ATLAS OF UNTAMED PLACES

AN EXTRAORDINARY JOURNEY THROUGH OUR WILD WORLD

CHRIS FITCH

1 SKELETON COAST

2 FURNACE CREEK

3 LAKE NYOS

4 DOME ARGUS

5 CAVE OF CRYSTALS

6 EISRIESENWELT

7 YELLOWSTONE

8 SUNDARBANS

9 GANGKHAR PUENSUM

10 HANG SON DOONG

11 DARIN GAP

12 THE SUDD

13 CHALLENGER DEEP

14 NORTH SENTINEL ISLAND

15 KRUBERA

16 MALIAU BASIN

17 GREEN LINE

18 CHERNOBYL EXCLUSION ZONE

19 THE DEMILITARISED ZONE

20 THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN ARSENAL REFUGE

21 ODESSA CATACOMBS

22 PLEISTOCENE PARK

23 CENTRALIA

24 LAC DE GAFSA

25 MODO ISLAND

26 JABUKA

27 LAKE MARACAIBO

28 QIANTANG RIVER

29 LOUGHAREEMA

30 EMPTY QUARTER

31 THE MOUNT MABU RAINFOREST

32 TREE OF TNR

33 ININI

34 KAFFEKLUBBEN ISLAND

35 INACCESSIBLE ISLAND

36 DIOMEDE ISLANDS

37 HERSCHEL ISLAND

38 SOCOTRA

39 CAPE FLORAL REGION

40 BIAOWIEZA FOREST

41 MERU NATIONAL PARK

42 ENDEAVOUR RIVER

43 TE UREWERA

44 OKAVANGO

45 YASUN NATIONAL PARK

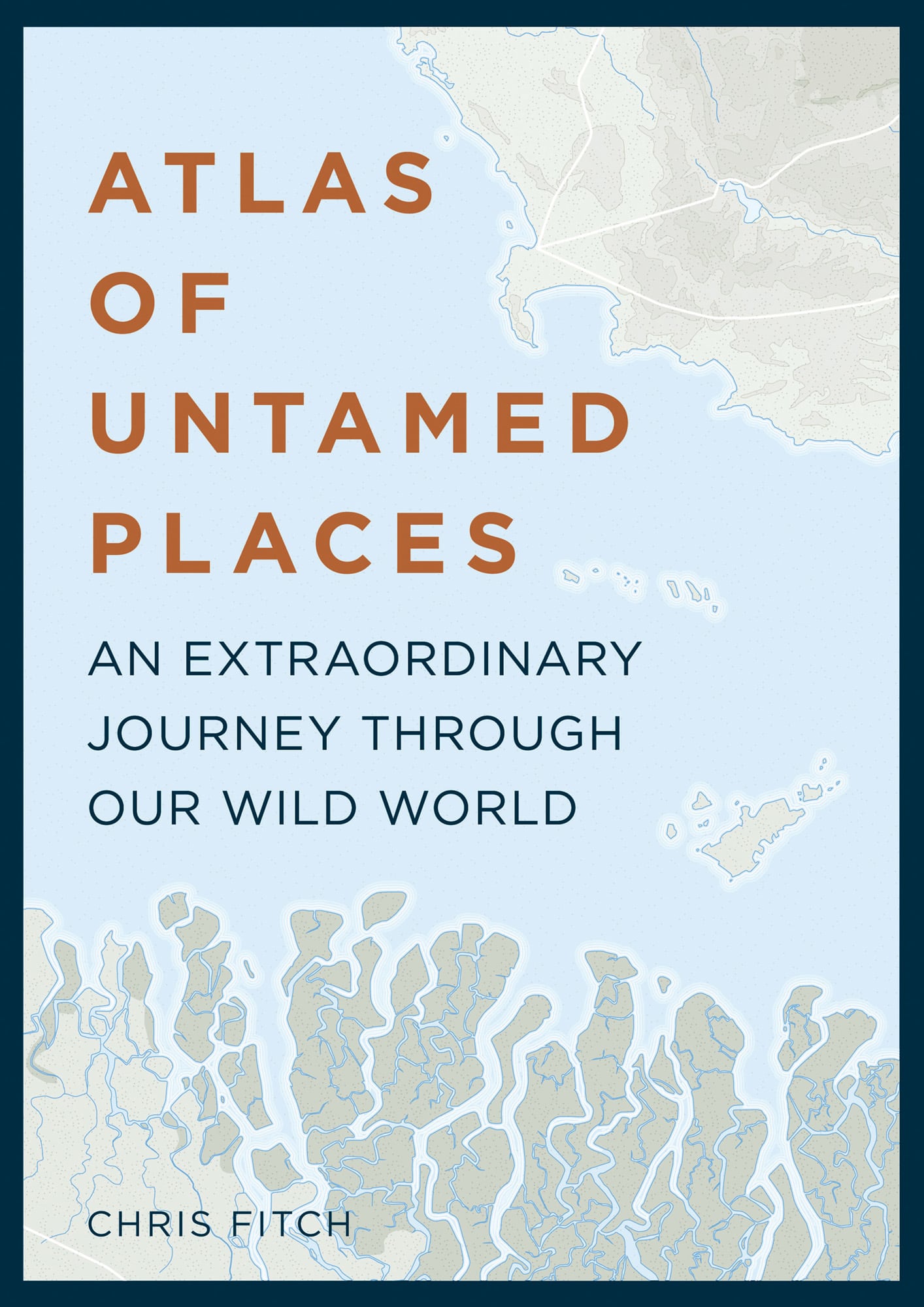

INTRODUCTION

Wilderness is a necessity, insisted the naturalist John Muir. Similarly, writer Henry David Thoreau passionately argued that we need the tonic of wildness. While these may be two of the most well-known examples, there has been no shortage of strong words from influential individuals over the years urging us to recognise the necessity of our relationship with the wilderness of the natural world. Equally, there has been just as much written about the contemporary threats facing that same wilderness. While the romantic notion of a paradise subdued by human action may feel like a recent phenomenon, iconic poet William Wordsworth and his contemporaries were angrily arguing back in the early nineteenth century about the apathetic way we were conquering and taming the wilderness that so captivated him.

Two centuries later, its harder than ever to disagree with Wordsworths assessment: Little we see in Nature that is ours. Whichever way you look at it, the world has overwhelmingly been developed and controlled. Trees felled, oceans emptied, wild animals eradicated. Leashed and domesticated, the true wildness thoroughly bred out. Previously blank spaces on the map filled in with roads, fields and urban sprawl. The modern era is even on the verge of being officially declared an entirely new geological age: the Anthropocene the era of man. Its a declaration that confirms humanity as the most dominant force on the planet.

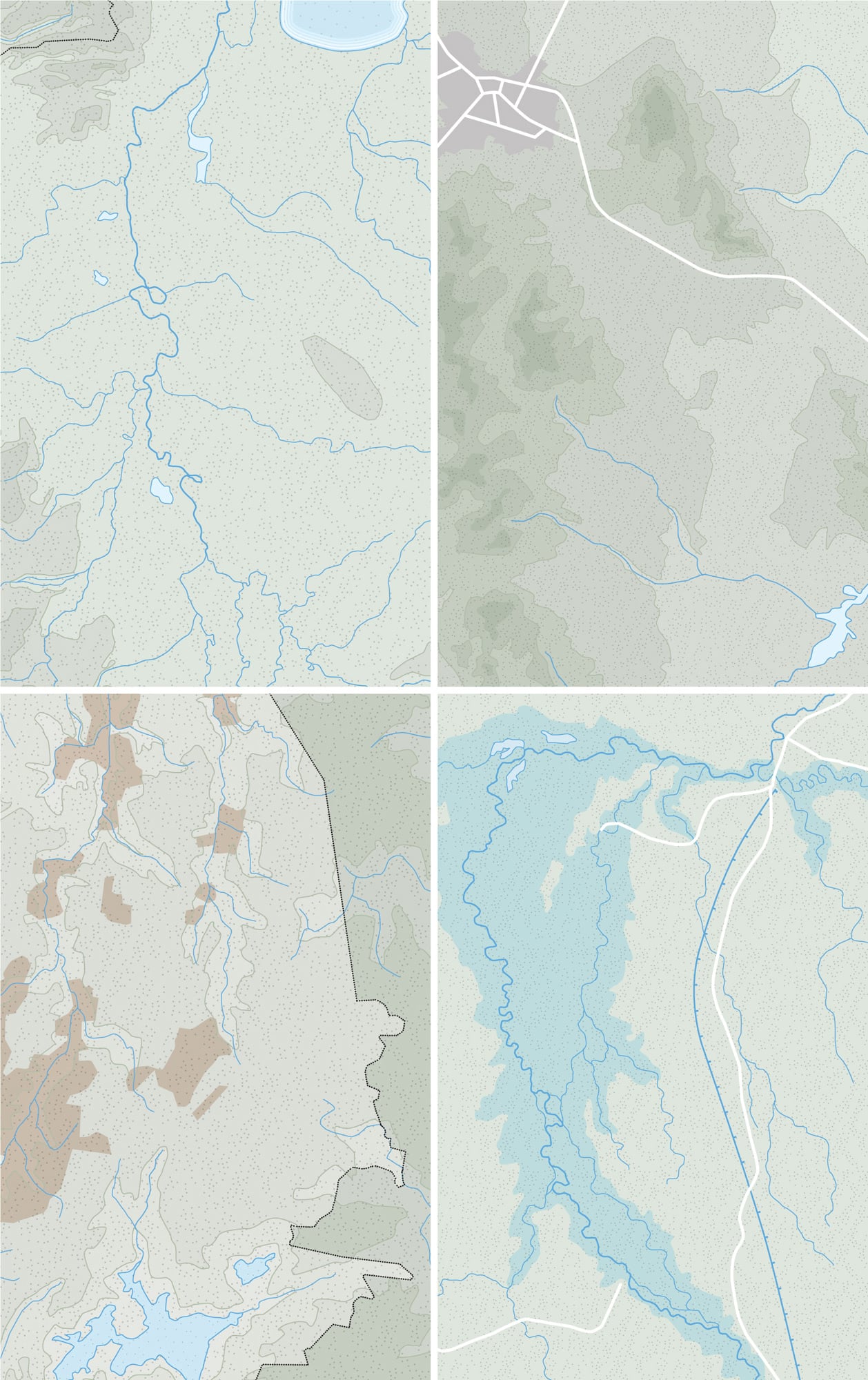

Yet, despite this, arent we still enamoured by those unpredictable and undeveloped landscapes? Remote and exotic, full of mysteries and unanswered questions visions of far-flung wilderness tug at our sense of wanderlust. While the so-called Age of Discovery, the days of sailing over the horizon in search of new worlds, may largely be behind us (in itself, perhaps no bad thing) it doesnt mean there arent still many uniquely wild places that we could describe, for one reason or another, as untamed. As progress tames the world, spreading the homogeneous monotony that almost all of us inhabit, these places refuse to comply, firmly resisting the creeping tentacles of development. This book is by no means an exhaustive list of the planets wildest or most untamed places. Instead, it celebrates forty-five wild and fascinating stories including isolated realms such as remote islands; unclimbed peaks and other untouched lands; natural wildernesses such as lush forests; extreme environments with intense heat or man-eating tigers; and even towns and other human creations since abandoned, overgrown and reclaimed by the natural world accompanied by an array of gorgeously detailed maps, which will hopefully inform and inspire.

EXTREME ENVIRONMENTS

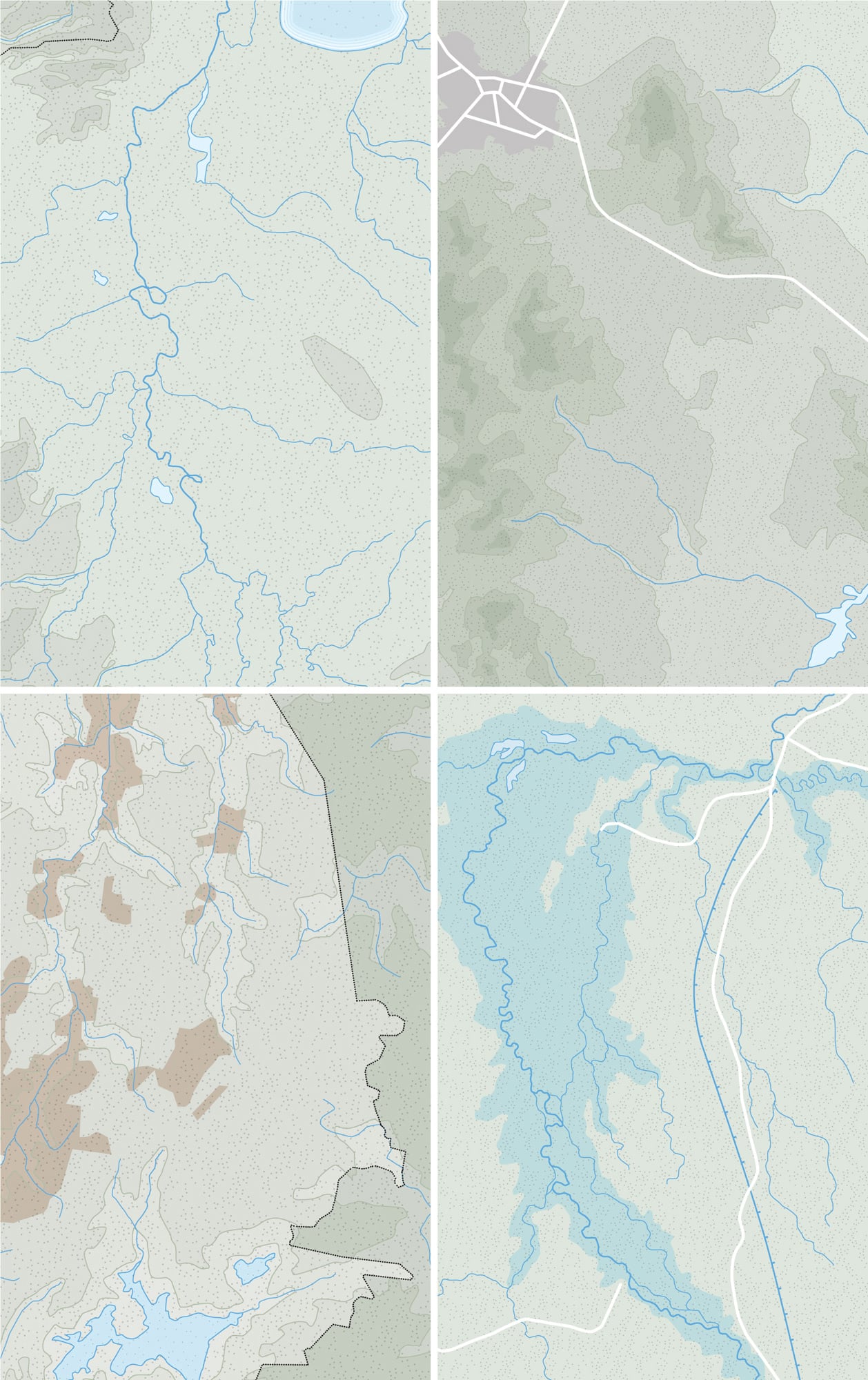

SKELETON COAST

NAMIBIA

Namib Desert

23 59' 46"S

14 27' 0"E

Death would be preferable to banishment to such a country.

S wedish explorer Charles John Andersson did not mince his words when discussing the possibility of being stranded on Namibias Skeleton Coast. Many generations of sailors, however, did not have the luxury of choosing between these two options, as instead this inhospitable coastline cruelly inflicted upon them first the latter, and then the former.

The name Skeleton Coast, for the northern portion of Namibias South Atlantic coastline, wasnt popularised until 1944, when John Henry Marshs book of that name told the amazing story of the ill-fated Dunedin Star, a liner whose entire crew had been miraculously rescued after being shipwrecked on the coast two years earlier. Its a rare happy ending for a narrative that has been told time and time again for five centuries, ever since brave and/or foolhardy sailors first attempted the long and treacherous maritime trade route between Europe and Asia which took them around the southern tip of Africa, past what is now South Africas famous Cape of Good Hope.

Marshs choice of title was nevertheless apt. First known as a place where the vertebrae and other skeletal remains of many beached whales could be found, in later years the term instead began to refer to the human victims who had failed to find a way out of this wild and unforgiving landscape. The physical conditions off the coast of Namibia make shipwrecks far from an unlikely outcome, as intensely thick sea fog, strong Atlantic gales, and the powerful Benguela Current combine to make it incredibly easy for ships to be driven into shallow waters and onto the shore completely against their will. Aside from the Dunedin Star, possibly the most famous of the coasts victims is the Eduard Bohlen, a steamer that was grounded in 1909. Thanks to the constant movement of dunes, the coastline itself is in perpetual flux hence, more than a century since the accident, the rusted hull of what was once the Eduard Bohlen now finds itself stranded several hundred yards inland, a striking monument to the Skeleton Coasts vicious nature emerging dramatically from the featureless sandscape.

Being shipwrecked anywhere in the world would undoubtedly be a fairly dangerous and unpleasant experience, but the Skeleton Coast is a different proposition entirely. Assuming sailors survived the rough conditions which led to their beaching in the first place, they would look up and down the coast to find themselves ominously surrounded by some of the hundreds of ships that had suffered the exact same fate. With extreme weather conditions ranging from scorchingly hot during the day and below freezing at night, plus rainfall so desperately low that fresh water is almost impossibly scarce, their chances of survival would be spirit-crushingly slim. Many shipwrecked sailors would lose their minds and begin drinking seawater, a one-way ticket to dehydration and death. Those who attempted to leave the coast and instead seek salvation inland would have quickly made the discovery that there were hundreds of miles of epic sand dunes and lifeless rocky outcrops of the Namib desert between them and civilisation. Many sailors walked incredibly vast distances across the barren landscape before eventually being overcome by the extreme conditions.