

Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Basic Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Names: Amrith, Sunil S., 1979 author.

Title: Unruly waters : how rains, rivers, coasts and seas have shaped Asias history / Sunil Amrith.

Description: First edition. | New York : Basic Books, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018020666 (print) | LCCN 2018036442 (ebook) | ISBN 9780465097739 (ebook) | ISBN 9780465097722 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: WaterSocial aspectsAsiaHistory. | Bodies of waterSocial aspectsAsiaHistory. | Water and civilization. | AsiaCivilizationEnvironmental aspects.

Classification: LCC DS12 (ebook) | LCC DS12 .A54 2018 (print) | DDC 950dc23\

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018020666

ISBNs: 978-0-465-09772-2 (hardcover), 978-0-465-09773-9 (ebook)

E3-20181029-JV-NF

Crossing the Bay of Bengal: The Furies of Nature and the Fortunes of Migrants

Migration and Diaspora in Modern Asia

Decolonizing International Health: India and Southeast Asia, 193065

For Theodore and Lydia

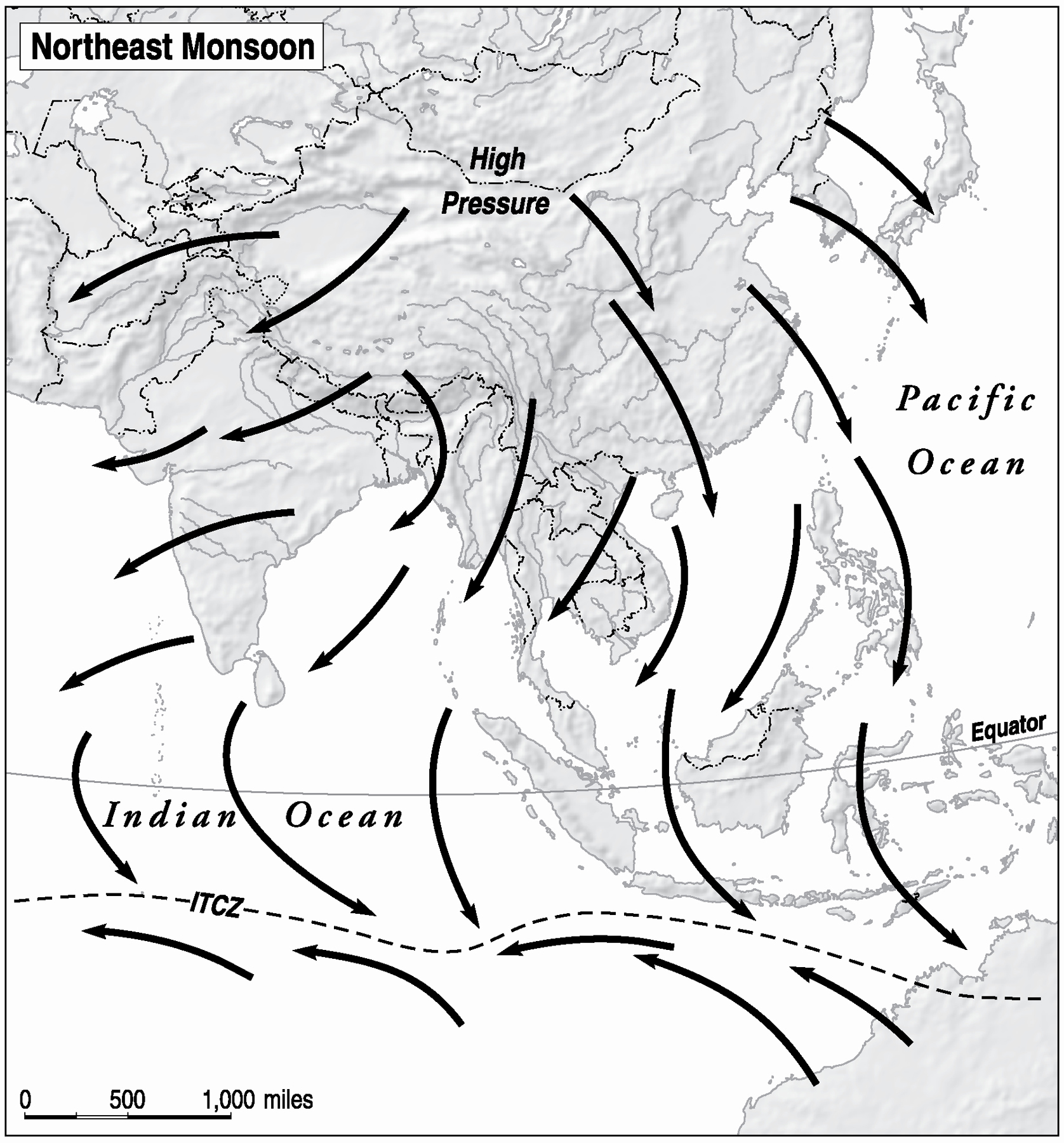

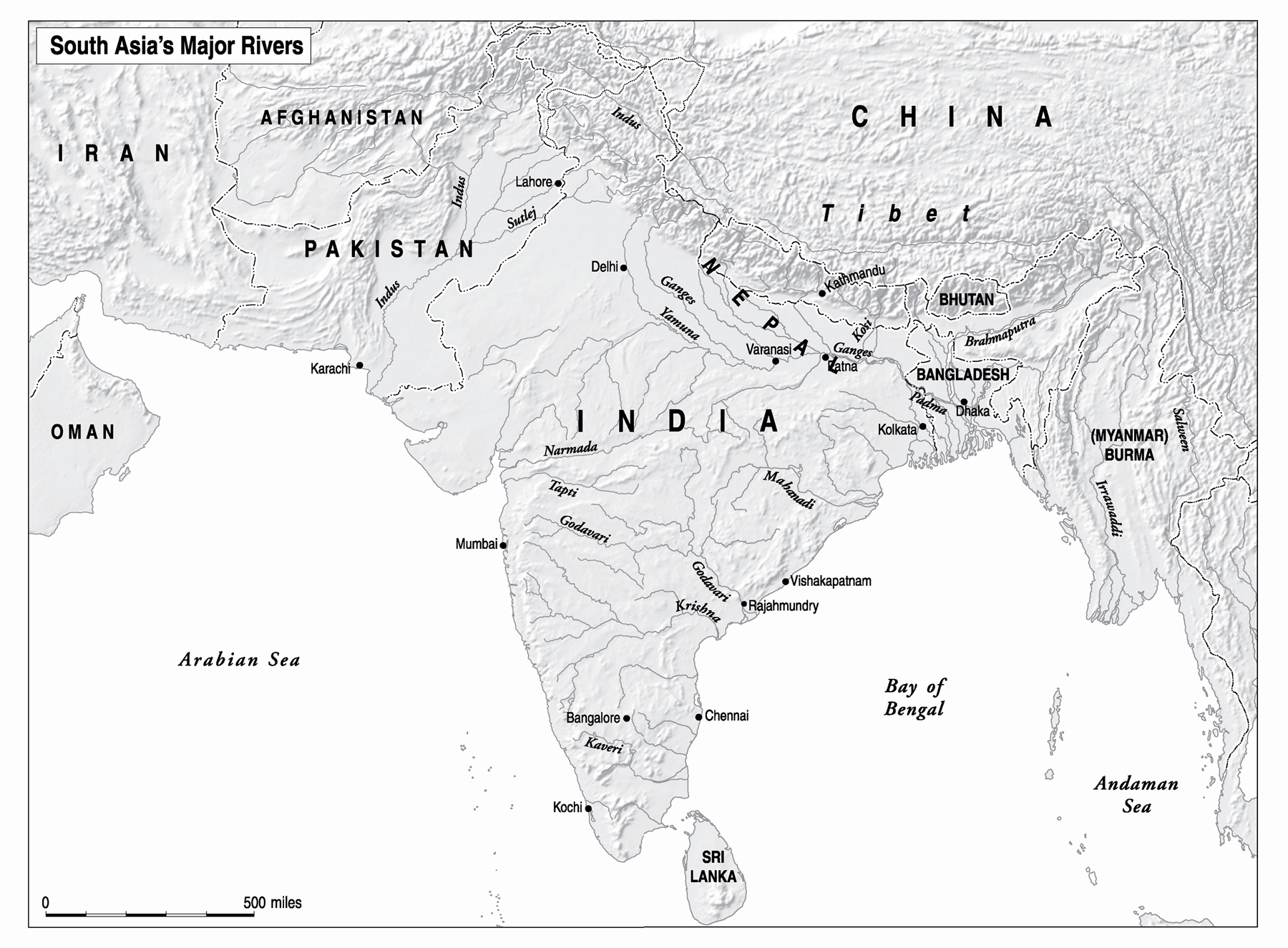

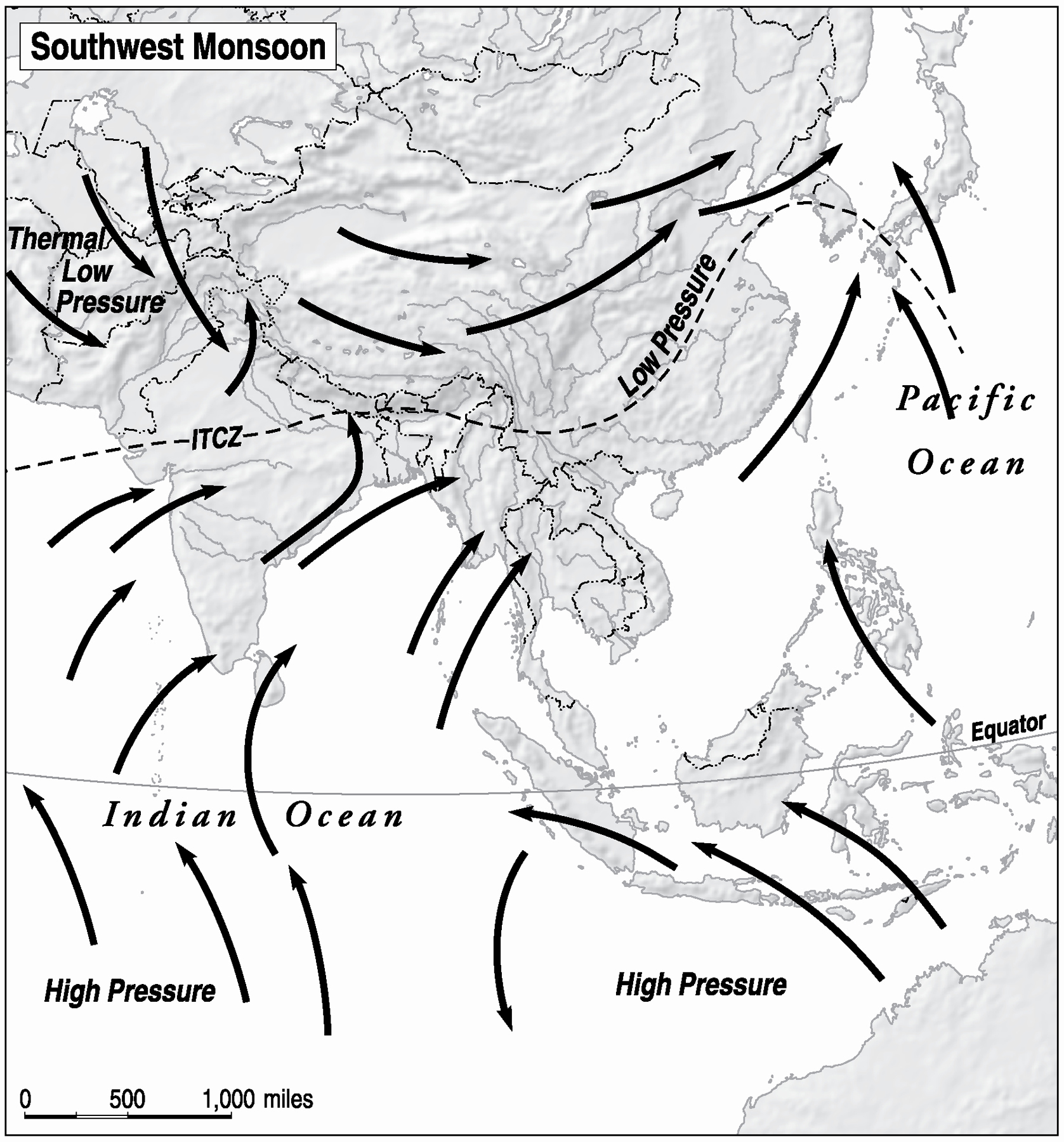

Map showing the winds during the northeast monsoon, which blows from December to March.

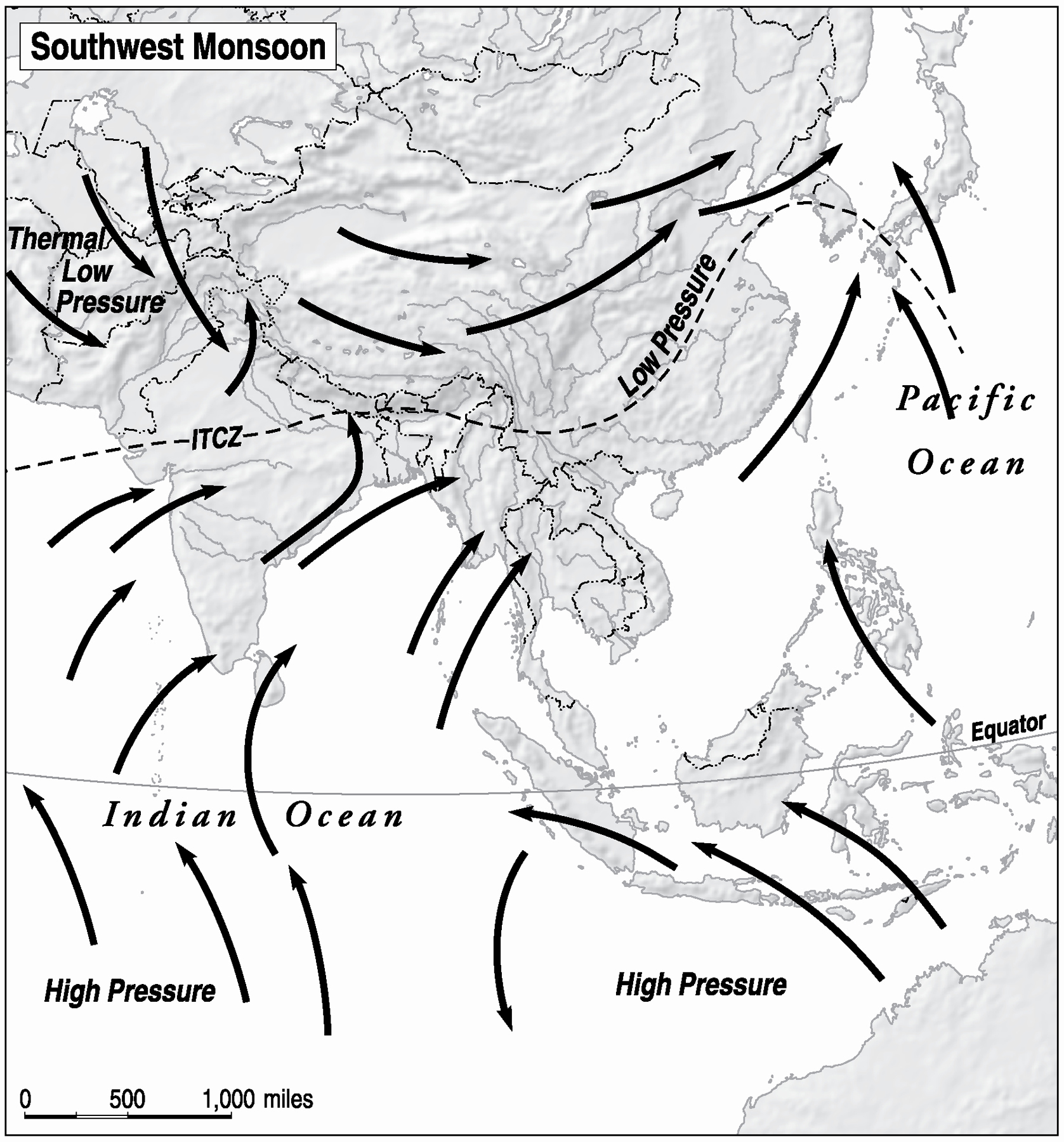

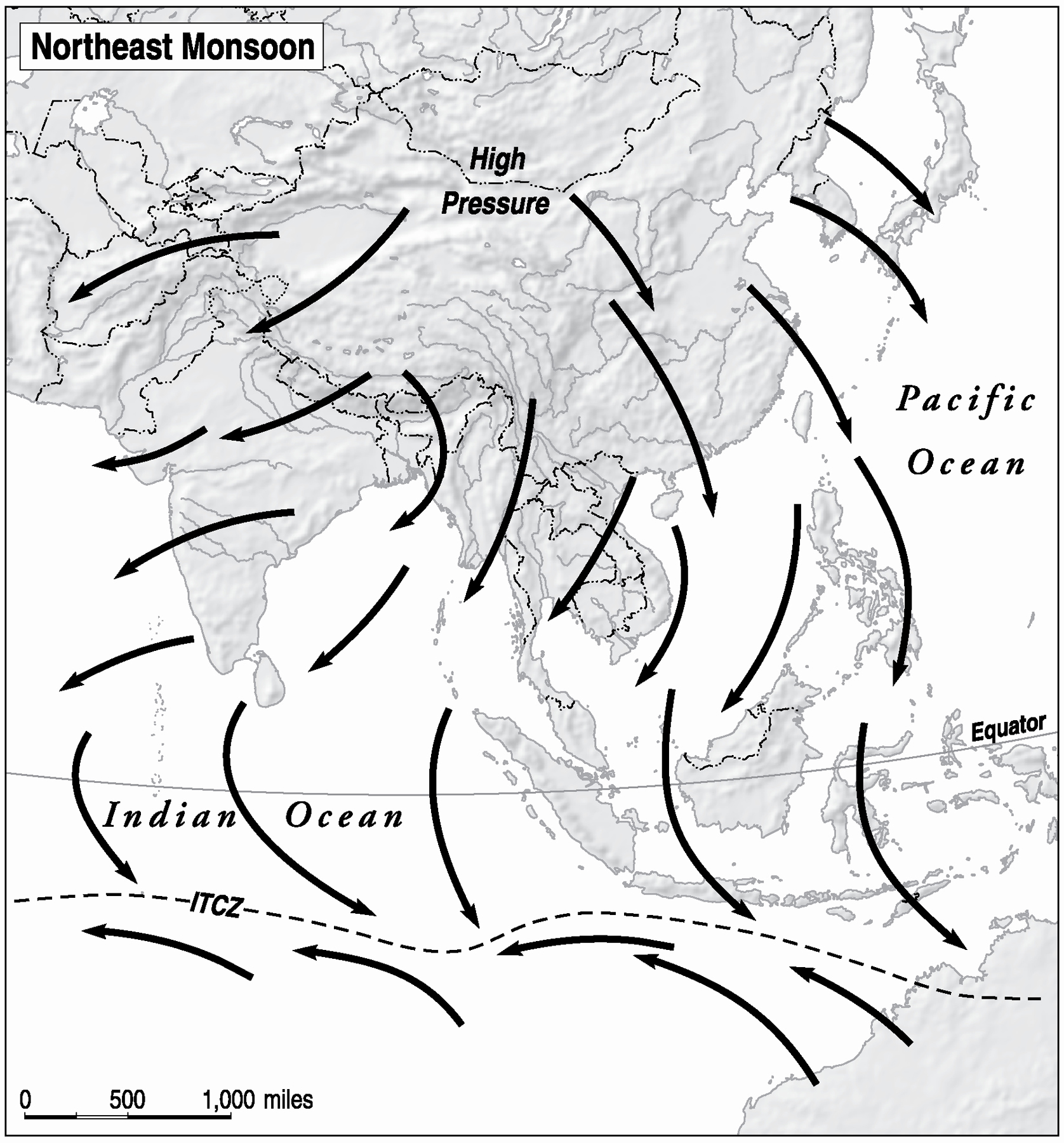

Map showing the winds during the southwest monsoon, from June to September.

M ANY OF THE PLACES I WRITE ABOUT IN THIS BOOK HAVE BEEN known by different names at different points in time. As a rule, I have used the names that correspond to the period I am writing aboutto cite a few examples, I use Bombay, Madras, Calcutta, Poona, and Rangoon when I am discussing the colonial period and the early decades after independence; I switch to Mumbai, Chennai, Kolkata, Pune, and Yangon, respectively, when I am talking about more recent history, as those names were formally changed in the 1990s. I adopt a similar strategy when it comes to country names: for example, I use Ceylon and Malaya when discussing the colonial period, and Sri Lanka and Malaysia when writing about the post-independence era.

For clarity I have transliterated words from South Asian languages in a way that reflects common practice in the region rather than employing the formal diacritical marks favored by scholars of South Asian languages.

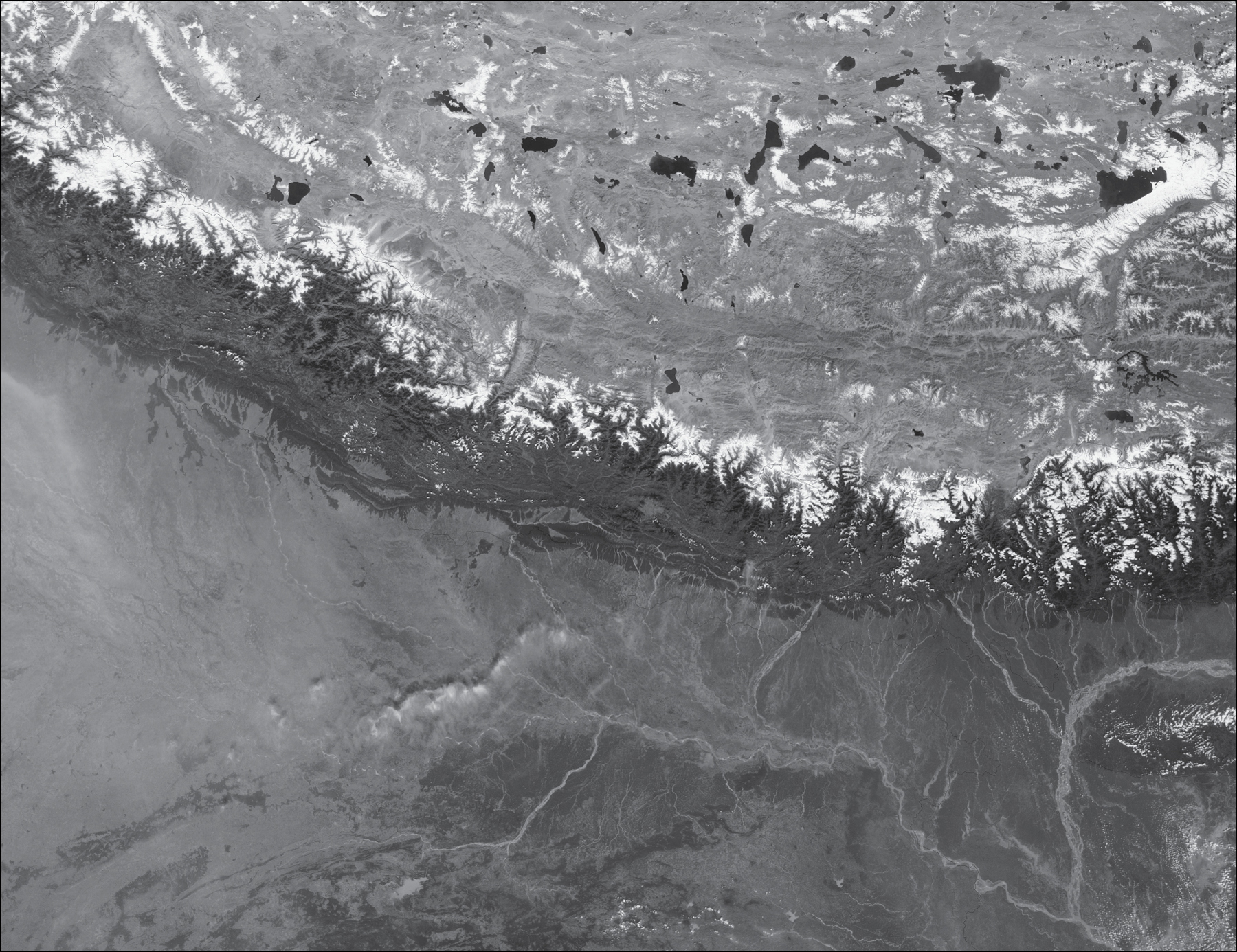

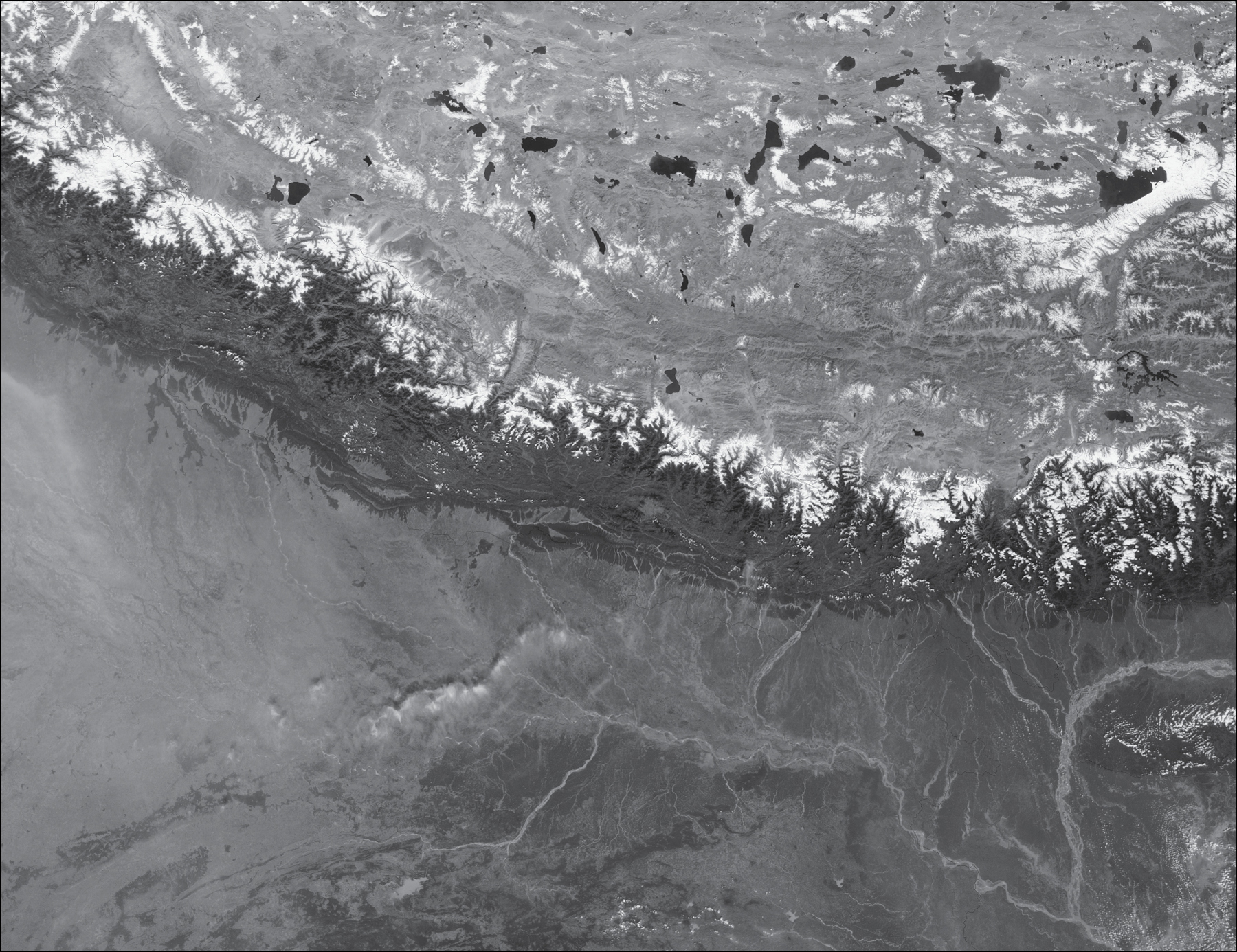

A NASA satellite image from October 27, 2002, showing a Himalayan mountain range and the rivers that descend from the Tibetan Plateau into North India. C REDIT: Jacques Descloitres, MODIS Rapid Response Team, NASA/GSFC

L OOKING DOWN FROM ORBIT, THE LENS OF A NASA SATELLITE LANDS upon this patch of Earth. In the upper half of the picture lies the curve of a Himalayan mountain range, fringed by the iridescent lakes of the Tibetan plateau.

The satellite picture is a snapshot of a single moment on October 27, 2002. But there are layers of history embedded within it. It shows us the outcome of a process that unfolded in deep time. Approximately 50 million years ago, the Himalayas were created by the collision of what would become the Indian peninsula, which had detached from Madagascar, with the Eurasian landmass. The island buckled under the edge of Eurasia, pushed up the Tibetan Plateau, and eradicated a body of water later named the Tethys Sea. Geology, looking further than religion, E. M. Forster wrote in A Passage to India, knows of a time when neither the river [Ganges] nor the Himalayas that nourish it existed, and an ocean flowed over the holy places of Hindustan.

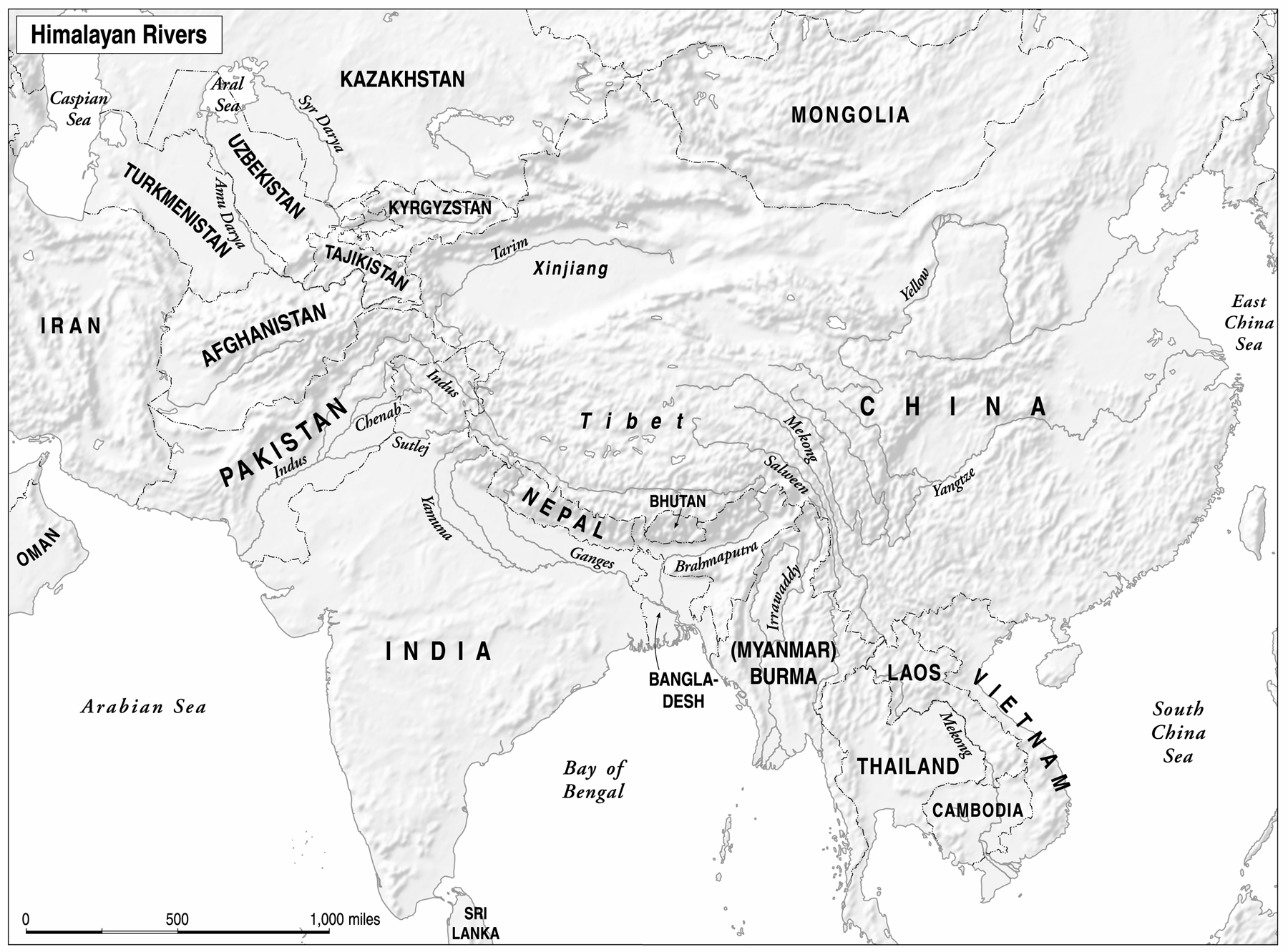

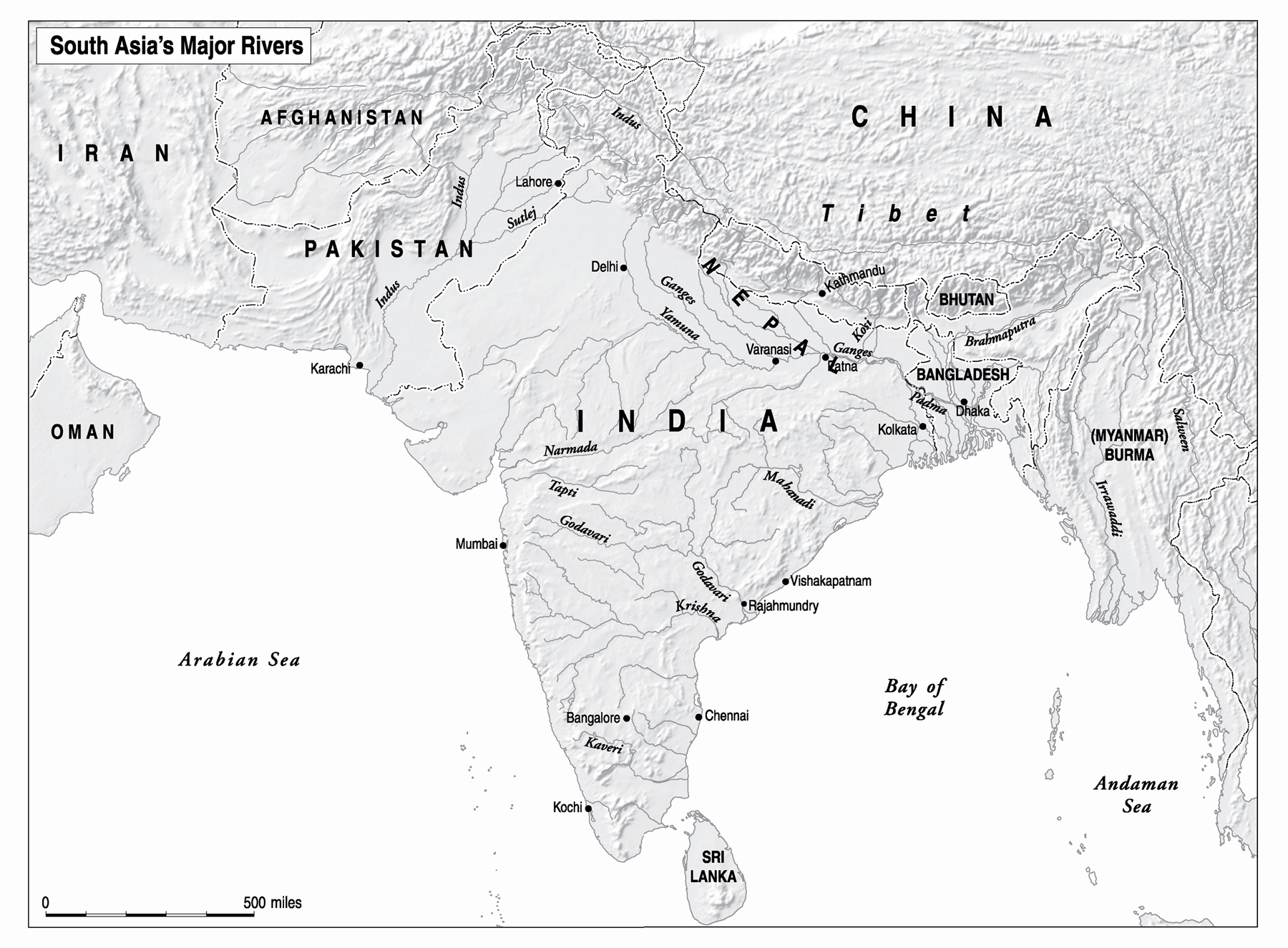

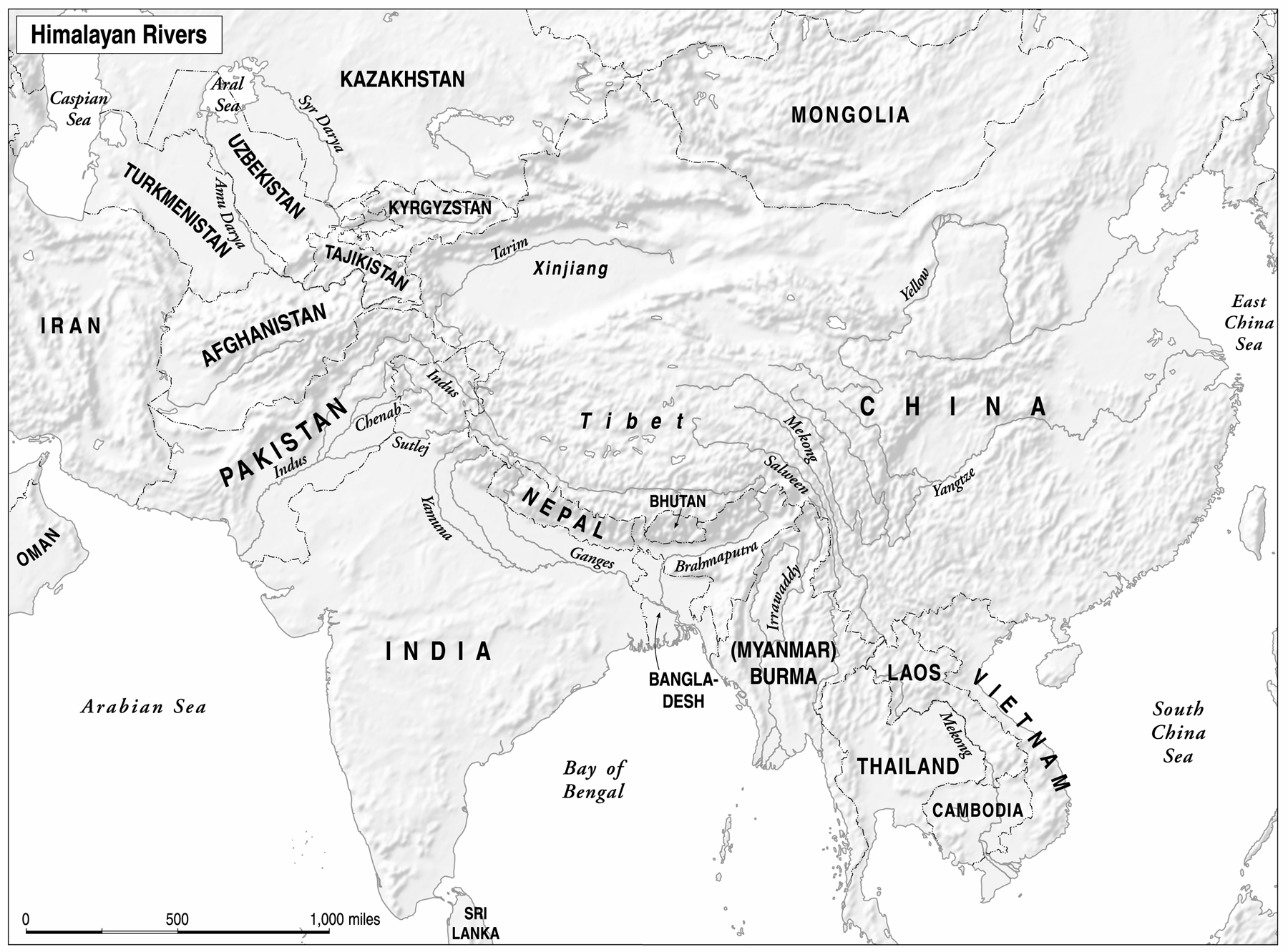

So massive are the mountains, so heavy is their concentration of snow, ice, heat, and melting water that they shape Earths climate. Asias great rivers are a product of this geological history. They flow south and southeast, and they have shaped the landscape that is visible here: the force of the rivers descending from the mountains eroded rock, creating the gorges and valleys. Over centuries the rivers have carried silt and sediment from the mountains; they have deposited them along Asias valleys and floodplains to sustain large human populations. Writing in the 1950s, guided by maps and not yet by satellite photographs, geographer Norton Ginsburg described Asias mountain core as the hub of a colossal wheel, the spokes of which are formed by some of the greatest rivers in the world.

And then your eye comes to rest on what was invisible to the satellite but is now superimposedevidence of a more recent history lies in the borders that dissect the rivers, their shapes governed by bureaucratic, not environmental, logic. Within the frame of this image alone, the mountains run through southwestern China, Nepal, Bhutan, and northeastern India. The rivers are more unruly; they spill beyond the frame of the photograph. From mountain peaks flow ten great rivers that serve a fifth of humanitythe Tarim, the Amu Darya, the Indus, the Irrawaddy, the Salween, the Mekong, the Yangzi, the Yellow River, and, at the heart of this photograph, the Ganges and the Brahmaputra. The Himalayan rivers run through sixteen countries, nourished by countless tributaries. They traverse the regions we carve up as South, Southeast, East, and Central Asia; they empty out into the Bay of Bengal, the Arabian Sea, the South and East China Seas, and the Aral Sea.

Look at the left of the picture and you can see a more compressed history. The haze of pollution that hangs over North India is a composite brown cloud of human-produced sulfates, nitrates, black carbon, and organic carbon. Aerosol concentrations over the Indian