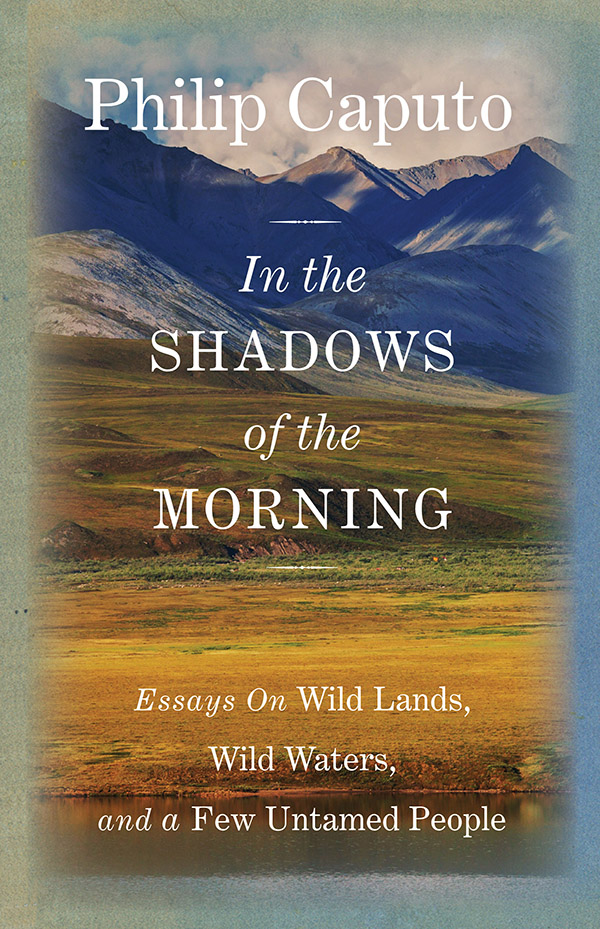

In the

SHADOWS

of the

MORNING

Books by Philip Caputo

A Rumor of War

Horn of Africa

DelCorsos Gallery

Indian Country

Means of Escape

Equation for Evil

Exiles

The Voyage

Ghosts of Tsavo

In the Shadows of the Morning

Thirteen Seconds: A Look Back at the Kent State Shootings

Ten Thousand Days of Thunder

Acts of Faith

Crossers

The Longest Road

In the

SHADOWS

of the

MORNING

Essays on Wild Lands, Wild Waters, and a Few Untamed People

Philip Caputo

LYONS PRESS

Guilford, Connecticut

An imprint of Globe Pequot Press

Copyright 2003, 2014 by Morris Book Publishing, LLC

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, PO Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

Lyons Press is an imprint of Globe Pequot Press.

Project editor: Staci Zacharski

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

eISBN 978-1-4930-1227-5

CONTENTS

PREFACE

I was born under a wandering star. I dont know how this came about. The first of my ancestors to immigrate to America arrived in 1885. A paternal great-grandfather laid track for the Great Northern Railway from Chicago to Seattle and for a while worked in the copper mines of Montana, after which he returned to Chicago and stayed put until his death in 1929. My mothers people also settled there in 1908 and never moved. So far as I know, they never had a desire to; nor did most of their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. It was as if the perilous journeys undertaken by the immigrant generation had exhausted the familys reserves of wanderlust, which it probably had never possessed in abundance. Before the New World beckoned, the people Im descended from had inhabited one small corner of southern Italy for centuries, so I have no idea where my own nomadic blood comes from.

Its stirred in me for as long as I can remember. My first eighteen summers were spent in the Wisconsin north woods, where my machinist father serviced canning factories and where I acquired a love of the outdoors, an itch to see what lay over the next hill or around the next bend in a river, and learned how to fish and shoot, along with such obsolete skills as tracking game, building a campfire in a wet woods, and navigating by the sun and the lay of the land. Some time later, as a newly minted college dropout, I hitchhiked, rode buses, and hopped freights through the West and down into Mexicomy Jack Kerouac phase. Still later, the US Marine Corps took me to Hawaii, Japan, Singapore, and finally Vietnam. That was followed by a long career as a foreign correspondent in the Middle East, Europe, and the Soviet Union. Since the age of twenty-one, Ive had fourteen different addresses and have lived in, worked in, and fought and covered wars in fifty-one countries on four continents, not to mention voyages in the South China Sea, the Caribbean, and the Atlantic.

Ive written about these journeys for several publications. The stories that follow have appeared, in somewhat different form, in Esquire , Islands , Mens Journal , the Miami Herald , National Geographic Adventure , National Geographic , the New York Times , and Sports Afield.

Taken together, they form a record of adventure travel spanning some twenty five years. Adventure travel is a term Im not entirely fond of, but I suppose we need it to distinguish modern modes of travel from those that entail some risk and hardship. By that definition, the act of getting from Point A to Point B on land or sea was an adventure for all travelers before the inventions of the steamship, the automobile, and the passenger plane, before there was a multibillion-dollar tourist industry to make even remote corners of the world accessible and comfortable, before the United States was spanned by interstate highways with convenient rest stops, motorist call-boxes, and franchise eateries offering high-fat Happy Meals.

Most of these stories are accounts of outdoor expeditions to wild places and on the open sea; some turn on hunting and fishingpursuits Ive followed since boyhood, without apologies. Readers will note a strong bias toward conservation and an equal disgust with the effects that sprawl and overdevelopment have had on our landscapesand on our collective soul. Im not a pantheistic nature worshiper; nevertheless, my response to the natural world is essentially religious: I see the hand of God in mountains, forests, and wild rivers and think our society would be less troubled if there were more of those and less of shopping malls, sterile subdivisions, and all the detritus of a consumer-driven culture.

Ive included three storiesfrom Afghanistan, Sudan, and Vietnamthat are about war or its effects. Those are not strictly tales of adventure, because war, as Erich Maria Remarque told us a long time ago, never is an adventure to those who must fight in it.

Philip Caputo

May 2002

THE ENFIELD AND THE KORAN

1980

On the Pakistani side of the Khyber Pass, along the road that climbs and twists to Torkam on the Afghan frontier, painted stone tablets add splashes of color to the brown Khyber hills. They stand singly in some places; elsewhere they cluster like tombstones in a crowded graveyard, odd-looking symbols chiseled on their facades: crossed sabers and crossed rifles, wreaths, crowns, and banners bearing names like Dorsetshire and Gordon Highlanders. The tablets are not tombstones but markers commemorating the exploits of the British regiments that played in the rougher innings of what a nineteenth-century English officer called the Great Game.

There is another kind of memorial on the Afghan side of the border, at a place called Gondabak. It is a stark beige-colored hill, no different from all the other stark beige-colored hills except for the extraordinary number of human bones that have been found under its rocks by the people who look for such things. The bones are all that is left of the 44th Foot, which formed the rear guard of a British and Indian army retreating from Kabul in 1842, the last year of the First Afghan War. At Gondabak, the regiment made one of those last stands that later provided raw material for historical novelists and the Hollywood illusion factory. But it was the real thing for the 44th on that winters day nearly a century and a half ago: Afghan tribesmen overran the regiment, massacring forty-five hundred troops and twelve thousand camp followers and sparing only a handful. One of them was told to return to India and inform Her Majestys colonial government that the Khyber Pass could be very hazardous to an Englishmans health.