CONTENTS

About the Author

Mustered out of the Marine Corps in 1967, Philip Caputo went on to a prize-winning career as a journalist, covering the war in Beirut and the fall of Saigon before leaving the Chicago Tribune to devote himself to writing full-time. His novels are Horn of Africa, DelCorsos Gallery, Indian Country and Equation for Evil. He is also the author of a collection of novellas, Exiles, and a second volume of memoir, Means of Escape. A contributing editor for Esquire, Philip Caputo has also written for the New York Times, the Boston Globe and the Los Angeles Times. He and his wife, Leslie Blanchard Ware, live in Connecticut.

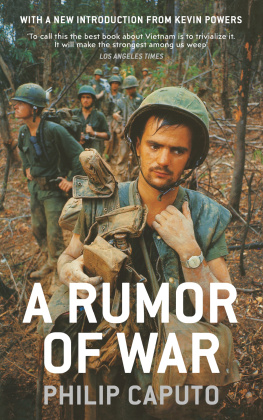

Philip Caputo

A RUMOR OF WAR

with an introduction by

Kevin Powers

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Version 1.0

Epub ISBN 9781473591851

www.penguin.co.uk

Copyright Philip Caputo 1977, 1996

Introduction copyright Kevin Powers 2017

Cover: US Marine patrol, Vietnam, October 1966 Larry Burrows/Time Magazine/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

Philip Caputo has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work

Grateful acknowledgement is made to Mr G.T. Sassoon and to The Viking Press for permission to reprint lines from The Effect, Dreamers and Base Details from Collected Poems by Siegfried Sassoon, copyright 1918 by E.P. Dutton Co., 1946 by Siegfried Sassoon; and for permission to reprint lines from Elegy and Aftermath from Collected Poems by Siegfried Sassoon, copyright 1920 by E.P. Dutton Co., 1948 by Siegfried Sassoon. Grateful acknowledgment is made to The Owen Estate and to Chatto & Windus Ltd for permission to reprint lines from Arms and the Boy and Apologia Pro Poemate Meo from Collected Poems by Wilfried Owen, edited by C. Day Lewis, copyright Chatto & Windus Ltd 1946, 1963

First published in the United States by Holt, Rinehart and Winston in 1977

First published in Great Britain by Macmillan in 1977

First published by Pimlico in 1999

This edition first published by The Bodley Head in 2017

VINTAGE

20 Vauxhall Bridge Road,

London SW1V 2SA

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

TO

SERGEANT HUGH JOHN SULLIVAN

C Company, First Battalion, Third Marines

KILLED IN ACTION, JUNE 1965

and

FIRST LIEUTENANT WALTER NEVILLE LEVY

C Company, First Battalion, First Marines

KILLED IN ACTION, SEPTEMBER 1965

AND YE SHALL HEAR OF WARS AND RUMORS OF WARS. SEE THAT YE BE NOT TROUBLED, FOR ALL THESE THINGS MUST COME TO PASS, BUT THE END IS NOT YET. FOR NATION SHALL RISE AGAINST NATION AND KINGDOM AGAINST KINGDOM THEN SHALL THEY DELIVER YOU UP TO BE AFFLICTED AND SHALL PUT YOU TO DEATH BUT HE THAT SHALL ENDURE UNTO THE END, HE SHALL BE SAVED.

Matthew 24:613

Prologue

In thy faint slumbers I by thee have watchd

And heard thee murmur tales of iron wars.

Shakespeare

Henry IV, Part 1

This book does not pretend to be history. It has nothing to do with politics, power, strategy, influence, national interests, or foreign policy; nor is it an indictment of the great men who led us into Indochina and whose mistakes were paid for with the blood of some quite ordinary men. In a general sense, it is simply a story about war, about the things men do in war and the things war does to them. More strictly, it is a soldiers account of our longest conflict, the only one we have ever lost, as well as the record of a long and sometimes painful personal experience.

On March 8, 1965, as a young infantry officer, I landed at Danang with a battalion of the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade, the first U.S. combat unit sent to Indochina. I returned in April 1975 as a newspaper correspondent and covered the Communist offensive that ended with the fall of Saigon. Having been among the first Americans to fight in Vietnam, I was also among the last to be evacuated, only a few hours before the North Vietnamese Army entered the capital.

Although most of this book deals with the experiences of the marines I served with in 1965 and 1966, I have included an epilogue briefly describing the American exodus. Only ten years separated the two events, yet the humiliation of our exit from Vietnam, compared to the high confidence with which we had entered, made it seem as if a century lay between them.

For Americans who did not come of age in the early sixties, it may be hard to grasp what those years were likethe pride and overpowering self-assurance that prevailed. Most of the thirty-five hundred men in our brigade, born during or immediately after World War II, were shaped by that era, the age of Kennedys Camelot. We went overseas full of illusions, for which the intoxicating atmosphere of those years was as much to blame as our youth.

War is always attractive to young men who know nothing about it, but we had also been seduced into uniform by Kennedys challenge to ask what you can do for your country and by the missionary idealism he had awakened in us. America seemed omnipotent then: the country could still claim it had never lost a war, and we believed we were ordained to play cop to the Communists robber and spread our own political faith around the world. Like the French soldiers of the late eighteenth century, we saw ourselves as the champions of a cause that was destined to triumph. So, when we marched into the rice paddies on that damp March afternoon, we carried, along with our packs and rifles, the implicit convictions that the Viet Cong would be quickly beaten and that we were doing something altogether noble and good. We kept the packs and rifles; the convictions, we lost.

The discovery that the men we had scorned as peasant guerrillas were, in fact, a lethal, determined enemy and the casualty lists that lengthened each week with nothing to show for the blood being spilled broke our early confidence. By autumn, what had begun as an adventurous expedition had turned into an exhausting, indecisive war of attrition in which we fought for no cause other than our own survival.

Writing about this kind of warfare is not a simple task. Repeatedly, I have found myself wishing that I had been the veteran of a conventional war, with dramatic campaigns and historic battles for subject matter instead of a monotonous succession of ambushes and fire-fights. But there were no Normandies or Gettysburgs for us, no epic clashes that decided the fates of armies or nations. The war was mostly a matter of enduring weeks of expectant waiting and, at random intervals, of conducting vicious manhunts through jungles and swamps where snipers harassed us constantly and booby traps cut us down one by one.

The tedium was occasionally relieved by a large-scale search-and-destroy operation, but the exhilaration of riding the lead helicopter into a landing zone was usually followed by more of the same hot walking, with the mud sucking at our boots and the sun thudding against our helmets while an invisible enemy shot at us from distant tree lines. The rare instances when the VC chose to fight a set-piece battle provided the only excitement; not ordinary excitement, but the manic ecstasy of contact. Weeks of bottled-up tensions would be released in a few minutes of orgiastic violence, men screaming and shouting obscenities above the explosions of grenades and the rapid, rippling bursts of automatic rifles.

Next page