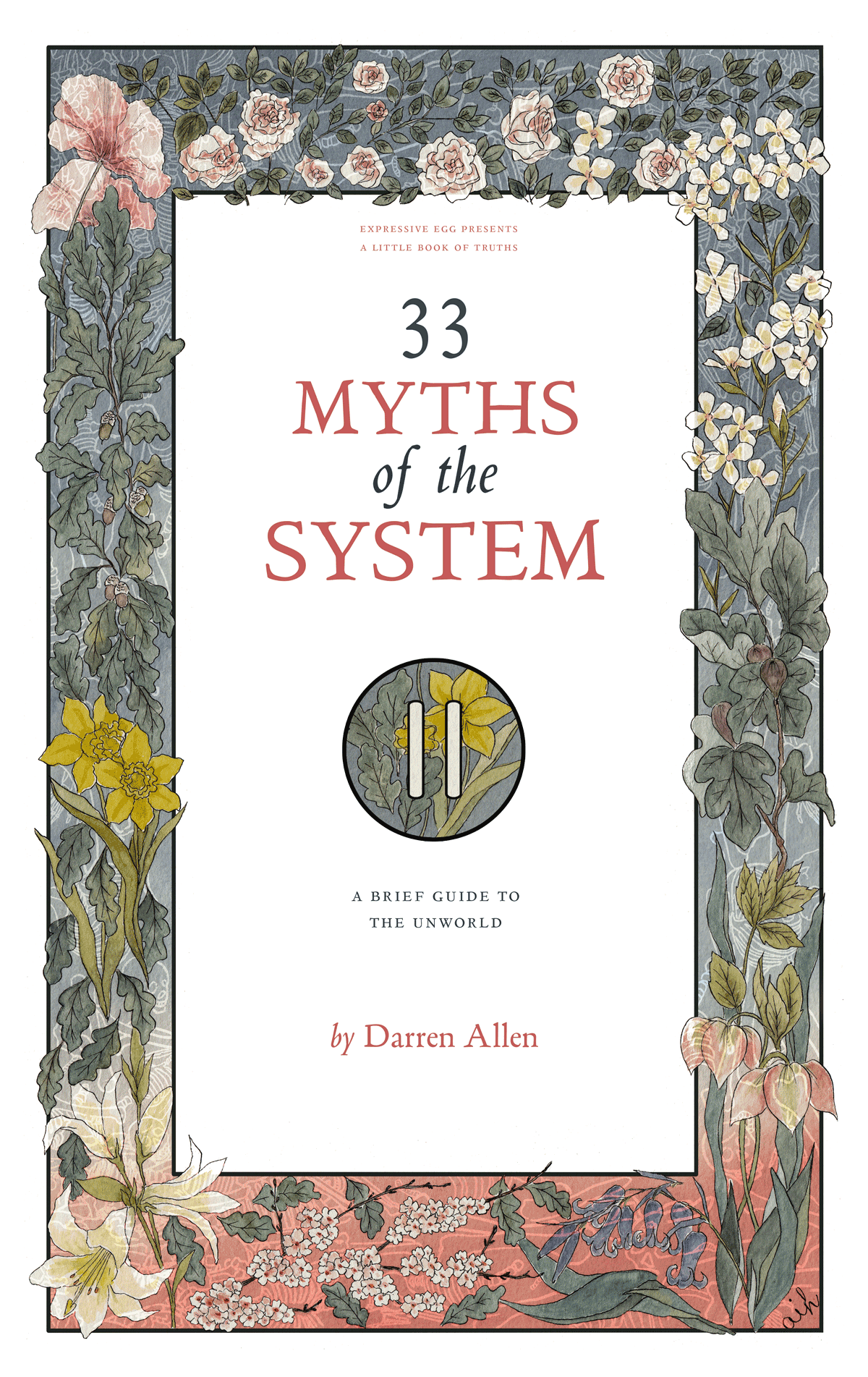

33 Myths of the System

Darren Allen

I would like to thank David Edwards, of Media Lens, for his extraordinarily generous support over the past ten years.

Cover design and text layout by Darren Allen.

Cover illustration by Ai Higaki.

The digital version of this book is free and is offered under a creative commons licence; specifically an with me first. Ill probably say yes.

Contents

i. Preface to the Series:

The Revolutionarys Paradox

scentate [ sntet ]

vb not being able to work out whether the problem comes from oneself, or whether it comes from the situation

- is your sadness the terrible truth and your happiness a mask, or is your happiness the profound reality of your life and your sadness just a selfish episode? Is your difficult relationship with your lover causing you to be unhappy, or is your unhappiness making the relationship difficult? Is it your train that is leaving the station, or another train you can see moving through the window? Is it you, or is it the world?

On the one hand it is impossible to change your personal life how you (and others) feel, perceive, think and act unless the institutions which shape and subordinate your life also change. No matter how spiritually enlightened, cheerful, generous or creative you may be, if you have to live in the towns and cities of the world, go to its schools, travel its roads, eat its food, work in its factories and offices, use its hospitals and courts, not only can you do very little with personal or psychological freedom, it is eroded, cheapened and co-opted by its presence in the system. On the other hand it is useless to change the world while people remain essentially fearful, confused, violent and selfish. Not that people are essentially bad; but anxiety, insensitivity, cruelty and egoism are nearly always successful at resisting the healthy, the natural, the convivial and the fair. You dont need a sociologist, a psychologist, a historian or an anthropologist to tell you that men and women are exceptionally good at making a prison out of their freedom.

This is the revolutionarys paradox ; a classic case of scentation . Is the problem out there, or is it in here? Do I change the world, or change myself? People tend to resolve this problem (if they are aware of it at all) by coming down on one side or the other. A prototypical world-changer a committed socialist perhaps might say that mysticism, psychotherapy, psychedelic drug use, even art are kind of frivolous, self-indulgent; at best of private, personal value or even, in the service of socialism, of collective use; but, in the end, well never really be happy until society has changed, until it allows us to express ourselves freely, cooperate creatively and reach our full potential. Until then well always be frustrated. A prototypical self-changer a hippy, lets say, in the original sense, or a mystic might say that faffing about with democracy, riots, unions, activism or revolt changes, essentially, next to nothing. The same groupthink prevails in radical organisations, the same bitchiness, the same dull scripts, the same debilitating compromise and the end results are always, essentially, the same. Changing the world without first changing your mind is the quintessence of futility and doomed to failure.

Taken as a whole these two books, 33 Myths of the System and 33 Myths of the Ego , make the case that both positions are wrong, and both are correct. Until the dissident uncovers the radical reality of his personal life he will never change the world. Until the mystic uncovers the radical reality of social life she will never change her self. To perceive personality and society as they are is no easy matter though. They are stupendously difficult to experience directly; to understand how humans created and continue create the world is like trying to understand a camera by peering at a photograph.

In a book like this, we can, of course, only look at photographs. My intention is to arrange them in such a way that the mechanism which produces them is seen more clearly, and in the seeing, a better camera comes into play.

ii. Foreword to 33 Myths of the System

The system has been ten thousand years in the making. During that time it has taken many localised forms autocratic, democratic, socialist, capitalist but despite superficial variations in structure and priorities, it has remained the same entity. It is now so sophisticated, so pervasive and so invasive, that it is almost impossible to perceive. We may know that something is very wrong with the world we have made, but it reaches so deeply into our experience that when it comes under radical criticism, we defend and excuse it as an extension of our own selves. The myths of the world are our own, and to expose them is to expose ourselves. Even, as we shall see, to read the words the system can be enough to provoke discomfort, the sense of being under attack, or the feeling that the person using the term is an angry or immature misfit.

Chances are though you are aware that something is dreadfully wrong, that the world increasingly resembles hell on earth, that it is rapidly cracking up and that we need a revolutionary alternative. This book is an endeavour to strengthen this insight and to deepen it; to show that the problem is far worse (and, by implication, the solution) is far more radical than is currently and commonly supposed.

Although brief, I have attempted to outline the entire system; which means that some of what follows may seem obvious and quite right, and some not at all obvious; or dead wrong. Many people have a tendency to complain about the State of the World, but to keep one part of it the part they are most dependent on immune to criticism; this is the part I urge you to look for, and to have patience with those chapters that you are sympathetic to or familiar with.

One final note. This book is largely based on the idea that there is no fundamental difference between the left and the right. I criticise both, and in order to do so I occasionally draw on leftist critique of the right, and vice versa. This does not mean that I support any other ideas, much less the entire philosophy, of the authors I quote or reference (or the publications they write for), with the possible exception of Snufkin.

iii. A Brief History of the System

Our society resembles the ultimate machine which I once saw in a New York toy shop. It was a metal casket which, when you touched a switch, snapped open to reveal a mechanical hand. Chromed fingers reached out for the lid, pulled it down, and locked it from the inside. It was a box; you expected to be able to take something out of it; yet all it contained was a mechanism for closing the cover.

Ivan Illich

For hundreds of thousands of years, people lived well in peaceful, egalitarian, healthy societies, at the very least in comparison with what followed. We did not work particularly hard and the work itself (if it could be called work; pre-civilised societies dont make distinctions between work and play), was enjoyable, meaningful and non-alienating. Activity is alienating if it makes you feel a stranger, or alien, to your own better nature, if you are forced to do it for someone elses profit, for example, or for no good reason, or if you dont feel at home with its results. For most of human history (actually pre-history properly speaking history begins with civilisation and writing) alienating work and ways of life were unknown; coercion and futility were inconceivable, as were property, religion, law, warfare, a great deal of superstition and what we could call mental illness. The fear of immediacy , when the senses sharpen to deal with danger in the present, was part of life because there has always been danger but fear of tomorrow , the profound and widespread care, anxiety, and worry that modern men and women are burdened with, was unknown.