Table of Contents

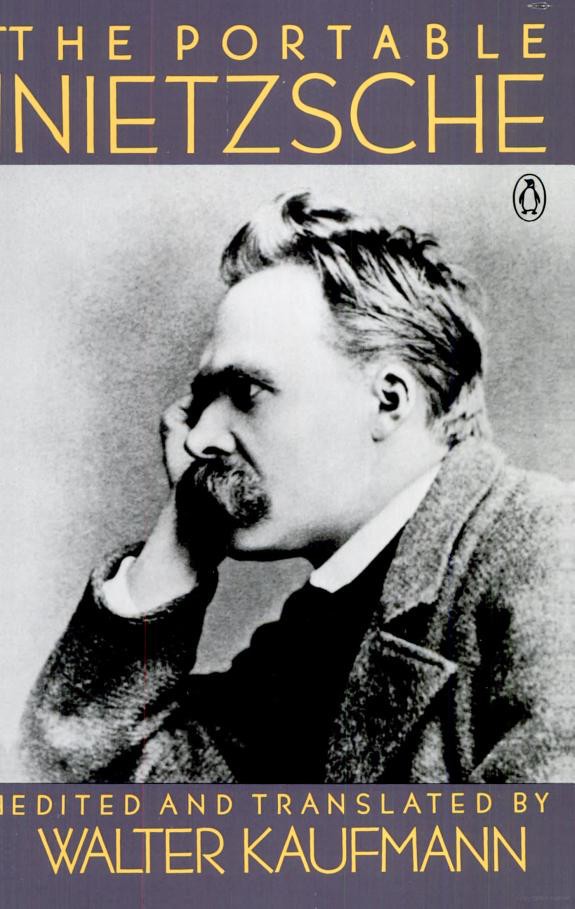

THE VIKING PORTABLE LIBRARY

Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Nietzsche was born near Leipzig in 1844, the son of a Lutheran clergyman. He attended the famous Pforta School, then went to university at Bonn and at Leipzig, where he studied philology and read Schopenhauer. When he was only 24 he was appointed to the chair of classical philology at Basle University; he stayed there until his health forced him into retirement in 1897. While at Basle he made and broke his friendship with Wagner, participated as an ambulance orderly in the Franco-Prussian War, and published The Birth of Tragedy (1872), Untimely Meditations (18736), and the first two parts of Human, All Too Human (18789). From 1880 until his final collapse in 1889, except for brief interludes, he divorced himself from everyday life and, supported by his university pension, he lived mainly in France, Italy, and Switzerland. The third part of Human, All Too Human appeared in 1880, followed by The Dawn in 1881. Thus Spoke Zarathustra was written between 1883 and 1885, and his last completed books were Ecce Homo, an autobiography, and Nietzsche contra Wagner. He became insane in 1889 and remained in a condition of mental and physical paralysis until his death in 1900.

Walter Kaufmann was Professor of Philosophy at Princeton University, where he taught after receiving his Ph.D. from Harvard in 1947 until his death in 1980. He held visiting appointments at many American and foreign universities, including Columbia, Cornell, Heidelberg, Jerusalem, and the Australian National University; and his books have been translated into Dutch, German, Italian, Japanese, and Spanish.

Each volume in The Viking Portable Library either presents a representative selection from the works of a single outstanding writer or offers a comprehensive anthology on a special subject. Averaging 700 pages in length and designed for compactness and readability, these books fill a need not met by other compilations. All are edited by distinguished authorities, who have written introductory essays and included much other helpful material.

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto,

Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R oRL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland

(a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell,

Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park,

New Delhi110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Mairangi Bay,

Auckland 1311, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R oRL, England

First published in the United States of America

by Viking Penguin Inc. 1954

Paperbound edition published 1959

Reprinted 1959 (twice), 1960 (twice), 1961 (three times),

1962 (twice), 1963 (twice), 1964 (twice), 1965 (twice),

1966 (twice), 1967 (twice), 1968 (three times), 1969 (three times),

1970 (three times), 1971 (three times), 1972 (three times),

1973, 1974 (twice), 1975, 1976

Published in Penguin Books 1976

Copyright 1954 by Viking Penguin Inc. Copyright Viking Penguin Inc., 1968 Copyright renewed 1982 by Viking Penguin Inc. All rights reserved.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA

Nietzsche, Friedrich Wilhelm, 1844-1900.

The portable Nietzsche.

Reprint of the 1954 ed. published by The Viking Press, New York,

which was issued as no. 62 of Viking portable library.

Bibliography. p. 688.

1. PhilosophyCollected works. I. Title.

[B3312.E52K3 1976] 193 76-47577

eISBN : 978-1-440-67419-8

The scanning, uploading and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated.

http://us.penguingroup.com

TO EDITH KAUFMANN

Wenns etwas gibt, gewaltger als das Schicksal, So ists der Mut, ders unerschttert trgt.

GEIBEL

Acknowledgments

All the translations in this volume are new, except for some passages that have previously appeared in my Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist. Princeton University Press has generously given permission for their use here. But even these passages have been revised, and, wherever feasible, I have made available other aphorisms and letters instead of reproducing material already available in that book.

In the Introduction and editorial matter too, Princeton University Press has kindly permitted reliance on my Nietzsche. But whereas that book sought to explode the legends woven around Nietzsche and to analyze the break with Wagner, the relation to Lou Salom and to his sister, the final madness, and, above all, his philosophy, psychology, and critique of Christianity, the editorial matter in the present volume has been wholly subordinated to the translations. Nietzsche himself is to speak, and no lengthy editorial reflections seemed worth a corresponding cut in the space allotted to him.

I am greatly indebted to Princeton University for a years leave of absence, which enabled me, among other things, to complete this volume; to Jean Yolton, for generous help with proofs; and to Hazel and Felix Kaufmann, my wife and my brother, for many helpful criticisms, particularly of my translation of Zarathustra.

W. K.

INTRODUCTION

There are philosophers who can write and philosophers who cannot. Most of the great philosophers belong to the first group. There are also, much more rarely, philosophers who can write too well for their own goodas philosophers. Plato wrote so dramatically that we shall never know for sure what precisely he himself thought about any number of questions. And Nietzsche furnishes a more recent and no less striking example. His philosophy can be determined, but his brilliant epigrams and metaphors, his sparkling polemics and ceaseless stylistic experiments, make it rather difficult to do so; and to read him solely to reconstruct the world of his ideas would be obtuse pedantry. At least two things should come first: sheer enjoyment of his writing, and then the more harrowing experience of exposing oneself to his many passionate perspectives. We should not rashly take a well-phrased point for Nietzsches ultimate position, but we often stand to gain if we ask ourselves why it should not be ours. Add to this that few writers in any age were so full of ideasfruitful, if not acceptableand it is clear why he has steadily exerted a unique fascination on the most diverse minds and why he is still so eminently worth reading.

An anthologist can easily re-create Nietzsche in his own image, even as writers of lives of Jesus present us, perhaps as often as not, with wishful self-portraits. Doubtless Nietzsche has attracted crackpots and villains, but perhaps the percentage is no higher than in the case of Jesus. As Maritain has said: If books were judged by the bad uses man can put them to, what book has been more misused than the Bible?