Contents

Guide

ALTERED STATES

GREEN GABLES AND GOLD NUGGETS

THE OLD NEW WORLD

CITIES OF GOLD AND BANANA REPUBLICS

THE OLD COUNTRIES

SCIENCE AND SORCERY, SHTETLS AND SOVIETS

HERE BE DRAGONS (AND TROLLS)

FAKE BRITAIN AND SHAM ROCK

BEYOND THE SILK ROAD

FROM PESHAWAR TO THE PENINSULA

THINGS COME TOGETHER

WILDS, WAVES, WORLDS AND WARS

THE LAND OF THE RISING GUNDAM

JOURNEY TO THE EAST

THE ORIGINAL LAND OF OZ

THE NIGHTMARE CONTINENT

ISLAND HOPPING

LOST WORLDS OF THE WESTERN SEA

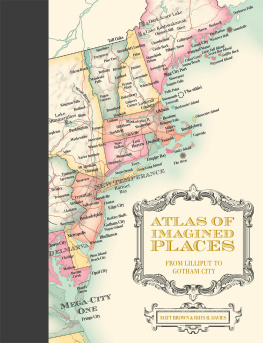

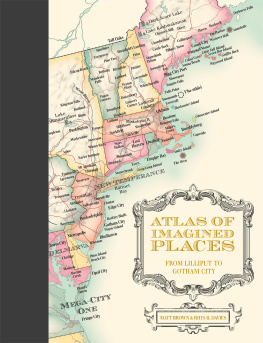

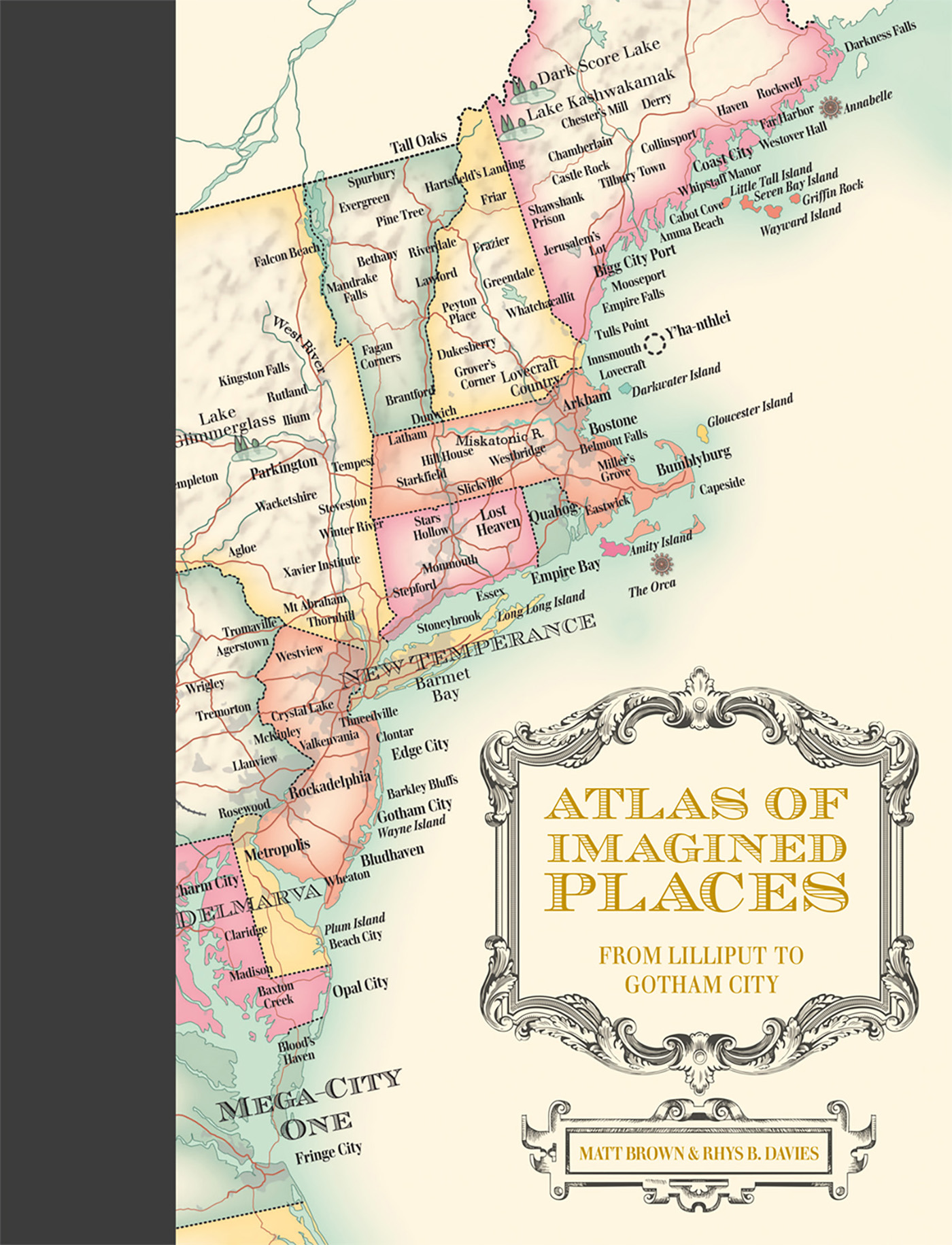

elcome to the atlas of places that do not exist. Across these pages, youll find around 5,000 fictional locations, including towns, cities, countries, seas, buildings, deserts, mountains, forests, underwater tunnels, space elevators and at least one giant, time-manipulating baby buried in an Antarctic glacier. None are found in a conventional atlas, but all exist in works of the imagination.

elcome to the atlas of places that do not exist. Across these pages, youll find around 5,000 fictional locations, including towns, cities, countries, seas, buildings, deserts, mountains, forests, underwater tunnels, space elevators and at least one giant, time-manipulating baby buried in an Antarctic glacier. None are found in a conventional atlas, but all exist in works of the imagination.

This atlas began life in 2018, when we published our map Fake Britain on the website Londonist.com, followed by its companion Unreal London. We got so much positive feedback that the Fake Britain project escalated into a full-blown world atlas of fictional locations, which you now hold in your hands.

The maps feature age-old legends like El Dorado, Atlantis, Utopia, Camelot, the Mountains of Kong and lost continent of Lemuria. Weve woven in inventions from classic literature, such as Charles Dickens Coketown, Mary Anne Evans Middlemarch, Prousts Combray or Garca Mrquezs Macondo. Hundreds of locales from popular culture are baked into the mix, including Gotham City, Metropolis, Hogwarts, Twin Peaks, Erinsborough, Vice City, Schitts Creek, Arendelle, King Solomons Mines, a heap of Pokmon gym-cities, and hardest to map of all Springfield from The Simpsons. Weve also peppered the maps with fictional locations from more surprising sources, including military training scenarios, theme-park rides, a Frank Zappa song, TV commercials and even a few unfortunate slips of the tongue that led to the birth of entire fictional nations (see Central America and Africa maps ).

Dozens of genres and subgenres emerge from the pages. Look out for the many Ruritanian romances of central Europe, the international Utopias inspired by Thomas Mores original and their dystopian cousins, Brazilian telenovelas, Australian soaps, Robinsonades, high-school manga, Scandi noirs, polar weirdness, the lost world tales of Africa and South America, and many more.

We hope that the atlas helps you to better understand the geography of your favourite works of fiction. But it also serves as a springboard for finding stories you might not already know. Look at the area around your hometown; do you recognize all the nearby creations? Or perhaps check out our entry for a country youre planning on visiting, and track down the local fiction. Then theres the joy of looking for unusual juxtapositions. The village of Asterix the Gaul is right next door to the climactic battleground of Saving Private Ryan; while the stranded hero of Cast Away might have been within rescue range of Captain Nemos Nautilus (and those are just the Tom Hanks connections).

Its a whole new world!

WHAT DO WE MEAN BY A FICTIONAL PLACE?

It might seem like a question with an easy answer. A fictional place is any location that has no existence in reality, a creation of pure imagination. Yet, in compiling this atlas, weve found that not all fictional places are created equal. Weve identified four different classes listed in order below, from the most heavily fantastical, down to those grounded closest to reality:

An entirely made-up place, but which exists somewhere other than our familiar Earth (e.g. Narnia, Westeros). Such places are not shown in this atlas.

An entirely made-up place, set somewhere on Earth (e.g. Liberty City, Genovia, the Island of Sodor). These places make up the majority of locations in the atlas.

A location whose name is fictional, but which is heavily based on somewhere real (e.g. Thomas Hardys Wessex towns, or Charlotte Bronts Villette, heavily modelled on Brussels). These too are shown in the atlas.

A location whose name is real, but whose characteristics have been fictionalized (e.g. the Oxford of His Dark Materials). We have not mapped such locations.

Thus, to qualify for inclusion a place has to have at least a fictional name and to exist upon our Earth.

For visual media, weve generally mapped locations to where theyre meant to be, rather than where they were filmed. It frequently has to be that way. For example, had we matched Sokovia (from Marvels Avengers: Age of Ultron)to its filming location, then this Central European country would lie within the north London suburb of Hendon, the Battle of Sokovia being filmed here at the Metropolitan Polices former training college. Elsewhere, however, we have used filming locations as secondary canon in the absence of other clues.

DECISIONS, DECISIONS ...

Read the introduction to almost any cartographic book and youll spot a health warning: Maps are not 100 per cent faithful reproductions of the terrain they seek to cover, but reflect the biases of their compilers (or something to that effect). This observation has become something of a clich, though it is grounded in truth. All mapmakers are faced with choices about what to include and what to exclude. The decisions they reach may be influenced by political or cultural biases, or to suit the needs of a particular audience. A factual atlas of the world published in China will look very different to one published in India, the UK or Mozambique. The print language will vary, of course, but so too might accepted political boundaries and the locations given most prominence.

A fictional atlas, as we have discovered, is even more prone to partisanship. For starters, it cannot hope to be comprehensive. While nobody knows just how many novels have ever been published in human history, they must run into the tens of millions; as of December 2020, IMDb.com the worlds largest database of film, television and video games listed 7.5 million titles, up from 6.5 million at the start of the year. And then there are radio plays, podcasts, folklore, comics, board games and other media to consider. The fruits of human creativity are essentially infinite, and while not all of these works will include fictional locations, a fraction of infinity is itself still infinite.

elcome to the atlas of places that do not exist. Across these pages, youll find around 5,000 fictional locations, including towns, cities, countries, seas, buildings, deserts, mountains, forests, underwater tunnels, space elevators and at least one giant, time-manipulating baby buried in an Antarctic glacier. None are found in a conventional atlas, but all exist in works of the imagination.

elcome to the atlas of places that do not exist. Across these pages, youll find around 5,000 fictional locations, including towns, cities, countries, seas, buildings, deserts, mountains, forests, underwater tunnels, space elevators and at least one giant, time-manipulating baby buried in an Antarctic glacier. None are found in a conventional atlas, but all exist in works of the imagination.