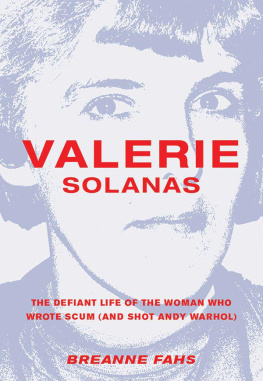

SCUM MANIFESTO

VALERIE SOLANAS

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY AVITAL RONNELL

This paperback edition published by Verso 2015

This Verso edition first published 2004

Introduction Avital Ronell 2004, 2015

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay St, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-440-9

eISBN-13: 978-1-78478-442-3 (US)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78478-441-6 (UK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Solanas, Valerie

SCUM manifesto. New ed.

1. Women Social conditions 2. Sex role 3. Men Psychology

I. Title

305.4 2

The Library of Congress Has Cataloged the Hardcover Edition as Follows:

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Solanas, Valerie.

SCUM manifesto / Valerie Solanas ; introduction by Avital Ronell.

p. cm.

Originally published: London : Olympia Press, 1971.

ISBN 1-85984-553-3 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Sex role. 2. Sex differences (Psychology) 3. Men. 4. Misandry.

I. Title.

HQ1075.S592 2004

305.3--dc22

2003027103

Typeset in Berthold Baskerville

Printed in the USA by Maple Press

CONTENTS

DEVIANT PAYBACK: The Aims of Valerie Solanas

Avital Ronell

SCUM MANIFESTO

Valerie Solanas

DEVIANT PAYBACK:

THE AIMS OF VALERIE SOLANAS

In 1968 Jacques Derrida brought out his pathbreaking essay, The Ends of Man, and Valerie Solanas began earnestly distributing SCUM Manifesto. In June of that year she gunned down Andy Warhol as he was speaking on the telephone. These events may seem miles apart on the cultural shock charts, yet they are linked in ways that urge us to reflect on their ineluctable contiguities. Both Derrida and Solanas are interested in the aims and finality of the concept man. Admittedly, that may be where their improbable rendezvous ends, somewhere on an existential corner of 1968, situated among the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr., Fred Hampton, and Bobby Kennedy, at the moment they shared the beat of a feverishly agitated Zeitgeist. This was the moment in any case when man, getting a political pounding, was up against the philosophical wall and steadily losing ground. Derrida, conceptually fitted for the job, was concerned with the excess of man, which Solanas, we could say, enacted. Where he exposed the Greek ideal of anthropos, she went for the jugular of referential man, busting through layers of philosophical history to put out her own ends of man, her own limit case of the classical unity of man.

More than anything else, Valerie Solanas wanted to be a writer. When she couldnt distribute her work, she went after metonymies of her declared targets. But now I am shooting off too rapidly. Let us back down in order to get a sense of Valerie Solanas and the nonplace that she rigorously occupies. Barely representable or representative, she was a speck and spectre on the margins of extremist writing. Her texts were loaded with irony yet pointed at the real. Confined to the precincts of parasitical utterance, she adopted the language of a pest, plugging the kind of speech that counters while resembling hate speech. Strangely, she was meant to ride the dark side of a fore-closive wave, opening up a field of startling intensities by saying the unspeakable and then vanishing with the near notarization of what she had dared to say. She was on the verge of instituting her sexual hermeneutics, at least in terms of language games. But Solanas was not about to acknowledge her part or participation in any male-driven language game. Perhaps it would be helpful to allow that she had positioned herself on the other side of hate speech. When launching a verbal assault she struck where no terror had been located. Or, the terror against which she set up her linguistic shop had not been heeded, addressed. Not even recognized: Most philosophers, not quite so cowardly [as most men], face the fact that male lacks exist in men, but still cant face the fact that they exist in men only. So they label the male condition the Human Condition; pose their nothingness problem, which horrifies them, as a philosophical dilemma (53).

So. Sometimes you have to scream to be heard. This is what Heidegger says regarding Nietzsche in What Is Called Thinking? Other quasi-linguistic worlds open up in this space, springing from the noncanonized tropes of moaning and bitching. Few would want to scan the realm of garbled language games.

Scouring the hetero-rhetorical unconscious of the social milieux through which she ventured, Valerie Solanas found herself disabled by the very fact of language, by its phallic lures and political usages, by its disturbing record in the human sciences and liberal arts by the mere fact of its incessant institutional collaborations. Maybe she exploited the failed performative for all its worth, knowing all along that failure was a matter only of degree. Who, besides the occasional psychoanalyst, imagined themselves not to fail in the domain of fateful utterance? Judith Butler has devoted the book, Excitable Speech, to a wide range of linguistic vulnerabilities. At one point she explains the stakes besetting one who tries to hit a linguistic target. When I say, I condemn you, Butler writes, should I not be in a position to have my words considered as binding[;] then I may well have uttered a speech act, but the act is in Austins sense, unhappy or infelicitous: you escape unscathed. In some ways, Solanas shows up as a victim of the failed performative, as one who felt her verbal velocities could reach no one in a way that would truly mark or unhinge the brutal protocols of lived reality. At the same time, Valerie Solanas, who took no prisoners, took pleasure in the injurious effects of language and, with Lacanian precision, understood that words are bodies that can be hurled at the other, they can land in the psyche or explode in the soma. A hurtful utterance can give you hives, make you want to throw up, put a dent in your appetite, or summon up any number of somatic responses and physical collapses.

Tripping over the pitfalls that await any speech act, the Manifesto nonetheless seeks to make itself binding; the fervent hope that we would be bound by its effects appears to indicate the scope of its dilemma. Valerie wanted to draw a contract, the urgency of which was to be impressed upon any number of potential signatories. She took her petition, her social contract, to the streets something Rousseau had done when he was cooking up his revolution. Like all social contracts, it had an anti-social edge. But this was different, to say the least, though it participated in the destructive demands of prior manifestos. One thinks of the Futurist Manifesto with its uncringing attack on women: We will glorify war the worlds only hygiene militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for woman We will destroy feminism. Maybe the Solanas tract was payback; it was clocked to strike the time of response to all shameless woman-hating manifestos and their counterparts, the universalizers. No matter how you cut it, universal whether common or communist meant man. Solanas was intent on ending it and tightening the noose around the finitude of man.