ATLAS of the UNEXPECTED

Haphazard discoveries, chance places and unimaginable destinations

TRAVIS ELBOROUGH

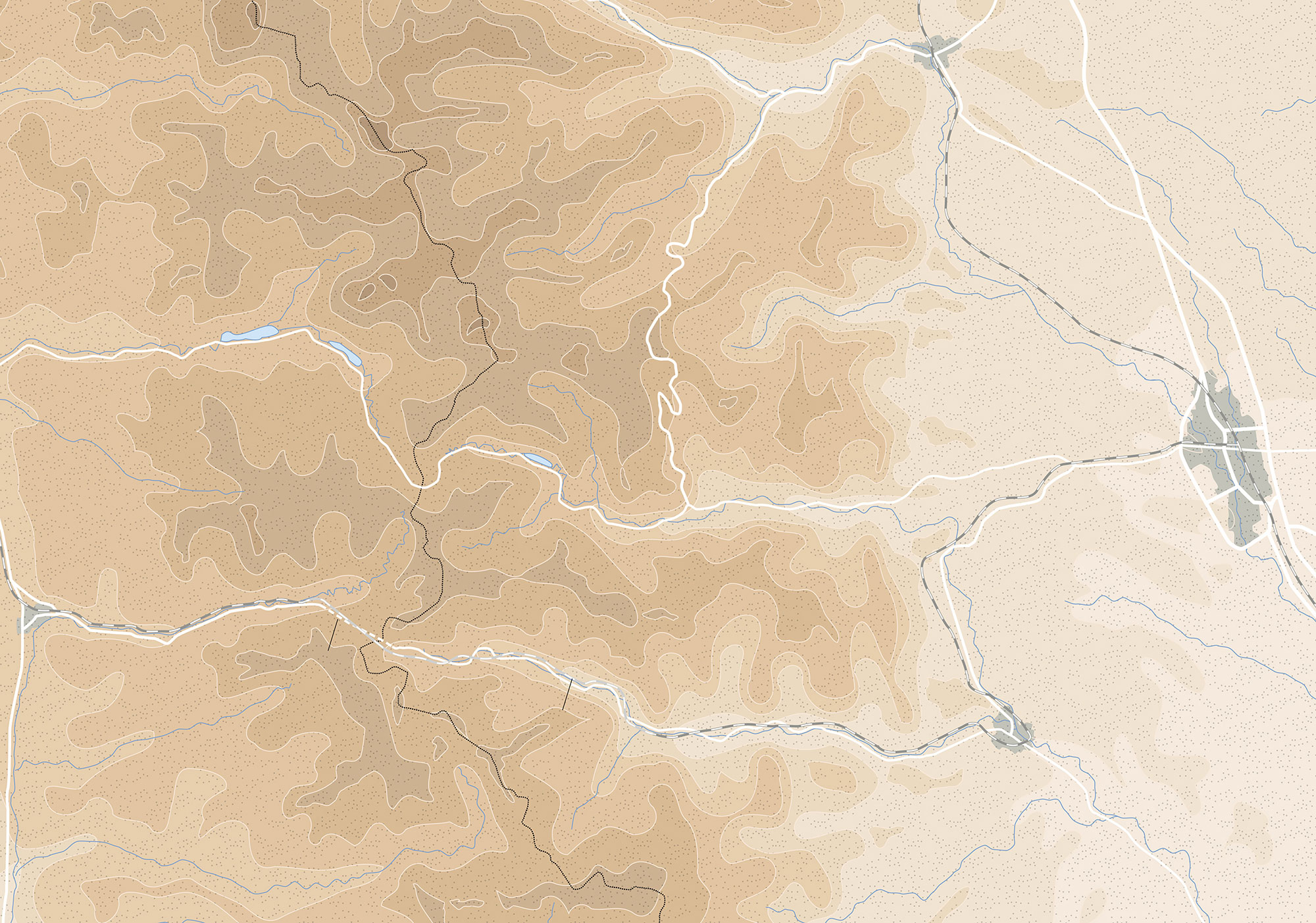

MAPS BY MARTIN BROWN

1 MADEIRA ARCHIPELAGO | 2 DERINKUYU UNDERGROUND CITY |

3 VASELINE | 4 THE DEAD SEA SCROLLS |

5 CAHOKIA MOUNDS | 6 POMPEII |

7 FLY GEYSER | 8 GALPAGOS ISLANDS |

9 GEORGIA COLONY | 10 CHEMAINUS |

11 BUZLUDZHA MONUMENT | 12 FREETOWN |

13 FRESHKILLS PARK | 14 FORT HOUSE |

15 CHESS CITY | 16 FORDLNDIA |

17 GIBSONTON | 18 NOWA HUTA |

19 NEFT DASHLARI | 20 MANSHIYAT NASER |

21 CALETA TORTEL | 22 JAISALMER FORT |

23 JUST ROOM ENOUGH ISLAND | 24 SPIEGELHALTERS JEWELLERS |

25 MONEMVASIA | 26 UROS FLOATING ISLANDS |

27 CLIFF OF BANDIAGARA | 28 KOROWAI TREEHOUSES |

29 LASCAUX CAVES | 30 XUANKONG SI |

31 MATMATA VILLAGE | 32 SHELL GROTTO |

33 COOBER PEDY | 34 MOVILE CAVE |

35 THE PETRIFYING WELL | 36 AOGASHIMA |

37 ZHANGYE DANXIA LANDFORM | 38 SLOPE POINT |

39 GLASS BEACH | 40 LAKE HILLIER |

41 GRNER SEE | 42 CAT ISLAND |

43 GRAND TSINGY | 44 HITACHI SEASIDE PARK |

45 CANFRANC STATION |

INTRODUCTION

I n Greek mythology, Atlas is a Titan whose punishment for leading a revolt against the Olympian gods is to bear the weight of the heavens upon his shoulders. It was Gerardus Mercator, the foremost geographer of the Renaissance, who first applied the name to a collection of maps and charts. Born Gerhard Kremer, the son of a cobbler, Gerardus Mercator was the esteemed court cosmographer to Duke Wilhelm of Cleve in Duisberg, Germany. Published in the spring of 1595, and four months after the mapmakers own death at the age of eighty-two, his Atlas, sive Cosmographicae meditationes de fabrica mundi carried an illustration of the great Titan with the whole world in his hands on its frontispiece, accompanied by the statement, I have set this man Atlas so notable for his erudition, humaneness, and wisdom as the model for my imitation.

Completed by Mercators son, Rumold, and containing 107 maps of which 102 described regions in Europe, but lacking charts of Spain and Portugal Mercators Atlas fell somewhat short of the full fabrickd world of its title. Its instigator had certainly intended to include detailed maps of all the other continents, but a series of strokes that left him partially paralysed and near blind had prevented him from achieving that ambition. Of the maps he did supply, those of The Arctic Lands were largely works of fiction, with four islands around the North Pole and a landmass called Frisland, subsequently found not to exist the latter, supposedly having been copied from an earlier fraudulent map by Nicol Zeno, the fifteenth century Italian explorer suspected of faking most of his voyages. Mercator not only gave us the concept and name of the atlas, but his specific method of mapping opened up the world to all future globetrotting, by solving the problem of representing the spherical Earth on a flat piece of paper. So-called Mercators projection works by rendering parallels and meridians as straight lines that are mathematically spaced from the equator in such a way as to produce an accurate ratio of latitude to longitude that enabled mariners, in particular, to plot a course from one place to another with precision. This rigorously systematic cartography puts reality at the mercy of representation, stretching the northern and southern regions of the globe in order to keep the bearings orderly. One downside is that it warps the world in the Northern Hemispheres favour, most famously resulting in a Greenland far vaster than either South America or Australia on world maps pinned to classroom walls across the globe. Its virtues clarity and sheer navigational practicality among them have seen its principles applied in everything from the composition of the first meteorological chart by Edmond Halley in 1686 to the first satellite map of the United States in 1974. Google, along with countless other internet map providers, continues to cleave to Mercator, despite the arrival of alternative mapping schemes developed since pin-point-accurate satellite geolocation became available.

Perhaps deep down this is an admission of sorts that, even in an era when few activities online or out in the real world go untracked, the map can never truly be the territory, as the old adage has it.

We look to maps to lead us where we need to go, just as our ancestors did, but the journey can sometimes be as interesting as the destination, and the chart as delightful as the ground covered. After all, Mercator never set sail on any ocean himself, neither did he appear to have travelled much beyond the Low Countries, but by giving us the world on paper, he created a form in the atlas for imaginative suggestion and dreaming as much as scientific exploration.

The world has become both larger and smaller since Mercators day, when swathes of it remained subject to rumour, myth and speculation. Our internet-aided present puts the once entirely unknown at our fingertips, distorting distances in time and space beyond anything previously imagined in cartography. Surprises, we are led to believe, are thinner on the ground now, because almost everything can be seen on a screen. Yet the unexpected, a term that dates back to the 1580s and the period when Mercator was perfecting his projection maps, has not been banished entirely. Our appetite for the unusual, the out of the ordinary has, if anything, only been heightened by new technology. The scanning and sharing of fresh information and imagery provides a spur to seeking out fresh destinations and experiences, just as the original Atlas did in its day.

Atlas of the Unexpected, then, is a compendium of places odd and enchanting, ancient and modern touched by the certainty of chance and the often haphazard nature of what passed for discovery in the golden age of exploration. Expect the unexpected to come from some element of a sites geography, architecture, or present or past state of being. Unimaginable in some instances, and all but uninhabitable in others, these are places with stories to tell that help remind us of the enduring strangeness of our planet.

ACCIDENTAL DISCOVERIES