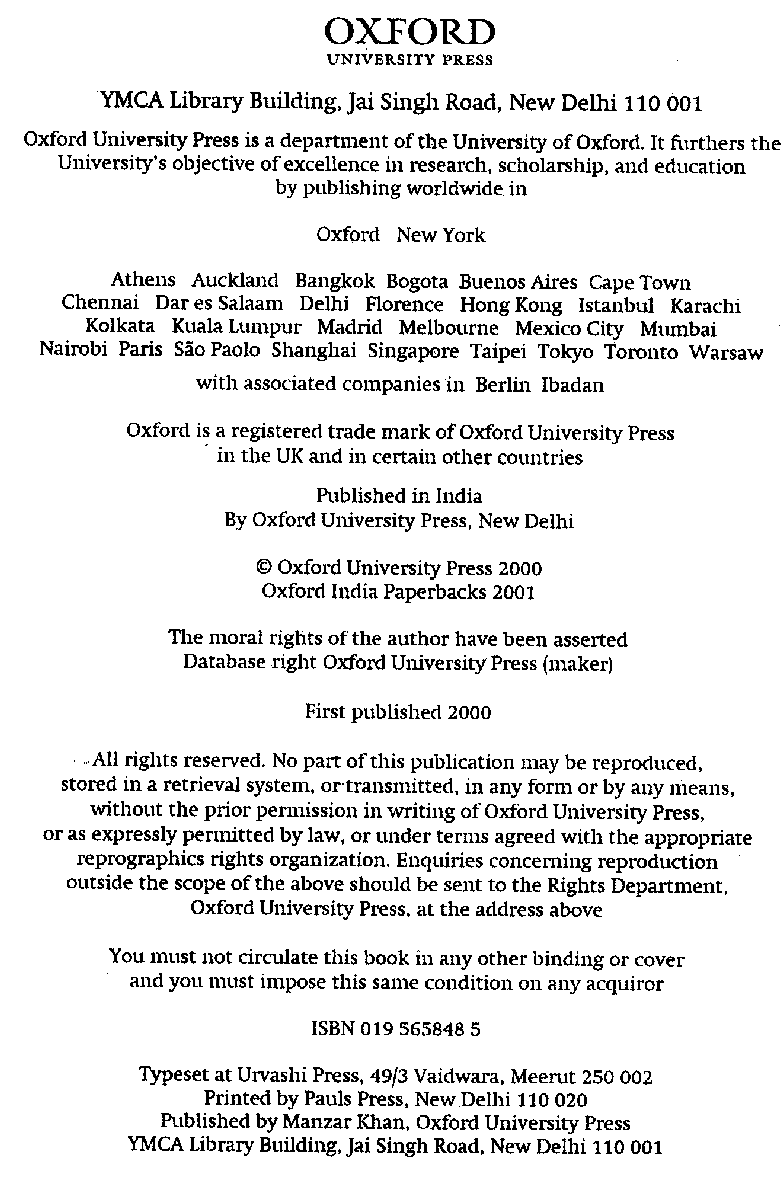

UNTOUCHABLE FREEDOM

UNTOUCHABLE FREEDOMA Social History of a Dalit CommunityVijay Prashad

vi / Acknowledgements

vi / Acknowledgements

Contents

Introduction of illustrationsChapter 1.MehtarsChapter 2.ChuhrasChapter 3.SweepersChapter 4.BalmikisChapter 5.HarijansChapter 6.Citizens

EpilogueGlossaryArchival SourcesIndex

List of IllustrationsSweepers Outside the Town HallEntrance to Valmiki BastiGandhi in Harijan Colony (Courtesy: Nehru MemorialMuseum and Library)Portrait of Bhoop Singh

Introduction

Being an Indian, I am a partisan, and I am afraid I cannot help taking a partisan view.But I have tried, and I should like you to try to consider these questions as a scientistimpartially examining facts, and not as a nationalist out to prove one side of the case.Nationalism is good in its place, but it is an unreliablev friend and vanvunsafe vhistorian.(Jawaharlal Nehru, 14 December 1932).1In the aftermath of the pogrom against the Sikhs in Delhi (1984), in which2500 people perished in a few days, reports filled the capital of the assail-ants and their motives. It was clear from the very first that this was nodisorganized riot and that the organized violence visited upon Sikhswas engineered by the Congress (I) to avenge the assassination of IndiraGandhi. Of the assailants, we only heard rumours, that they came fromthe outskirts of the city, from those urban villages inhabited by Jats andGujjars as well as

dalits (untouchables) resettled there during the Na-tional Emergency (19757). The Peoples Union for Democratic Rights(PUDR) published a pamphlet, just after the carnage, which reported thatthe Bhangismany of them working as sweepers in the corporationcomprised the bulk of the local miscreants who attacked the Sikhs.2 Formany middle-class residents of the city, this news simply reaffirmed theirstubborn conviction that the low castes, being prone to violence anddevoid of any promise or potential beyond that required strict control.Nanki Bai, one of the survivors, told her interviewers in the relief campsthat the metropolitan councillor in her locality had the killing done bythe

kanjars and the

bhangis, both compensated with liquor and cash,since, in her opinion, the educated cant do this sort of thingonly the

neech-log (derogatory for low-status persons) do things like this.3 Suchstatements of prejudice that exempt the educated from culpability erasethe crime of the councillor and the complicity of the bulk of the middle1Jawaharlal Nehru,

Glimpses of World History (Allahabad: Kitabistan, 1939),p. 443.2PUDR,

Who are the Guilty? Report of a Joint Inquiry into the Causes andImpact of the Riots in Delhi from 31 October to 10 November (New Delhi: PUDR,2nd edition, December 1984), p. 3.3Uma Chakravarti and Nandita Haksar,

The Delhi Riots: Three Days in theLife of a Nation (New Delhi: Lancer, 1987), p. 43.

x / Untouchable Freedomclass which benefits from a political system run by authoritarian partiesto maintain economic, social, and political inequality. The screen betweenthe acts of violence and the political structures that work at the behest ofcertain dominant classes enables the latter to disown responsibility formaking violence a means to realize their agenda (as in the excesses ofthe period of the National Emergency).4 The sustained exploitation ofthe working people produces a circumstance wherein some dalits becomeclients of political strongmen to act on behalf of a status quo that op-presses the bulk of the dalits.Among the dalits of Delhi, several young men of the Balmiki com-munity seemed to lead the way in the conflagration. If the Balmikis of-fered fealty to the Congress in the early 1980s, by the end of the decademost indications showed that a set of them had begun to work closelywith the Hindutva movement, first in anti-Muslim actions in Delhi andKhurja (among other places) and subsequently as part of the caravan toAyodhya to participate in the 6 December 1992 destruction of Mir Baqismosque.5 Few realized the gravity of the situation and there are as yetonly rudimentary explanations for the anomalous turn taken by this dalitcommunity as it linked its destiny to the political agencies of the estab-lished order (particularly the Hindutva ensemble, a markedly conserva-tive, misogynist and communal political bloc). If some young men didthe killing, the response of much of the rest of the community rangedfrom tacit to active support for their actions. There is now sufficientcommentary on the assertion of dalits across the country, but this doesnot address the counter-intuitive alliance between activist dalits (at somelevel committed to end the order that enforces dalithood) and the forcesof Hindutva (which are committed to the defence of that very order).6 Asimilar entry of women activists into the Hindu right provoked severaluseful studies of the phenomenon and we are only now getting a glimpse4Vijay Prashad, Emergency Assessments,

Social Scientist, nos. 2801 (Sep-temberOctober 1996), p. 52.5Pradip K. Datta,

et al., Understanding Communal Violence: NizamuddinRiots,

Economic and Political Weekly, 10 November 1990; Uma Chakravarty,

et al., Khurja Riots, 199091: Understanding the Conjuncture,

Economic andPolitical Weekly, 2 May 1992 and my own research during the 19924 period.6Achin Vanaik,

The Furies of Indian Communalism (London: Verso, 1997),pp. 3201.

Introduction / xiof the reasons why some women ally themselves to a programmaticallymisogynist political formation.7 In an ahistorical view of the dalits as aunified entity that

should be opposed to Hindu supremacy in anunproblematic way, this alliance makes little sense. On the other hand, asocial history of the Balmikis reveals the institutional roots of the alli-ance in the colonial municipality where these dalits were hired as clientsof Hindu overseers who exercised inordinate control over their lives.This institutional connection was given an ideological framework in the1930s when these dalits, hired exclusively into the municipality as sweep-ers, adopted and refined an anti-Muslim Hindu identity proffered in thefirst instance by militant Hindus. These dalits, in other words, have along history within the ensemble of Hindutva, even if it did not informthe politics of many of them until recently. That is, most of the Balmikis,until the emergence of the BJP in 1980 tended to live their political liveswithin the Congress, even as they remained wedded to a contradictoryHindu faith (with its anti-Muslim undertones and its humanist overtones)in their private domains. The 1980s enabled many Balmikis to committhemselves to the Hindutva project, particularly since it seemed to prom-ise them the emancipation held off for five decades. One of the indica-tions of this emancipation was the Vishwa Hindu Parishad pledge toerect a temple to Valmiki (the sage of the Balmikis) within the BabriMasjidRam Janmabhoomi complex (this commitment, like many oth-ers made by the Hindutva ensemble to the dalits, comes and goes).HINDUTVA AND BALMIKI CONSCIOUSNESSIn the Saugwan home in Old Delhi on 28 March 1993, Tara Chand endedan emotional conversation with the plaintive refrain,

hum aur kya karsakte the (what else could we have done)? He, his friends, and family hadjust finished collectively telling me about a fracas of 18 June 1978. Intheir version, a young Muslim boy from the neighbourhood urinated inthe narrow alleyway that led into their Kalan Mahal locality. SomeBalmikis asked the boy not to use the drain as a latrine, since, as MadanLal emphasized, both our women walk on this road. The road is atight lane with houses on one side and a high wall on the other, withsurface drains along its edge to bear the refuse from the homes to thesewer. The conflict was less about the urine and more about the affront tothe dignity of the women by public urination. The Muslim boy was beatenby several Balmikis as a prelude to an evening of mayhem. Several Mus-7

Next page

UNTOUCHABLE FREEDOMA Social History of a Dalit CommunityVijay Prashad

UNTOUCHABLE FREEDOMA Social History of a Dalit CommunityVijay Prashad

vi / Acknowledgements

vi / Acknowledgements