STERLING and the distinctive Sterling logo are registered trademarks of Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

Illustration caption text 2016 Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (including electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without prior written permission from the publisher.

For information about custom editions, special sales, and premium and corporate purchases, please contact Sterling Special Sales at 800-805-5489 or .

Introduction

Philosophy has a long and exciting history. In some ways, however, it is an unusual history. In fields such as science, mathematics, medicine, and engineering, the major milestones can generally be viewed as unequivocal advances: stones are added to an ever-more-impressive edifice of knowledge. In philosophy, the milestones are more like insightful and thought-provoking comments in a Great Conversation. In this Conversation, one finds many fascinating insights and much food for thought, but not muchit must be admittedin the way of indisputable knowledge or agreement. To some, like controversial American editor and satirist H. L. Mencken (18801956), this is a sign of failure. Philosophy, said Mencken, consists largely of one philosopher arguing that all the others are jackasses. He usually proves it, and I should add that he also usually proves that he is one himself. There is some truth in this remark, for philosophy is, in large part, a story of vaulting ambitions and humbled reckonings. Philosophers have sought answers; what they have found are mostly questions. This in itself is highly instructive. As Socrates (c. 469399 BCE) vividly reminds us, a conversation that ends inconclusively can still be very much worth having. In philosophy, success is not measured in terms of clear-cut advances that can be added to a growing body of knowledge. Its successes lie largely in the questions themselves, and in the rich and vibrant conversations those questions can provoke as they become increasingly sophisticated and complex.

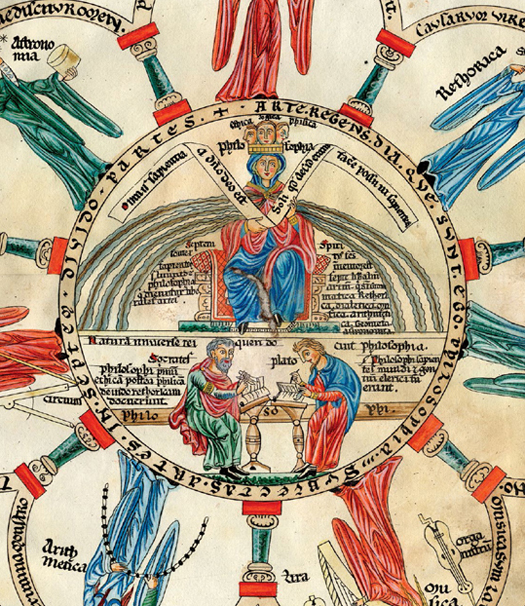

In brief, there is a special relationship between philosophy and its milestones. In philosophy, the milestones are not like buoys in a receding wake, never again to be seen as philosophers bravely sail on into uncharted new waters. Rather, the milestones are significant contributions to an ongoing conversation. In that discussion, great thinkers like Plato (c. 428c. 348 BCE), Aristotle (384322), Immanuel Kant (17241804), and David Hume (17111776) are not simply mute figures in a philosophical mausoleum; they are living voices in a fascinating dialogue that extends far into the past and will continue, one hopes, well into the future.

The Nature and Scope of Philosophy

What is philosophy? What are its proper tasks? These are themselves philosophical questions, open to debate. In early Greek philosophy, there was no clear distinction between philosophy and science. Philosophy was simply the love of wisdom, and it encompassed any field in which significant insights into the human condition and our world were believed to be found. Over time, the scope of philosophy progressively narrowed, culminating in the ultraminimalist view of some twentieth-century linguistic philosophers that philosophers are glorified lexicographers and concept analyzers, with no role to play other than as parsers and elucidators of language. Most contemporary philosophers adopt a view somewhere in the middle between these very broad and very narrow conceptions of the proper scope of philosophy.

Though philosophers often deal with issues that may seem quite technical and hairsplitting, at its core philosophy still deals with the big questions of life that exceed the ken of the physical and social sciences: Why am I here? Does life have meaning? Does God exist? Is there life after death? Can I know what true reality is? How should I live? What should my goals and values be? What is a good society? Philosophy remains most electric and vital when it remains in close contact with these big existential questions.

The Value of Philosophy

If philosophy is not, as I have suggested, a path to definite knowledge and assured ultimate truth, wherein lies its value? Its chief benefit is in the way it disciplines, enlarges, and humbles the human mind.

Philosophy disciplines the mind by introducing it to a regimen and a thought world in which standards of reasoning, argumentative rigor, clarity of expression, critical scrutiny, and logical coherence are much higher than they are in ordinary life. By means of this regimen, our powers of thinking, reasoning, and effective expression are greatly augmented, and we develop defenses against the nonsense and illogic that bombards us from the media, on the Internet, and in our daily lives.

Philosophy also enlarges the mind by expanding our intellectual horizons and exposing us to visions of reality and of the good life that we may never have thought without it. In philosophy we encounter (to adapt nineteenth-century British poet Matthew Arnolds phrase) the best that has been thought and said about questions of meaning, value, and the urgent existential questions of life. As we grapple with lifes mysteries, reading the great thinkers of the past can be of immense value. As American philosopher Tom Morris (b. 1952) has noted, these thinkers are like native guides who have thoroughly and skillfully explored territories that are all new to us. In studying the great philosophers, we can also achieve a better understanding of the important ideas and intellectual traditions that have shaped our world today.

Finally, philosophy humbles the mind by bringing home the depth, intricacy, and difficulty of the great questions. In many ways, the story of philosophy is a narrative of humbled ambitions. Time and again, great thinkers have claimed to discover ultimate truth, only to be shot down in flames. The lesson to be drawn from this is not that philosophy is a waste of time (Menckens view), but that philosophy is tough sledding and rarely can produce definitive answers beyond dispute. Realizing this is itself an important kind of wisdom.

Chronology and Principles of Selection

The milestones in this volume are significant ideas, events, and works in the history of philosophy. I have arranged these in chronological order, providing precise dates whenever possible, and approximate dates when precision is impossible. Since this is a book written for general readers, I have included some works (e.g., the Vedas [c. 1500 BCE], Ecclesiastes [c. 300 BCE], and Sigmund Freuds