School Culture Rewired

How to Define, Assess, and Transform It

Steve Gruenert and Todd Whitaker

Table of Contents

Publisher's note: This e-book has been formatted for viewing on e-reading devices. If you find some figures hard to read on your device, try viewing through the Kindle for PC (www.amazon.com/gp/kindle/pc) or Kindle for Mac (www.amazon.com/gp/kindle/mac) applications on your laptop or desktop computer.

ASCD 2015

Chapter 1

Defining Organizational Culture

....................

Have you ever noticed how service can vary from restaurant to restaurant? At some, you walk in and are greeted by a friendly, attractive host who whisks you away to an available table; at others, you can't get anyone to make eye contact with you, let alone greet you in a friendly way. Often, such a disparity can be found among restaurants that are part of the same chain! What is going on? How can two restaurants from the same company be so dramatically different?

Similar disparities can be found between and within schools and districts: You walk into some schools and immediately feel welcome; you walk into others and you feel like an intruder. In some schools, every teacher seems to be out from behind the desk, lessons are infused with technology, and students appear to be highly engaged in learning; in others, teachers seem to use their desks as fortresses and students appear distracted or disengaged. In both schools, teachers will tell you that what they're doing is effective.

Why is it that some schools embrace new ideas, while others consider them distractions? Why do some teachers roll up their sleeves, while others simply roll their eyes? More important, is there anything we can do to address these differences? Often, disparities within schools and districts are the result of separate cultures having been established over time. For schools to be effective, educators need to understand the organizational cultures in which they work and be able to modify them if necessary.

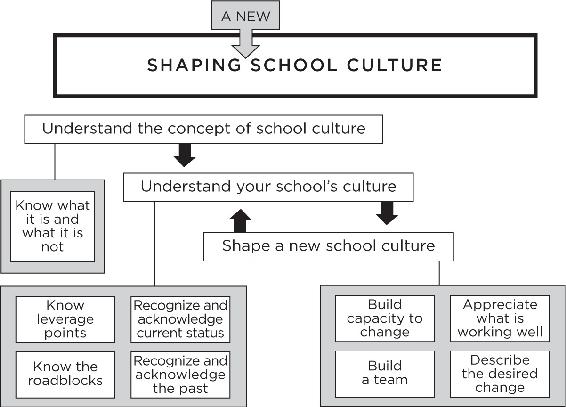

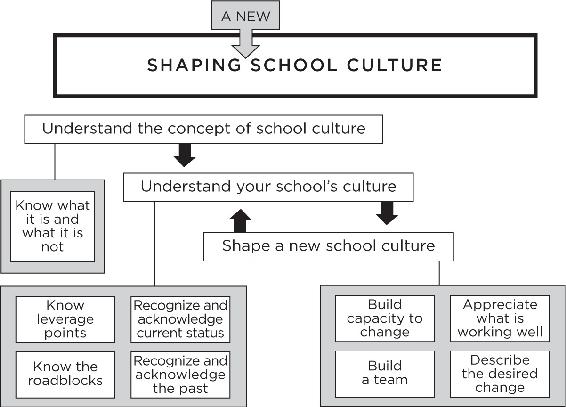

Understanding an Elusive Concept

This book is intended to help you better understand the general concept of school culture, learn the strengths and weaknesses of your specific school culture, andperhaps most importantinfluence your school culture or, if necessary, shape a new one (see Figure 1.1). In the following pages, you'll learn what to do, what to expect, and what positive and negative signs to look out for when trying to improve your school's culture.

Fig 1.1 The Keys to Shaping a New School Culture

To improve your school culture, you must dig deep into the psyche of your organization and figure out why certain actions or attitudes are entrenched. Often, such actions or attitudes are actually rewarded by a school's culture, so any desirable new behaviors will need to be rewarded by the culture as well if they are to be sustained. Indeed, the effect of school culture on teacher and student behaviors cannot be understated.

You may be thinking, But surely people choose what to do in every situationit's not as though we're robots programmed to act a certain way when we arrive at school, right? The fact is, the whole purpose of a school culture is to get members to adopt predictable behaviors and a common mental model. Culture is both a survival mechanism and a framework for solving problems. If every member of a group agrees to fulfill a certain role within the group, then the group has a better chance of surviving. If some members stray from their roles, the group becomes weak; if many stray or even defect from the group, the group becomes vulnerable to takeover. In the context of schools, a takeover could mean the ascension of a new leader who is not very effective. So, yesin a sense, culture is , as Hofstede put it, a "collective programming of the mind which distinguishes the members of one organization from another" (1997, p. 180). Cultural programming even provides members with virus protection in the form of immunity from external influence. To a culture, any change is a virus.

The effectiveness of a new culture depends on the strength of the people behind the change and the strength of the pre-existing culture. For example, imagine that a new, charismatic leader arrives at a school with a weak pre-existing culture lacking cohesiveness. Using a few persuasive tricks to hook teachers emotionally, such a leader might convince the faculty to gel around his or her values, which eventually will freeze into a school culture (Lewin, 1951). If the leader is sufficiently charismatic, the new culture might become strong and difficult to changebad news if his or her values are misguided or counterproductive. However, if you and your colleagues have a real understanding of what a school culture is, you'll be a lot less likely to let a misguided leader take over your school.

The effectiveness of a new culture depends on the strength of the people behind the change and the strength of the pre-existing culture.

Look around youthe call for accountability has brought an urgency to schools that feels more like panic. Educators have been convinced that they're doing a poor job and have been sold the idea that they'll benefit from leadership informed by business practices. As the line of ineffective corporate leaders gets longer, MBAs who can't achieve success in the corporate world are increasingly entering the field of education, but this is hardly ever a good fit. The culture of schools, like the culture of churches or community centers, is a world away from the culture of Big Business. Whereas churches and community centers are usually nonprofit organizations that provide desired services to the local population, corporations seek beyond all else to make a profit. Which of these two missions better represents what schools should hope to do?

How the Experts Define Culture

Edgar Schein, Geert Hofstede, Clifford Geertz, Terry Deal, and Allen Kennedy are just a few of the major names in the study of organizational culture, which has its roots in the field of sociology. Geertz has noted that culture "is not a part of experimental science in search of laws but an interpretive one in search of meaning" (Geertz, 1973, p. 5). Culture is not a problem that needs to be solved, but rather a framework that a group can use to solve problems; it is how we learn to survive, one generation passing down what it has learned to the next. Culture is essentially a social indoctrination of unwritten rules that people learn as they try to fit in a particular group (Schein, 1992). It's also been referred to at different times as any of the following:

- The social glue that holds people together

- "The way we do things around here"

- Activity behind the scenes or between the lines

- What's really going on

- The patterns of behavior that distinguish us from them

- An invisible force-field that limits actions and thoughts

- A set of behaviors that seem strange to new employees

- Deeply embedded beliefs and assumptions

- The unwritten rules

- Software for the mind

- A home-court feeling

- The default mode of behavior

- Covert assimilation (that feels like accommodation)

- A collective consciousness

- Shared social reflexes