Philip Wylie - An Essay on Morals

Here you can read online Philip Wylie - An Essay on Morals full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:An Essay on Morals

- Author:

- Genre:

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

An Essay on Morals: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "An Essay on Morals" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

An Essay on Morals — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "An Essay on Morals" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

A science of philosophy and a philosophy of the sciencesa popular explanation of the Jungian theory of human instincta new bible for the bold mind and a way to personal peace by logicthe heretics handbook and text for honest skeptics, including a description of man suitable for an atomic agetogether with a compendium of means to brotherhood in a better worldand a voyage beyond the opposite directions of religion and objective truth, to understanding

Rinehart & Company, Inc.

New York / Toronto

COPYRIGHT, 1947, BY PHILIP WYLIE PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF

AMERICA BY THE FERRIS PRINTING COMPANY, NEW YORK ALL RIGHTS

RESERVED

For My Wife Ricky With Love

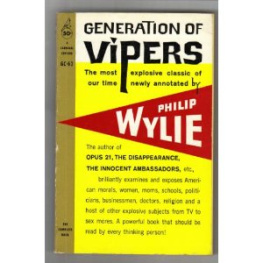

THIS ESSAY REPRESENTS THE ATTEMPT TO DISCLOSE A science of philosophy. I have been preparing to write it for about ten years and written half or more of three books to express these ideas--all of which I set aside unfinished. Generation ofVipers and Night Unto Night--two recent books of mine--were offshoots of the idea I have tried to explain here. The first was a general criticism, the second a novel of specialized rumination. But my main intention has always been neither to lambaste nor to wonder out loud, but to try to teach a logical concept. It is a concept which describes the present chaos of our world--the origin and nature of it--and which offers, I think, a very clear answer to every individual and collective problem.

A large order! A presumptuous undertaking!

The work set aside is evidence of the difficulty I've had even in trying to fill the order. And this Essay is offered with misgiving, with anxiety that I have not expressed the idea adequately for the reader, though with no doubt concerning its authenticity and value. It is not my idea, but only my interpretation of the theories of human instinct developed by Carl Jung from the original work of Sigmund Freud. My interpretation, my description, my derivations, my additions--the further presumption of a layman writing in a scientific field.

There are several reasons for self-election to the task, and the reader will understand this Essay better for knowing them. One is the obscurantism of psychologists.

They need popular translation. Freud's books were, at first, very difficult. Jung's work is all but incomprehensible. I, at least, would never have understood it if the late Archibald M. Strong had not taught me what I could not make out from the text. Other psychologists--Wickes, Jacobi and Gibb--have written books about the theory of instinct but they have not served to bring general attention to it.

And psychologists are deplorably partisan. They school up like minnows and try to devour each other. The "Freudians" are frequently hostile to Adler and Jung. The

"Jungians" often exhibit an attitude of silent and mystical superiority as if it were the adequate substitute for honest debate. Freud, when he was alive, sometimes captained this "team" aspect of his science; and Jung, in my opinion, departs from the very law and order he has discovered to make particular defenses and attacks. Their "followers" have sometimes participated in these passions. It may be human; but it is not helpful to the advancement of a vast, new field of knowledge. Psychology is the science of consciousness--of the mind--of subjectivity--of who man is and what makes him tick. It is, therefore, the science of what makes physicists and biologists tick and of why they bother their heads with the nuclei of atoms and living cells. For a century, the physical scientists have had educated man persuaded that the Ultimate Truth would emerge from their laboratories. They banished religion with the snort of "superstition" and held their work to be "amoral." Lately, some of them have turned nervously to the demand for a moral world. And lately, men like Freud and Jung have shown that religion, among other human enterprises of the mind, has more reality and significance than the materialists guessed.

I came to the study of modem psychology as one versed in the objective sciences.

I had been converted to the atheistic attitude of the scientist from earlier experiences of faith and conviction in Protestant Christianity. And after a long search into psychology I came to feel that the ideas of its scientists suffered from the limitations of their medical background. Physics and mathematics--with which most of them were unacquainted and for which some of them, like Jung, held almost a disdain--offered to their science certain clues and enlightenments of which they made little use. And for the reason that I do understand physics and mathematics, I was emboldened to write about psychology. It has been a considerable journey of the mind from childhood through Presbyterianism and pragmatic atheism to the philosophy of this Essay. And philosophy is what it amounts to.

Psychologists avoid the term; it has a speculative connotation which sheds doubt on their status as scientists. I adopt it, then. It gives me an aegis and an operating permit. I am an amateur, a layman, and I do not even own a university degree, but I have the right to philosophize.

Indeed, since a genuine science of the mind exists, I have a better right than the pedagogues who sit in colleges today, with the rheum of antiquity in their eyes, and beards like Spanish moss, talking about the Platonic and Aristotelian systems as if they were still pertinent, and about Kant, Leibnitz, Descartes, Spinoza and a hundred others as if their theories are still worth serious consideration. Fools! So much is already known about the brain (or the mind) which they have not heard of, or properly considered, that these professors are the equivalent of doctors who try to instruct contemporary medical students in the four biles, in bleeding as therapy, and in the theory that disease is spread by miasms and night air.

Ancient philosophy is irrelevant. And yet--the science of the mind, psychology, makes no adequate effort to replace it. This Essay is such an effort.

From the very beginning of what understanding I have of the theories of instinct in man, I wanted, as I say, to pass on the information. That desire has become an obligation. Readers of Generation of Vipers and Night Unto Night have written more letters than I could answer properly in a lifetime, asking for a statement of the central idea, or the basic position, from which those books derived. And so I have applied myself four times to the response.

First, I undertook to write a simpler description of Jung's psychology than any I had seen. The result was unhappy: prolix and confused. I am not a psychologist.

Furthermore, my own ideas of the subject interposed. Next, I wrote half of a book to dramatize the ideas in an evangelical prose. It is not a good method for the discussion of theory. Then I wrote some five hundred pages of a novel wherein the protagonist was to think out his theory from the experience and event of his life; the reader was to learn, as it were, by the doing. It is a scheme with merit--but I presently perceived that the novel would make its important points after some ten thousand pages and in another ten years of work. And I was becoming impatient. So then I hit upon the idea of a plain essay in philosophy, not confined by scientific methods, not hortative, and not illustrated by fiction. Here it is.

This long bid for sympathy is not innocent. Old readers will remember that, in my lexicon, innocence is the fool's veneer, the sentimental name for ignorance and malice. I have explained how urgently and dutifully I sweat, in the hope that I can shame the reader into making a special effort. To some, the ideas presented here will be familiar.

They will write, as they have written before, "We're way ahead of you, Mr. Wylie." But to others, these thoughts will lie in unfamiliar categories--in categories, even, where they have been taught to resist with all their Strength. Hence some will find the understanding difficult. Some, indeed, will write me that they do not know what I am talking about (and, therefore, that I do not know, either).

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «An Essay on Morals»

Look at similar books to An Essay on Morals. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book An Essay on Morals and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.