1BYKADA ORPHANAGE

2ARNOWIEC NUCLEAR POWER PLANT

3PYRAMIDEN

4THE CASTLE OF DONA CHICA

5SANS-SOUCI PALACE

6RUBJERG KNUDE LIGHTHOUSE

7SAMMEZZANO CASTLE

8WNSDORF

9OLD AL-ULA

10MANDU

11CRACO

12GRNGESBERG

13PLYMOUTH

14KOLMANSKOP

15KENNECOTT

16DLLERSHEIM

17THE WEST PIER

18SANTA CLAUS

19DUCOR PALACE HOTEL

20HACHIJO ROYAL HOTEL

21GRAND HTEL DE LA FORT

22CAMELOT THEME PARK

23THE SALTON SEA RIVIERA

24NEW WORLD MALL

25KUPARI

26HELLINIKON OLYMPIC COMPLEX

27NICOSIA AIRPORT

28UYUNI TRAIN GRAVEYARD

29CRYSTAL PALACE SUBWAY

30SUAKIN

31CITY HALL SUBWAY STATION

32BALAKLAVA SUBMARINE BASE

33ST PETERS SEMINARY COLLEGE

34ROOSEVELT ISLAND SMALLPOX HOSPITAL

35VOLTERRA PSYCHIATRIC HOSPITAL

36GARY CITY METHODIST CHURCH

37AKAMPENE ISLAND

38SEASIDE SANATORIUM

39LENNOX CASTLE HOSPITAL

40ALCATRAZ PRISON

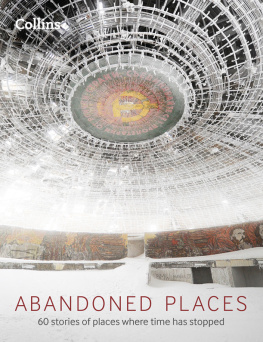

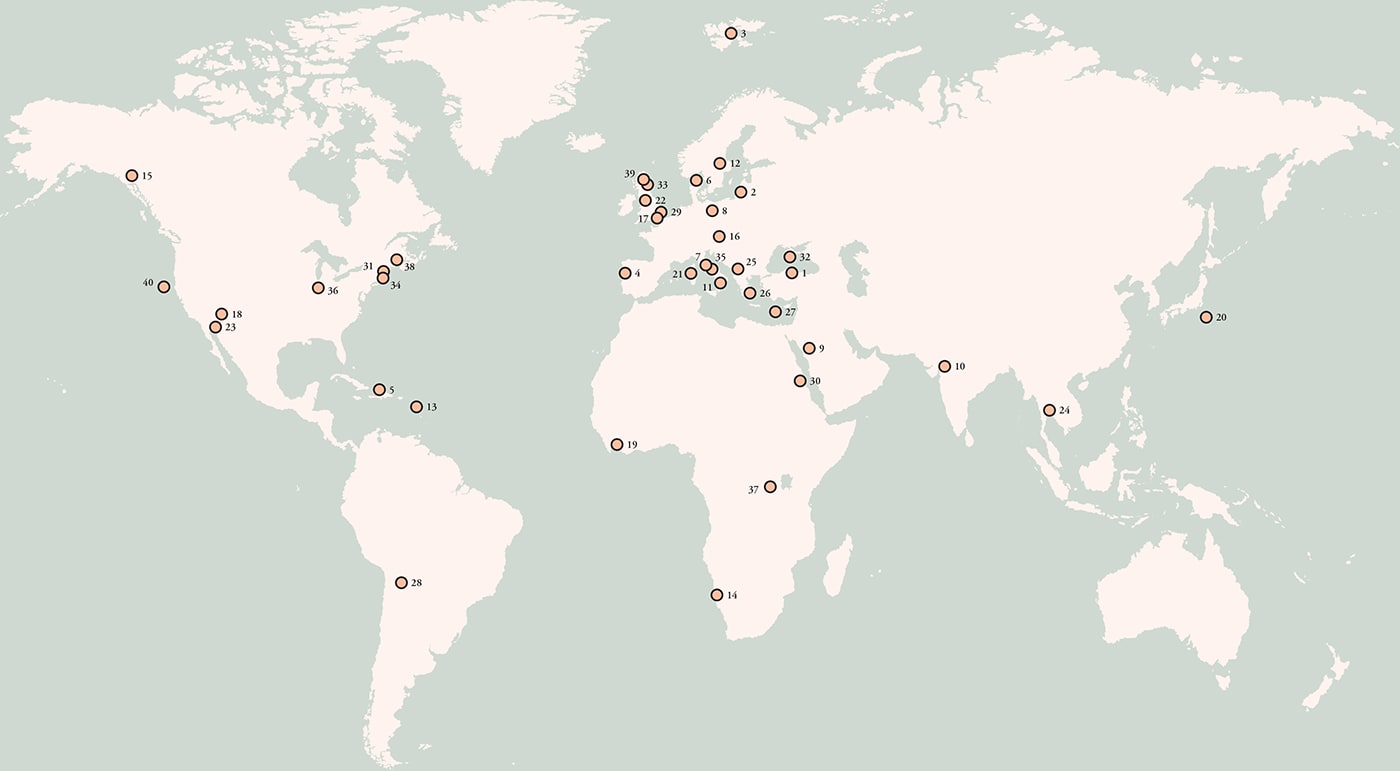

INTRODUCTION

To forget is to lose the power of recall. This un-getting, literally and etymologically, is a failure to remember things past, be they events, places or people. It can, of course, take the form of inadvertent neglect since forgetting is an essential, vital even, human fallibility. We talk about something slipping our minds, for instance, when missing appointments or returning home empty-handed when specifically asked to buy bread or milk. Similarly, misplaced is a word used to convey a more temporary absence than lost. It holds within it, the idea of imminent, or at least potential, rediscovery. Likewise in the adage attributed to Paul Valry that a poem is never finished, merely abandoned abandonment surely holds the possibility of some kind of retrieval or reclamation. To be finished is to be dead and done with no coming back. Abandonment, meanwhile, can more readily be undone with a little attention. The discarded, picked up again and the deserted, re-populated, say. Or so we perhaps like to think. The emptying of towns and city centres during the Covid-19 pandemic provided us with a graphic illustration, should it be needed, of how quickly hubs of life can go deathly quiet. How whole modes of contemporary being and urban economic activity might become suddenly obsolete overnight. History and indeed this book is full of places eventually rendered surplus to requirement by the most subtle shifts in patronage, trade, politics, health care, social custom and climate. Not all of them are worth mourning. Some we might wish never to remember or care to visit and others are too awful to forget. But the mapping of the relinquished (and in a few instances the repurposed) in the light of such recent events has never seemed more urgent or relevant. Their stories (hopefully) can teach us important lessons about impermanence, consumption, booms and busts, industrialization and the environment, the hubris of mankind and the unreliability of memory and memorialization. A future direction of travel is, after all, what we customarily study maps for.

The seeds of this gazetteer of the forsaken, sidelined, uninhabited and uninhabitable, though, might be said to have been sown by both the epidemic and the story of Poveglia, related in an earlier book, Atlas of Improbable Places. Poveglia is a small island 8km (5 miles) off Venice whose chief inhabitants these days are its ghosts, metaphorically speaking (though there are plenty who claim it is one of the most haunted locations on earth). It has, arguably, every right to that title given the grimmer uses that its 18 acres (7 hectares) have been put to over the years. Following the advent of the Black Death in the 1340s and again with the spread of the Bubonic Plague in the 1600s, it was here that the diseased and the dying from the island Republic itself were unceremoniously dumped and buried, often while still alive, in mass graves. For centuries, those wishing to enter Venice were required to stay on Poveglia for forty days before they were allowed in. This period, equal to the spell Jesus spent fasting and being tempted by the Devil in the Judean desert, was referred to numerically in the Italian as quarantine. The word duly became universally applied to the practice of isolating those suspected of carrying infectious diseases. A practice that until 2020, most of us living in affluent countries probably considered more generally reserved for travelling animals or consigned to the era before mass immunizations and antibiotics.

The test of time is more usually endurance. But in testing times whats lost can loom larger still. The ability to travel freely was among the casualties of this epidemic. Yet a scan of certain cityscapes brings us face to face with desolate buildings that could admonish our forgetfulness about how the ability to journey without falling sick was hard won and of the brutality of treatments meted out to those once deemed ill or undesirable.

Here then is a compendium of the misplaced and the neglected. Ruins, ancient and modern, beautiful, ugly and appalling, and in varying states of appreciation and restoration, or lack of thereof. The ungotten and the forgotten no one remembers. Abandonment is not a cause to give up all hope but the opposite, if anything, encouraging us all to think longer and harder about the world to come and what might be worth salvaging from the wreckage.

VACANT PROPERTIES

BYKADA ORPHANAGE

ISTANBUL, TURKEY

40 51' 39" N / 29 07' 24" E

The capital of both the Byzantine and Ottoman Empires, the old city of Istanbul (known as Constantinople until 1930), stands on seven hills on a triangular peninsula poised between Asia and Europe. For thousands of years it served as both a bridge and a barrier to traffic to the east and west. Washed by the waters of the three seas, the Golden Horn, the Bosphorus and the Sea of Marmara, its ancient walls with their turrets and crenellations endure to this day. As do its most imposing buildings, the Aya Sofya, commissioned by the Byzantine emperor Justinian and consecrated as a Christian church in AD 537 and the Ottoman Blue Mosque (Sultan Ahmet Camii) with its minarets and exquisite tiled interiors, completed in 1616 both monuments to the citys place at the crossroads of history. And its place as a seat of imperial and spiritual power, one of religious congruence and conflict, mercantile and maritime trade, piety and avarice, high art and low cunning, violence and intrigue. However, such edifices in brick, marble, tile and stone, tell only half the story of Turkeys rich architectural heritage. Before the 20th century, a great majority of buildings erected in and around Istanbul were of wooden construction. At Polatl in Turkeys interior, near the modern-day capital Ankara, are the still extant remains of the juniper-and-pine tomb and 40-metre-high funeral mound of King Midas, the legendary ruler of the Iron Age kingdom of Phrygia. Believed to be the oldest intact wooden structure in the world, that the tomb has survived is, of course, nothing short of a miracle, when many other fabled planked temples, palaces, houses and bridges the world over have, predictably, succumbed to fire, rot and woodworm, or merely been torn down and replaced with supposedly sturdier masonry materials.