INTRODUCTION

BY MARK MACKENZIE

The best travel writing evokes not just a sense of place, or of wonder, but relates its story with a distinctive voice. Unsurprisingly, the authors collected here are nothing if not observant. Classics of the genre are more than the sum of their parts, revealing not simply the where and when, but the extent to which the author was changed by a particular destination, or vice versa. The soaring prose of Robert Byron, for example, whose descriptions of the architectural splendours of Isfahan show a young man in the throes of revelation. Or the coruscating wit of DH Lawrence, complaining his way around Sardinia and by so doing confirming the bitterness of exile. Washington Irving, in contrast, waxed so lyrical about the Alhambra, in Granada, that his account did much to save it from absolute ruin.

The books selected have inspired countless travellers and writers, in some cases explicitly. Mary Wollstonecrafts portrayal of the brooding Norwegian scenery directly informed the landscape of Frankenstein, the Gothic novel penned by her daughter, Mary Shelley. Later, the richly poetic nature writing of John Muir helped give rise to the American conservation movement.

Social attitudes have, of course, changed. Dominions no longer need civilising; natives have gods of their own. Some of the travellers featured here, judged by modern standards, seem driven by little more than vanity; witness Theodore Roosevelt crashing through the Brazilian wilds, self-appointed saviour of Amazonian tribes. Or Jack London, sailing not quite around the globe in a boat sufficiently small enough to endorse his own ideas about machismo. It might be argued that any form of travel is some form of indulgence, yet what redeems them is both the quality of their writing and the extent to which each became a force for good; Roosevelts expedition shone an early light on the fragility of the rainforests, while Londons visit to a Hawaiian leper colony helped change attitudes to the disease. And those works that tell of landscapes lost, such as Mark Twains Life on the Mississippi, or Margaret Fullers Summer on the Lakes, serve as salutary reminders of the consequences of progress.

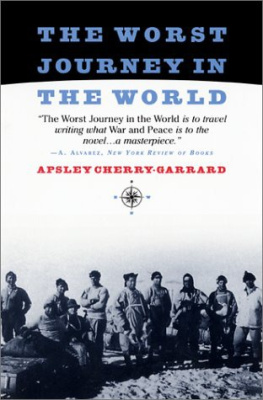

Then there are the pure explorers. Held alongside great stylists, such as Lawrence or Twain, accounts of Fridtjof Nansens bid to be first to the north pole, or Ernest Shackletons similar ambition for Antarctica, might seem destined to pale by comparison. Yet the strength of will to record even perfunctory details while under extreme physical duress and the subsequent effort to shape them into a compelling narrative has its own virtues.

Part of the explorers motivation, of course, is to be seen as a pioneer, and it is worthwhile to pause and reflect whose voices made it onto the record of the early history of travel writing. Again and again it is the adventuring Western imperialist whose reaction to new lands is recorded, whether they are surveying places newly subjugated, as Samuel Johnson does in the Hebrides, or purposefully bringing outside religion to another culture, as David Livingstone does. Occasionally it is a woman, but inevitably she is of a wealthy class, able to indulge in leisure travel, albeit representing an independent spirit that set an example for later generations. In almost all cases, the intrusion is not an invited one. We can appreciate the glimpse into long-gone scenes and simultaneously question the underlying motives of the observer.

A collection such as this should also be notable for its contrasts. So, alongside travels of great historical importance, such as Herodotus wandering through the Greco-Persian wars, you will find adventures less epic. Edith Wharton, long before she became the great woman of American letters, toured Morocco with a discerning eye for architectural detail. Robert Louis Stevenson, meanwhile, keen to take his mind off relationship problems, trotted alongside a donkey through the mountains of France. Both write about their travels with such distinction that at no point do their undertakings feel trivial; in fact, quite the opposite. Perhaps all that needs to be said is that the very finest travel writing, such as Henry James descriptions of the foggy bustle of London, elevates the everyday to the sublime.

MARY ANNE BARKER

INTRODUCTION

Mary Anne Barkers Station Life in New Zealand, published in 1870, recounts a three-year stay during which the author and her husband hoped to establish a sheep farm. The husband in question, her second, was Frederick Napier Broome, a British administrator who gave his name to Broome in Western Australia.

Lady Mary Anne Barkers pen name and title were a consequence of her first husband, Sir George Robert Barker. A British brigadier, Mr Barker had served with distinction at the Siege of Lucknow in India in 1857, for which he was knighted. Finding it commercially useful, Mary Anne retained the name, under which she published more than 22 books. Station Life in New Zealand, a collection of letters home to her sister, Jessie Stewart, was by some margin the most successful, reprinted in several editions and translated into a number of languages.

The Broomes travelled to New Zealand from England in 1865, following the purchase of a homestead, Steventon, on the Selwyn River. Mary Anne was a child of Empire (her father, Walter Stewart, had been Island Secretary of Jamaica), an advocate of both civilising Britains dominions and seizing the opportunities they presented. Station Life was intended to convey the simple pleasures, and challenges, of homemaking, writ large across the colonial landscape. Prior to their arrival, the Broomes had commissioned new stonework and timbers to improve the house, and which were brought from Christchurch. It seems wonderful that so expensive and difficult an engineering work, Barker wrote, could be undertaken by such an infant colony.

Steventon already had literary connections. The vendors, brothers Arthur and Richard Knight, were great-nephews of Jane Austen. (The farm was named after the Hampshire village where Austen grew up.) The Broomes were to oversee renovations personally and in April 1866 moved in, with the house still under construction. We hurried here as soon as ever we could get into the house, Barker noted, and whilst the carpenters were still in it. Barker was heavily pregnant, and wished desperately for the baby to be born in the house. The occasion duly arrived but the child, a boy, died shortly after. No doubt there are bright and happy days in store for us yet, Barker wrote, but these first ones here have been sadly darkened by this shadow of death.

The popularity of the book lay in Barkers depiction of everyday life. The books most well-known passage, featured in the extract here, concerns the weather. The Barkers had the misfortune to be lambing during the winter of 1867 when, in July, a freak storm hit.

The snow began on 29 July and lasted for a week. Completely cut off even the dogs needed digging out from their kennels the Barkers only food was two chickens. These they shared between the entire household, including dogs and farmhands. When the snow eased, they went in search of the sheep. Fearing the worst, their shepherd urged Barker not to come. What they found makes for grim reading, thousands of animals either frozen to death or drowned when meltwater flooded the gullies in which they had taken shelter.

Barkers account of the storm became an important social document, in part because other witnesses, notably the local Mori whom Barker claims prophesied the storm, passed on the event as oral history. Whenever New Zealand experiences similarly extreme weather, for example in 1939 and 2010, Barkers account is invariably referenced.