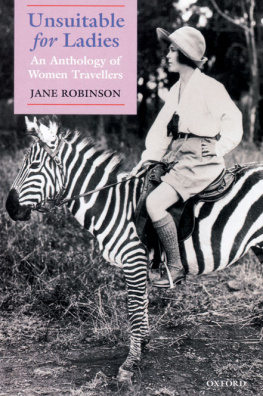

Unsuitable

For Ladies

An Anthology of Women Travellers

Selected by

Jane Robinson

UNSUITABLE FOR LADIES

Jane Robinson first began collecting books at the age of 7, when a local library banned her from using a jam tart as a bookmark. After graduating in English from Somerville College, Oxford, she joined a firm of antiquarian booksellers specializing in travel and exploration. She left bookselling to pursue a writing career, and now, as well as being the author of Wayward Women, Angels of Albion, and Parrot Pie for Breakfast, she is established as one of historys most intrepid women travellersin an armchair. She lives in Oxford with her husband and two sons.

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship,

and education by publishing worldwide in

Oxford New York

Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogot Buenos Aires Cape Town

Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi

Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi

Paris So Paulo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw

with associated companies in Berlin Ibadan

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press

in the UK and in certain other countries

Selection and editorial matter Jane Robinson 1994

Further copyright information can be found on pages 4658

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

Database right Oxford University Press (maker)

First published by Oxford University Press 1994

First issued as an Oxford University Press paperback 1995

Revised 2001

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press,

or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate

reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction

outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department,

Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover

and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Data available

ISBN 0-19-2802011

ISBN 978-0-19-2802019

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Printed in Great Britain by

Cox & Wyman Ltd, Reading, Berkshire

For Richard and Edward

Acknowledgements

I HAVE been inspired, advised, lobbied, and nagged by so many people in the compiling of this anthology that I hardly know where to begin in thanking them. Those included in the Acknowledgements of its companion volume, Wayward Women, must stand responsible to a greater or lesser degree for this book too, and rather than repeat the list here I shall just say a large and general thank-you to them all. I should also like to thank the staff of the British Library, London Library, and Royal Geographical Society for their help and, in particular, those patient souls of the Upper Reading Room, Rhodes House, the Indian Institute, and (most heartfelt, this) the photocopy department of the Bodleian Library in Oxford. To Michael Cox of Oxford University Press I owe a special mention: this book was his idea. Judy Martin, Angus Phillips, Deborah Manley, Robin Hanbury-Tenison, Caroline Schimmel, and Beverley Barrett have all helped it along in various ways, while the greatest help of all (again) was Bruce.

Contents

IT is a surreal picture: in the distance I can see rather a bizarre collection of women, quite a few in dull-coloured Victorian garb with a variety of bonnets, sola topis, and veils; one or two in the heavy habits of the Middle Ages (or even earlier) and several elaborately upholstered in glancing satin finery; there are some in shorts or trousers, perhaps mens; some in medical or military uniform; now and again there is even the odd flowery sun-dress or flash of Lycra to be seen. There must be well over a hundred altogether, and the noise, although muffled by the distance, is considerable. Each seems to be hauling or tugging at something: some sort of rope, I think, and as I trace the tangling lines I realize that they are all connected to me, sitting here in the foreground. I am perching slightly perilously in a fat and complacent armchair and these women, now hazy against the horizon, are lugging me along in it. I am in, it seems, for quite a ride.

This is the brief and strangely familiar vision that occupied my mind as soon as I was asked to edit this anthology. A few years ago, I wrote a book about women travel writers called Wayward Women, so I knew what I was in for. That was supposed to have been a bibliography, but once I had succumbed to the illicit pleasure of reading the books I should merely have been collating, the whole thing changed. These remarkable authors, astonishing company, had led me astray from the well-ordered paths of scholarship towards a much more promising and colourful vista of adventure, unorthodoxy, and general misrule. I was not sorry to go, mind you, and although once I had finished the book I felt exhausted, a little saddle-sore, and frankly rather sick of being on the roadin fact all those things real travellers are supposed to feel on coming home againI soon realized how much I was going to miss my companions. So when the possibility of this book came along, I was delighted and only a little apprehensive. I knew my subjects by now, as I said, and if ever you thought women travellers were just taggers-along, or tourists, or even fierce Victorian viragos too eccentric to stay at home, then I hope what follows will make you think again.

I confess I am malicious enough to desire that the World shoud see to how much better purpose the Ladys Travel than their Lords, and that whilst it is surfeited with Male Travels, all in the same Tone and stuft with the same Trifles, a Lady has the skill to strike out a New Path and to embellish a worn-out Subject with a variety of fresh and elegant Entertainment.

So wrote Mary Astell in her preface to Lady Mary Wortley Montagus so-called Embassy Letters in 1724. And, allowing for customary contemporary over-indulgence (and the authors lumping together of women-in-general, which pernicious habit I shall hence-forth assume myself), I think she has a point. Perhaps the part about mens travel accounts being stuft with Trifles is a touch unfair, but it is true that throughout the sixteen centuries covered by this anthology, womens travel accounts have proved at least no less entertaining than mens, and in a good many instances a great deal more. They are different, certainly, but not, as generations of critics might have us believe, less valid.

Part of this difference must lie in the nature of the journey itself. Women have rarely been commissioned to travel, and so their accounts tend not to be prescribed by the need to satisfy a patron or professsional reputation (except the professional reputation every writer who travelsas opposed to traveller who writesis obliged to uphold). Women can afford to be more discursive, more impressionable, more ordinary. It was a common Victorian argument (and the Victorian age being the golden age of women travellers, as well as of women-in-general, such opinions must be acknowledged) that that is all the lady traveller is fit for: to wander along in her husbands footsteps scribbling down whatever fancy happens to flit into her homely little head. You could not be a real lady and a real traveller. The notion is easily disproven now, with hindsight, and with the surprisingly diverse body of womens travel literature that golden age produced to back one up; what is surprising is that even then it smacked of speciousness to some brave and radical souls. Lady Elizabeth Eastlakeherself an accomplished travellerwas one of them. In an essay (anonymous, for credibilitys sake) discussing a number of new titles by women travellers for a well-respected periodical, she was bold enough to write:

Next page