Contents

About the Book

Parks are such a familiar part of everyday life. You might be forgiven for thinking they have always been there and that they always will.

In fact, the roots of even the most humble neighbourhood park lie in age-old battles over land and liberty. From their medieval life as private royal hunting grounds to their modern incarnation as public spaces teeming with activity, theirs is a story of land-grabbing monarchs and Restoration fops, great Victorian industrialist, punks and model-boaters and somewhere among it all, the common man trying to enjoy his single day of rest.

In the company of Travis Elborough, we meet this colourful cast, explore the archives, take the occasional hop across the Atlantic and the Channel, and learn the stories wthat will have your next trip to the park brimming with anecdote and new meaning. We learn, too, that in an era of cuts, Britains parks are under threat. As such, this vibrant, loving history is a timely celebration of a small wonder that we may on occasion take for granted.

About the Author

Travis Elborough is the author of four acclaimed books, The Bus We Loved, a history of the Routemaster bus; The Long Player Goodbye, which lamented the passing of vinyl; Wish You Were Here, a history of the British beside the seaside; and London Bridge in America, which tells the transatlantic story of the sale of the world's largest antique. Travis regularly appears on Radio 4 and writes for the Guardian.

Also by Travis Elborough

The Bus We Loved: Londons Affair With the Routemaster

The Long Player Goodbye: The Album from Vinyl to iPod and Back Again

Wish You Were Here: England on Sea

London Bridge in America: The Tall Story of a Transatlantic Crossing

For my parents and in

reminiscence of afternoons

spent on Sompting Rec

Introduction

The Swiss author Robert Walser once argued that it always feels like a Sunday in a park. Like Sundays, parks certainly occupy a unique temporal zone. For their visitors at least, they seem at one remove from workaday life. Time within them can be wasted, parks supplying the ideal location when weve nothing else to do. Or desperately want to do nothing in particular, and as languorously as possible. And yet they are also hives of activity albeit of a leisurely, if athletic, kind.

When Walser spoke of Sundays, though, it was because, for him, these public spaces were imbued with the same melancholy as the interminable Sundays you only ever experience as a small child. Perhaps Walsers melancholy is unique, but the park, for many of us, is surely infused with childhood memories: of lazy sun-dappled afternoons, of swings and roundabouts, and mud-stained knees on the local playing fields, the aroma of freshly mown grass and the cloying scent of brightly coloured geraniums. Nearly all of us first encounter parks as small children. And, in due course, take our own children to parks. So maybe some of us do share Walsers melancholy perhaps these spaces remind us of lost innocence and the passing of the years.

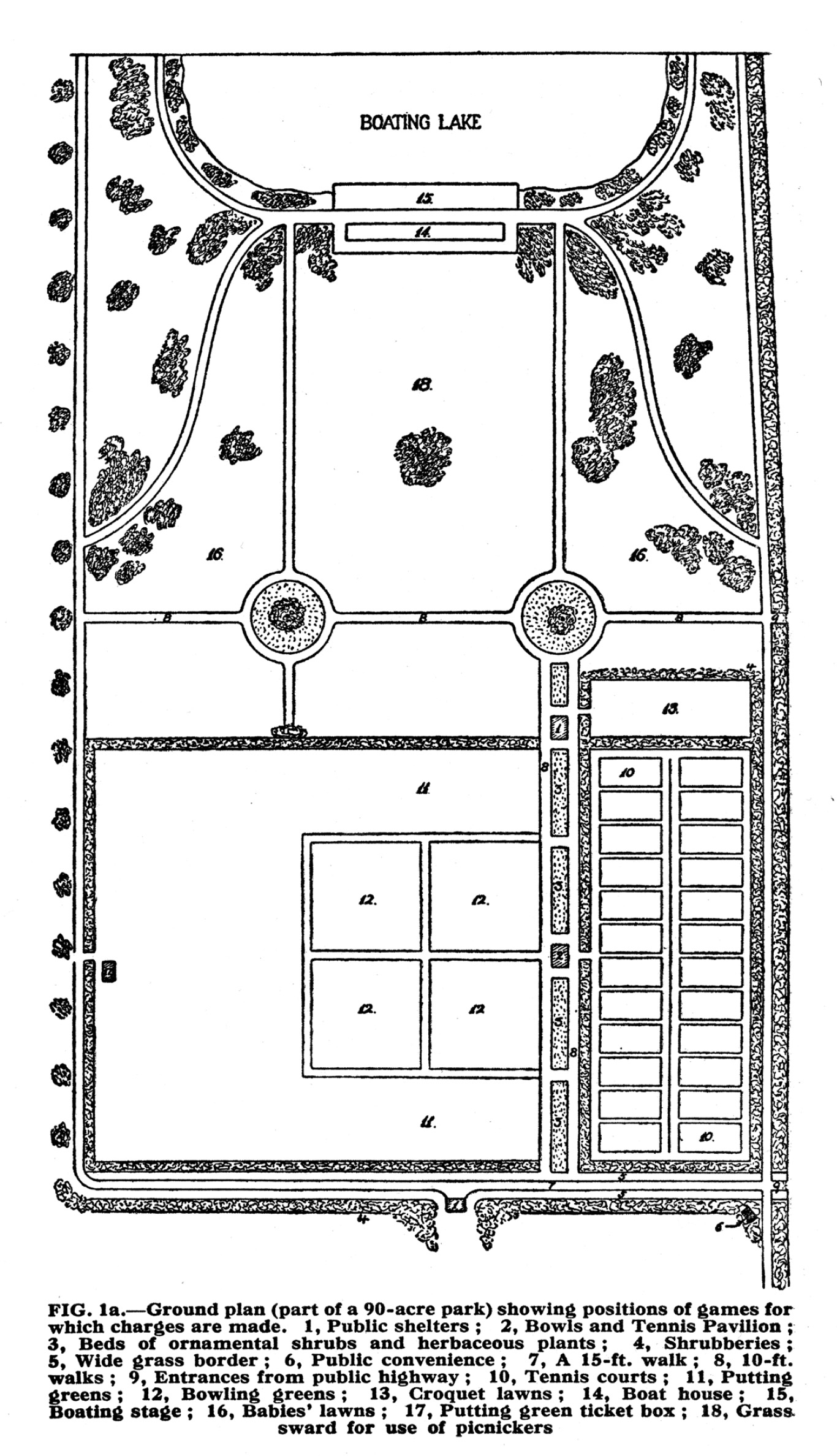

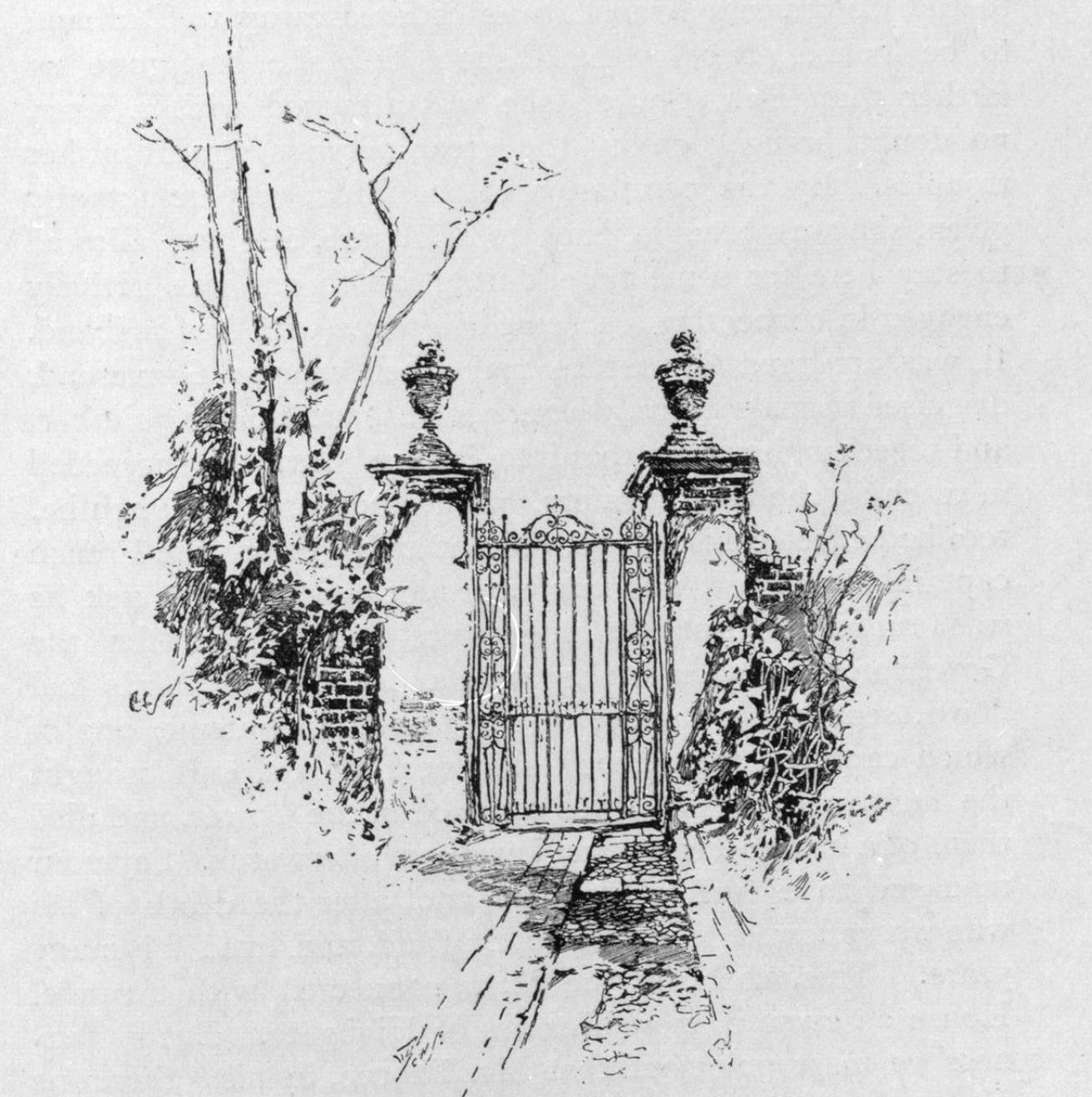

When it comes to space rather than time, the limits of the majority of public parks remain clearly demarcated by fences and gates. Such barriers are seemingly there to protect the park from the noise and mess of the town or city. Or vice versa, with the metropolis quite possibly fearing contamination from too much exposure to plants and grass, much like a small child forever nudging uneaten vegetables to the edge of their dinner plate. But these barriers also create an aura of expectation, crowning the park as a precious destination in its own right, one that takes us out of the humdrum streets surrounding it, and out of ourselves. For grander public parks, there are postcards to send and collect, as if they were far-flung and exotic locations. To orientate ourselves in these places we consult their maps as eagerly as sailors, back in the day, staved off scurvy with sauerkraut and peered at the horizon with a sextant in hope of land. And like other newly discovered worlds, their founding principles were on occasion utopian, if, in retrospect, no less naive, misguided, presumptuous and plain wrong.

And this is a crucial point. Public parks were indeed founded, or to escape the metaphor, and put it plainly invented. General access to tended green spaces and the ability to enjoy them at relative leisure are comparatively modern and hard-fought developments, and the roots of even the humblest neighbourhood park or recreation ground lie in age-old battles over land and liberty. In Britain and much of the developed world, historically very little land was ever truly public. Under feudal systems, all land was essentially the property of the King, and access to it granted directly by the Crown or via feudal lords. Common law in Britain meant that there were such things as commons, where the public might, for instance, graze cattle. But this space was not at all sacred, and was frequently enclosed by royalty and landlords for their private pleasure.

This trend continued right up until the opening decades of the nineteenth century, as British monarchs remained unstinting in snaffling previously accessible land and adding it to their store of greenery. Charles I, for instance, had blocked off several local footpaths and removed acres of parish grazing ground when he walled in Richmond Park in the 1630s. It was 1904 before the public got full access to the park again. And it was only the vigilance of Robert Walpole, Britains de facto first Prime Minister, that prevented Queen Caroline from seizing the whole of St Jamess Park as her personal garden. While George IVs Regents Park which casually absorbed areas of smallholding farmland used to grow hay for Londons horses was developed as a money-making scheme for the Crown, with exclusive residential properties incorporated into what was a gated private park.

As well see, the creation of public parks wasnt a sudden thing. The first parks were private, and, more often than not, used as royal hunting grounds. But over time it became apparent to some enlightened souls that an unhappy, subjugated population would benefit from designated public green space. And so would their rulers. Indeed, many of the globes most famous public parks were created in part to quell political unrest and prevent revolutions. Parks are, of course, tamed wildernesses. And as the world became farmed and then industrialised and consequently less wild, ecologically speaking, parks were widely deployed as tools to tame supposed wildness among the population, ease alienation and see off social discord.

But cultivated wildness can unexpectedly cultivate wildness, and much as rebellious peasants had once conspired to steal game from royal preserves, so disaffected urbanites would consistently use the park as a place to gather to misbehave, often disgracefully, and forcefully challenge authority.