Economics for People and the Planet

ANTHEM FRONTIERS OF GLOBAL POLITICAL ECONOMY

The Anthem Frontiers of Global Political Economy series seeks to trigger and attract new thinking in global political economy, with particular reference to the prospects of emerging markets and developing countries. Written by renowned scholars from different parts of the world, books in this series provide historical, analytical and empirical perspectives on national economic strategies and processes, the implications of global and regional economic integration, the changing nature of the development project and the diverse global-to-local forces that drive change. Scholars featured in the series extend earlier economic insights to provide fresh interpretations that allow new understandings of contemporary economic processes.

Series Editors

Kevin Gallagher Boston University, USA

Jayati Ghosh Jawaharlal Nehru University, India

Editorial Board

Stephanie Blankenburg School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), UK

Ha-Joon Chang University of Cambridge, UK

Wan-Wen Chu RCHSS, Academia Sinica, Taiwan

Alica Puyana Mutis Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales (FLASCO-Mxico), Mexico

Lonce Ndikumana University of Massachusetts-Amherst, USA

Matas Vernengo Bucknell University, USA

Robert Wade London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), UK

Yu Yongding Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), China

Economics for People and the Planet

Inequality in the Era of Climate Change

James K. Boyce

Anthem Press

An imprint of Wimbledon Publishing Company

www.anthempress.com

This edition first published in UK and USA 2019

by ANTHEM PRESS

7576 Blackfriars Road, London SE1 8HA, UK

or PO Box 9779, London SW19 7ZG, UK

and

244 Madison Ave #116, New York, NY 10016, USA

2019 James K. Boyce

The moral right of the authors has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above,

no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into

a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means

(electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise),

without the prior written permission of both the copyright

owner and the above publisher of this book.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN-13: 978-1-78308-875-1 (Hbk)

ISBN-10: 1-78308-875-3 (Hbk)

This title is also available as an e-book.

CONTENTS

Figures

Tables

I am grateful to Tej Sood and Abi Pandey at Anthem Press and to series editors Kevin Gallagher and Jayati Ghosh for encouraging me to bring these essays together in a book. Special thanks to Alejandro Reuss, Chris Sturr and Tim Wise, who published a number of these pieces at TripleCrisis, and to Chris Cox, my excellent editor at Harpers magazine. I thank Arpita Biswas for her valuable assistance in preparation of the manuscript. It is also a pleasure to thank the colleagues with whom several of the essays were co-authored: Peter Barnes ().

Environmentalism needs a new banner: Grow the good and shrink the bad.

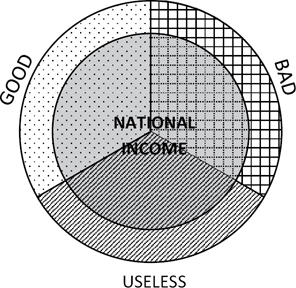

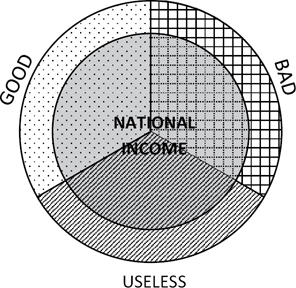

Of course, national income includes many good things, too. Growing food and building homes add to national income. So does public spending on education and healthcare. Unlike oil spills and jails, these really do add to human well-being.

Along with good stuff and bad stuff, national income includes a third category of stuff that is just useless goods and services that neither add to our well-being nor subtract from it but still get counted in the income pie. A prime example is what the economist Thorstein Veblen called conspicuous consumption items consumed not for their intrinsic worth but simply to impress other people and jockey for a higher rung on societys pecking order. These goods and services have zero net effect on national well-being, since for every person who climbs a rung, someone else slips one.

Of course, not all bad or useless things are counted as national income. But neither are all good things. Unpaid work caring for children, the elderly and the disabled doesnt count. Clean air, clean water and climate stability dont count. Free, open-source information and culture dont count.

The national income pie is an odd subset of the good, the bad and the useless. All three slices get lumped together when economists tell us that average income in the United States is roughly $56,000 per person.

Researchers in the emerging field called happiness studies have devised other ways to measure well-being. They find that beyond the level of income that is needed to satisfy basic wants, such as food and shelter, there is little or no correlation between a countrys average income and the happiness of the average person. Past some threshold, increases in the good and bad appear to cancel each other out, and the useless slice of the income pie can get pretty fat.

Since national income isnt the same as well-being, growth in national income isnt the same as improvement in well-being. All too often, this crucial distinction gets lost in acrimonious debates about the relationship between the economy and the environment (see ).

National income (or GDP), denoted by the dark inner circle, counts everything with a price tag no matter whether its good, bad or useless. At the same time, it omits some good things that enhance our well-being as well as some bad things that diminish it. So growth of national income is not a reliable measure of economic progress. Our goal instead should be to grow the good and shrink the bad.

Forty years ago, a report called The Limits to Growth drew attention to the indisputable fact that our planet does not have an infinite capacity to serve as a source for raw materials and a sink for waste disposal. In choosing to call this idea the limits to growth, however, the authors fell into a rhetorical trap that has haunted environmentalism ever since.

The problem is that most people believe that growth is good. When they think about the national income pie, they think about the good slice, unlike environmentalists who think about the bad slice.

Because theyre really talking about different things, proponents and opponents of growth often talk right past each other. And when they assume that the good and bad are inseparable, both sides buy into the myth that there is an inexorable tradeoff between economic well-being and environmental quality. If the good and the bad must go together, they must grow together.

The result: growth wins, and environmentalists play damage control.

To find a way out of this impasse, we need better measures of economic well-being, better public policies and better language.

In the United States, dozens of state-level initiatives are now experimenting with different ways to measure well-being.

In the policy arena, we need to both advance human well-being and protect the environment on which it ultimately rests. This requires not only sound regulations but also true-cost prices to orient investment and consumption decisions to the full range of costs and benefits. In climate policy, for example, although regulations such as fuel economy standards for automobiles can help to promote the clean energy transition, in the absence of a price on carbon emissions there will always be strong incentives to burn cheap fossil fuels.