Copyright 2008 by Telos Press Publishing

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information on getting permission for reprints or excerpts, contact telos@telospress.com.

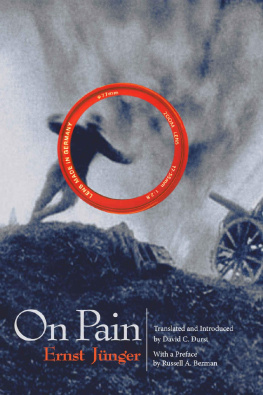

Translated by permission from the German original, ber den Schmerz, in Ernst Jnger, Smtliche Werke , vol. 7, pp. 14391, Stuttgart 1980; 2nd edition 2002. First published in 1934 as part of Bltter und Steine with Hanseatische Verlagsanstalt, Hamburg. Klett-Cotta 1934, 1980 J. G. Cottasche Buchhandlung Nachfolger GmbH, Stuttgart

ISBN: 978-0-914386-59-9 (ebook)

ISBN: 978-0-914386-40-7 (paperback)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jnger, Ernst, 18951998.

[ber den Schmerz. English]

On pain / Ernst Jnger ; translated by David C. Durst.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-914386-40-7 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Pain. I. Title.

BJ1409.J8613 2008

306dc22

2008032925

Telos Press Publishing

PO Box 811

Candor, NY 13743

www.telospress.com

Table of Contents

Russell A. Berman

David C. Durst

Ernst Jnger

Preface to the Telos Press Edition of Ernst Jngers On Pain

Russell A. Berman

Ernst Jngers On Pain belongs to the current of thought of the so-called Conservative Revolution in Germany during the 1920s and 1930s, a deeply pessimistic critique of the society and culture of the Weimar Republic and liberal modernity in general. Building on nineteenth-century precursors, especially Nietzsche, the conservative revolutionaries expressed adamant contempt for the bourgeois values of individualism and sentimentality and generally denigrated the legacy of the Enlightenment, while looking forward to the imminent establishment of a new order made of sterner stuff. Like Nietzsche, they claimed to diagnose the loss of values and a loss of quality in the decadence of modern life. Yet while Nietzsche countered this decline with the myth of the superman as an aristocratic alternative to democratic leveling, the conservative revolutionaries, and especially Jnger, tried to identify a new heroism emerging precisely out of the technological world of the new mass society. If conventional conservatives emphasized a return to the past or, at least, a program to preserve traditions against the eroding forces of progress, the conservative revolution argued that the fundamental transformations at work in contemporary society could lead to an outcome defined by organized power, discipline, and a will to violence. The outcome of progressive modernization would, paradoxically, not be the standard progressivist utopia of free and equal individuals but a regime of authority beyond question.

In the translators introduction to this edition of On Pain, David Durst provides an admirable and encompassing account of the text, its context, and its reception. Jngers essay is a vital document of German thought in the wake of the collapse of Weimar democracy. Durst locates it in relation to the German intellectual-historical tradition and the complex responses to modernity. A stance of heroic realism was viewed as a symptom of an emerging new culture, which Durst traces through important milestones in Jngers writing. On Pain is an indispensable historical document for anyone interested in the underlying political and cultural stakes in the crisis that brought Hitler to power.

Far from the propaganda of the era, Jngers cultural criticism is complex, thoughtful, and often trenchant in ways that distinguish it emphatically from Nazi screeds. No wonder he quickly ran afoul of the Party, as Durst describes. While On Pain does put forward illiberal positions, in some ways it frankly resembles the Critical Theory of the Frankfurt School as it developed in the period and with which English-language readers may be more familiar. It is not that cultural criticism on the right and the left, the Conservative Revolution and the Frankfurt School, converged, but quite understandably they did confront similar problems and pose comparable questions. Intelligent observers described the same social transitions, albeit from distinct perspectives, but with enough similarities to warrant comparisons. Although conventional political thinking still tries to police a neat separation between left and right, we should not be afraid to explore the gray zone in between without leaping prematurely or unnecessarily to an unwarranted assertion of identity.

Jngers rejection of sentimentalist optimism and his insistence on the centrality of painby which he means loss, suffering, and death as well as genuine physical painto the human condition is akin to the dark vision of Schopenhauerian pessimism that suffuses Max Horkheimers thought. The blithe confidence in a collective forward that marked, and still marks, progressivism is no longer on the table. Whatever the consequences of the tragic sensibilityand there are various possible outcomesit precludes the characteristic mentality of the historical optimist, best allegorized by the frozen smile of an emoticon: happy days arent here again. Of course Jnger and Horkheimer draw incompatible conclusions: Jnger predicts a new social type emerging from the existential condition of pain, while Horkheimer takes a historical pessimism as grounds for a possible social criticism.

In addition to this similarity to the melancholy of Critical Theory, another point of contact involves the technological transformation of art. Jngers comments on a new aesthetic sensibility, or rather the post-aesthetic sensibility of photography, bear an uncanny resemblance to Walter Benjamins contemporaneous account, especially in his now canonical Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Jngers On Pain deserves a similar dissemination as an account of the real cultural revolution of the 1930s: Photography, then, is an expression of our peculiarly cruel way of seeing. Ultimately, it is a kind of evil eye, a type of magical possession (40). The new medium elicits a new affect, undermining the cozy hermeneutic community of the literate public sphere, and initiates a reorganization of the relationship of the mass public to political institutions. Finally, one can even argue a Doppelgnger resemblance between Jnger and Theodor Adorno. Both tend to present a historical time-line that emphasizes a fundamental break between laissez-faire liberal and post-liberal, collectivist cultural formations; they both share a post-Weberian suspicion of bureaucracy; and they are both allergic to facile sentimentality. Perhaps most importantly, Adorno and Jnger present uncannily similar treatments of the demise of subjectivity. Jnger describes how humans turn themselves into objects as technology; for Adorno, this objectification is at the crux of a history of alienation. Of course their evaluations of this development could not be further apart. Jnger embraces technological post-humanity as a welcome alternative to effete humanism, while for Adorno the degradation of individuality entails a damaged life, the scars of which preserve the memory of suffering.

As a period document, On Pain is powerful. It provides important evidence regarding the cultural mentality in the wake of the collapse of the Weimar Republic: it makes the strong case for revolution as conservative, rather than as emancipatory, and it ought to be read next to other revolutionary appeals, from Lenins State and Revolution to Bertolt Brechts The Measu res Taken . As a corollary to other documents, including both those of the Frankfurt School on the left and those of Carl Schmitt on the right, it adds an important dimension to our intellectual-historical understanding of the age. However, this edition of On Pain is not undertaken primarily for antiquarian reasons. (An antiquarian collection of historical documents has never been on Telos Presss agenda.) Rather, this remarkable essay has an urgency precisely because elements of its argument shed light on our own cultural condition, three-quarters of a century after its original publication. It is that contemporary relevance of On Pain that is particularly fascinating and that surpasses its documentary value with regard to culture at the end of Weimar democracy.