Did you know that

- learning can result in either an increase or a decrease in responding?

- learning may not be readily apparent in the actions of an organism? Special test procedures may be required to see evidence of learning.

- learning may be investigated at the level of behavior, neural circuits and neurotransmitter systems, or individual neurons and their synapses?

- learning is a cause of behavior change? Therefore, learning can only be investigated with experimental methods that identify causal variables.

- control procedures are as important in studies of learning as training or experimental procedures?

L earning is of great interest because it is the primary means by which organisms make long-term adjustments in their behavior so as to become better attuned to the world in which they live. Learning requires flexibility in how one responds to the environment and therefore was considered evidence of intelligence by Darwin and other early comparative psychologists (Darwin, 1897; Romanes, 1882). Contemporary scientists study learning to gain insights into how the mechanisms of behavior are altered by experience. Learning procedures are often used in studies of clinical, developmental, and cognitive psychology, as well as behavioral neuroscience and psychopharmacology.

Learning is a pervasive feature of human behavior and is evident in many other animal species as well. It has been found in creatures as diverse as fruit flies, sea slugs, honeybees, rodents, birds, and monkeys. Thus, learning is one of the fundamental characteristics of behavior.

Fundamental Features of Learning

People learn to recognize friends as different from strangers. They learn how to hold a telephone and how to answer it when it rings or vibrates. They also learn to swim, to ride a bicycle, and to avoid stepping in potholes. In all of these cases, learning is identified by a change in behavior. An experienced swimmer or cyclist behaves very differently from someone who has not learned to swim or ride a bike.

Learning to swim or ride a bicycle involves learning new hand, leg, and body movements and coordinating these movements to achieve balance and forward locomotion. Many, but not all, instances of learning involve the acquisition of new responses. We also learn to not do certain things. Children learn to keep quiet in church, to hold still when being examined by a doctor, and to not run into the street without first looking to see if it is safe. Learning to inhibit or suppress behavior is often as important as learning new responses. Riding a bicycle, for example, requires learning to pedal as well as learning not to lean too much to one side or the other. Thus, the change in behavior that is used to identify learning can be either an increase or a decrease in a particular response.

LEARNING AND OTHER FORMS OF BEHAVIOR CHANGE

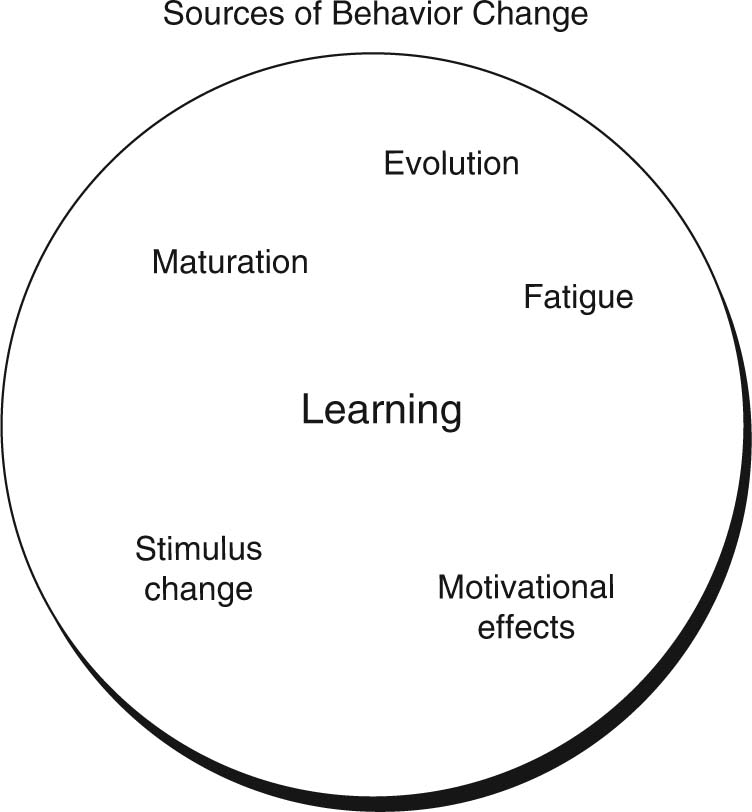

Although all learning is identified by some kind of change in behavior, not all instances in which behavior is altered are instances of learning (see ). Therefore, it is important to distinguish learning from other sources of behavior change.

FIGURE 1.1

Possible mechanisms that can result in changes in behavior. Note that learning is only one of several possible sources of behavior change.

A major feature of learning that makes it different from other forms of behavior change is that learning is relatively long lasting. This serves to distinguish learning from various short-term or temporary changes in behavior. Fatigue and drowsiness can cause widespread and large changes in behavior (many of your actions become slower and less vigorous). However, such changes are temporary and can be reversed by a good rest. Major short-term changes in behavior can also be caused by changes in motivation. For example, people are much more reactive to stimuli related to food when they are hungry than after a hearty meal. Changes in stimulus conditions can also cause widespread but short-term changes in behavior. If you get a stone in your shoe, the discomfort is likely to change the way you walk and may encourage you to stop and empty your shoe. But the disruption is likely to be short lasting; you will resume your usual gait once the stone is removed. Learning, by contrast, involves longer term changes. The assumption is that once something is learned, it will be remembered for a substantial period of time. For example, you are not considered to have learned a new concept discussed in class if you cannot remember it the next day.

Although learning involves enduring changes in behavior, not all long-term changes are due to learning. Long-term changes in behavior can also be produced by physical growth or maturation. Children become more skillful in lifting heavy objects and reaching a cookie jar on a high shelf as they get older. These changes result from physical growth and maturation rather than learning.

Behavioral changes due to learning and changes due to maturation can be interrelated and difficult to distinguish. As a child becomes stronger and taller with age, these maturational changes facilitate the learning of new skills. However, one important difference between learning and maturation is that maturation does not require practice with things specifically related to the skill that is being acquired. A child will become better able to reach high shelves as she gets older whether or not she ever practices reaching for cookies. Practice is not needed for maturation, but it is required for learning.

Practice is obviously necessary to learn a skill such as swimming or riding a bicycle. One cannot become an expert bicycle rider without extensive practice with pedaling, steering, and balancing. Other things can be learned very quickly. A child will learn not to touch a burning log in a fireplace after just one painful encounter. Regardless of the amount of practice involved, however, all learning requires some practice or experience specifically related to the acquired behavior.

Another difference between maturation and learning is that the same maturational process can produce behavioral changes in a variety of situations. As a child grows taller, she will be able to reach taller shelves, climb taller trees, and catch butterflies that are flying higher off the ground. In contrast, behavior changes due to learning are more limited to the practiced response. Learning to operate a kitchen stove will help you cook indoors but will not improve your skill in building a fire for cooking on a camping trip. This is not to say that learning about one thing cannot help you do something else. Some generalization of learning can occur. However, generalization of learning tends to be limited. What you learn in one situation only generalizes to other similar situations. For example, learning to operate a particular gas stove will improve your ability to work other similar stoves but may not help if you are trying to cook with a microwave oven.

Another type of long-term change that has to be distinguished from learning is change due to evolution. Evolution can change not only the physical attributes of organisms but also their behavior. Furthermore, evolutionary changes, like learning, are a result of interactions with the environment. However, evolutionary changes occur across generations. In contrast, learning creates changes in behavior much more quickly within the lifetime of an individual organism.