A T RAVELLERS Y EAR

A T RAVELLERS Y EAR

C ONTENTS

C ONTENTS

E very single day of our lives we embark on different journeys. Those journeys can sometimes feel more metaphorical than literal. But even the most boringly habitual of commutes can be subject to the wildest of variations. An unexpected delay or diversion can take us far from our intended destinations, or make us look afresh at our everyday routes and surroundings. A trip to the corner shop can prove as surprising as a distant land. And perhaps in an age when Google Maps and a mobile phone put the ends of the earth at our fingertips, and we are rightly concerned about our carbon footprints and airport security, it is good to remember that travelling lightly and locally can be just as enriching as ranging far and wide.

Travel, though, is the great broadener of the mind, if sometimes also a thinner of the wallet. Once acquired, the wanderlust is hard to shake off. A backpack or a suitcase and a plane, train, boat or bus ticket, can be a bridge to a wealth of new experiences. We are wiser for encountering more of the planet, no matter how fleeting our personal visits to its less familiar parts might be. The problem, arguably, for the twenty-first-century voyager, in a globalized, corporatized and Internet-enabled world, is perhaps finding the truly unfamiliar. That problem is, nevertheless, frequently and wildly overstated. The world, fortunately, continues to be dizzyingly diverse. And, in any case, complaints much like this recur throughout the annals of travel literature.

It is over thirty years since the great John Julius Norwich maintained that cheap air fares had made it all but impossible to be a traveller. Tourism, to his mind, had triumphed, and the old romance of travel was gone; the world had become a remarkably small one and the whole thing... too easy, too run-of-the-mill. D.H. Lawrence, one of the contributors to this anthology, had made virtually the same point back in 1931, gripingfrom New Mexico that there was no mystery left in travel and that tourists now went around the poor little globe as easily as they trotted round the Bois, or round Central Park. Compiling this volume, however, we have found that complaints about tourists have existed for almost as long as people have been travelling.

One of our aims with A Travellers Year a book that invites the reader to head off on fresh excursions each and every day of the year was to give a real flavour of the world when it was sketchily mapped. Until only fairly recently we must remember that a journey of just a few hundred miles could be difficult, uncomfortable in the extreme and frequently dangerous. For centuries, horse and wind powered a globe whose vehicles were made mostly of wood and were commonly infested with rats and prone to sinking or catching fire. The stars above and the sextant and the compass reigned supreme in navigation. GPS and sat nav would appear the stuff of witchcraft to many of these sailing ship-borne explorers, for whom steam power or an iron-hulled liner was as unknown, and unfeasible, as the idea of Australia. In seeking to extend the bounds of human knowledge and usually also the reach of some imperial territorial gain, even final destinations might be vague. Such journeys, like those made by Christopher Columbus, beyond lines on existing charts, quite possibly marked simply Here be Dragons, were undertaken in hope, with routes followed as much a matter of guesswork and luck as expertise. The chances of reaching wherever there was let alone getting back home alive was limited. And even a cursory glance at the fates of several of our diary and journal writers, men like Mungo Park, Captain Cook, John Franklin and Robert Falcon Scott, who met their ends at sea, in the field and on the ice, only confirms what a risky business travel could once be.

Of course, the so-called Golden Age of Exploration, if heroic and romantic, can feel slightly remote to us today. To the modern traveller, many of its colonial assumptions, like its weevil-riddled rations, appear unpalatable, if not utterly repellent. By contrast, its striking how contemporary the diaries, letters and journals left to us by those who undertook Grand Tours of Europe or further afield can seem. Naturally, they bring a fair bit of baggage with them too. Dubious national stereotypes and outright prejudices abound. In the case of most British visitors to the Continent during this period, and some time beyond, only Count Dracula could possess a greater fear of garlicky food. And, on occasions, also bright sunlight. But reading first-hand accounts of uncomfortable beds, poorservice, and inadequate meals in inns and hotels from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, we were regularly put in mind of reviews wed seen on TripAdvisor or similar websites.

We were nevertheless conscious that until well into the twentieth century, travel for its own sake largely remained the preserve of the most affluent. They were, quite obviously, the only people with the means and the leisure to embark on such supposedly self-improving or health-bringing sojourns to Florence, Rome, Egypt or the Holy Land, Tangiers, Marrakech or wherever. (Or if you were Queen Victoria, had access to a fully crewed Royal Yacht, and are suddenly gripped by an urge to sail about Scotland.) Correspondingly, it is mostly, if not exclusively, their journals that found publishers at the time or were subsequently preserved for posterity. Where possible, therefore, we have tried to include extracts from less-well-heeled travellers to ensure as much variety as possible, along with at least some impressions of Europe from those visiting it from outside as a foil to all the western reports of Asia, Africa and the Middle East.

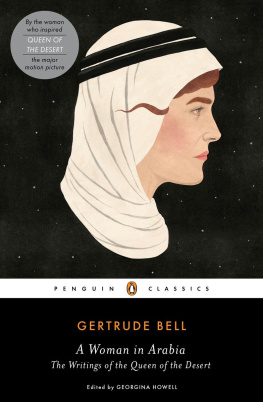

Travel writing has a long and distinguished history. Its tropes are present in the earliest works of the English literary imagination from Chaucer and Bunyan to Swift and Defoe, and in the Victorian era travel books were still among the most widely read, behind novels and romances but easily ahead of biographies and histories. In the following century not only did some of the finest novelists from Graham Greene to Evelyn Waugh pen accounts of their travels, but writers like Robert Byron, Peter Fleming, Dervla Murphy, Patrick Leigh-Fermor, Wilfred Thesiger and Bruce Chatwin breathed new life into the form. You will encounter material from all of these titans of travel in this anthology. But our commitment to the immediacy and intimacy of the dated diary or journal entries means that some familiar names in the genre are missing, while other much more obscure scribblers enjoy a prominence here denied to them previously.

Here, though, we believe, is an astounding journey, a book hopefully the equal of any package deal dreamt up by Thomas Cook. For A Travellers Year is intended as an odyssey around the globe, moving from day to day and back and forth through five centuries of travel in the company of explorers, missionaries, pilgrims, foot soldiers, ordinary seamen, pioneers, colonists, botanists, diplomats, aristocrats, artists, writers, poets, playwrights, dilettantes, free thinkers, early feminists, thrill-seekers, adventurers, bloggers, rock musicians, an air hostess and cheap-seat-relishing gadflies.

Next page

A T RAVELLERS Y EAR

A T RAVELLERS Y EAR