The Sea

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM BLOOMSBURY

Disparities, Slavoj iek

Dying for Ideas, Costica Bradatan

Glimpse of Light, Stephen Mumford

A History of Animals in Philosophy, Oxana Timofeeva

Kafka, Howard Caygill

Slow Philosophy, Michelle Boulous Walker

What Is Philosophy for? Mary Midgley

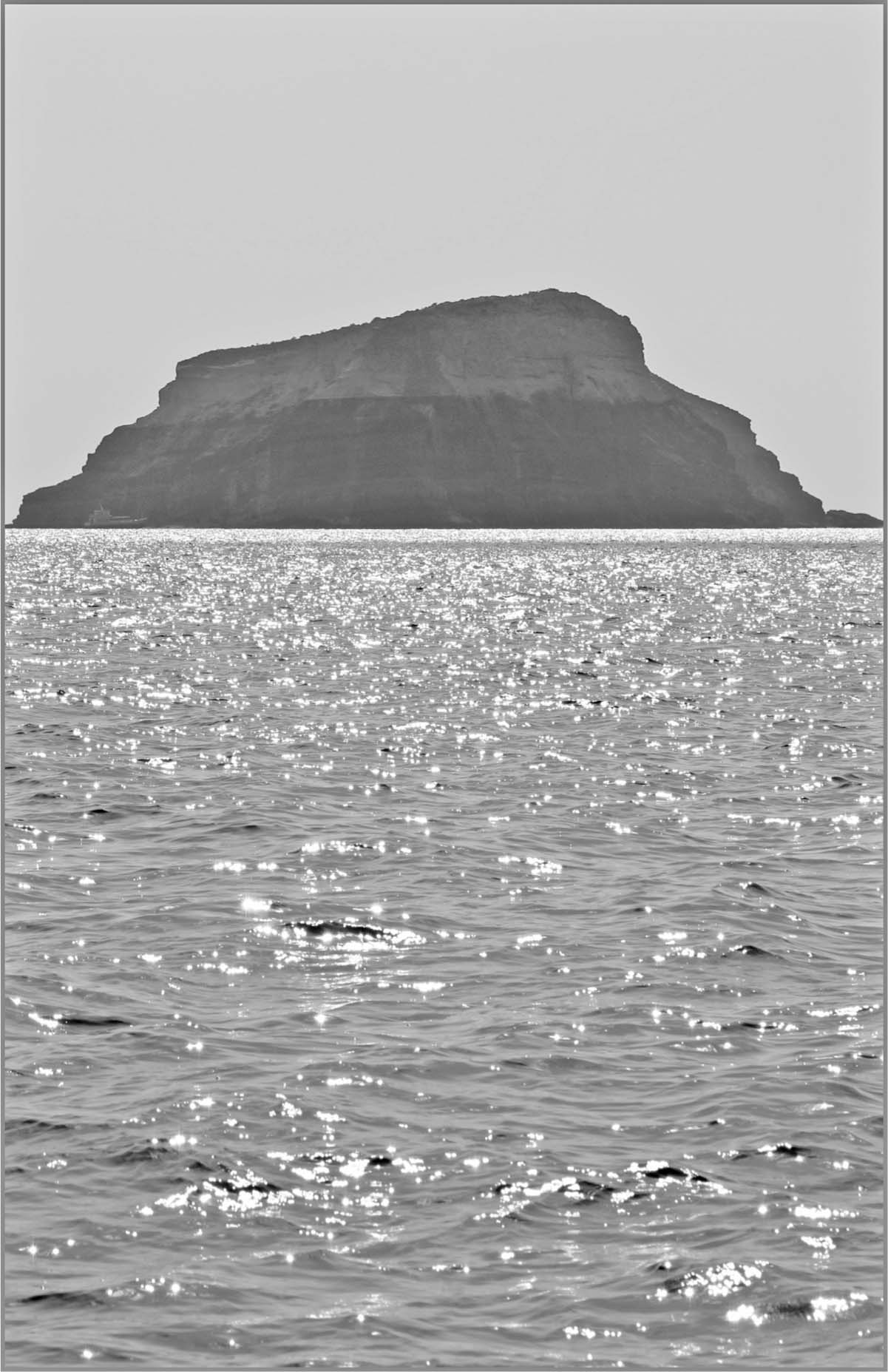

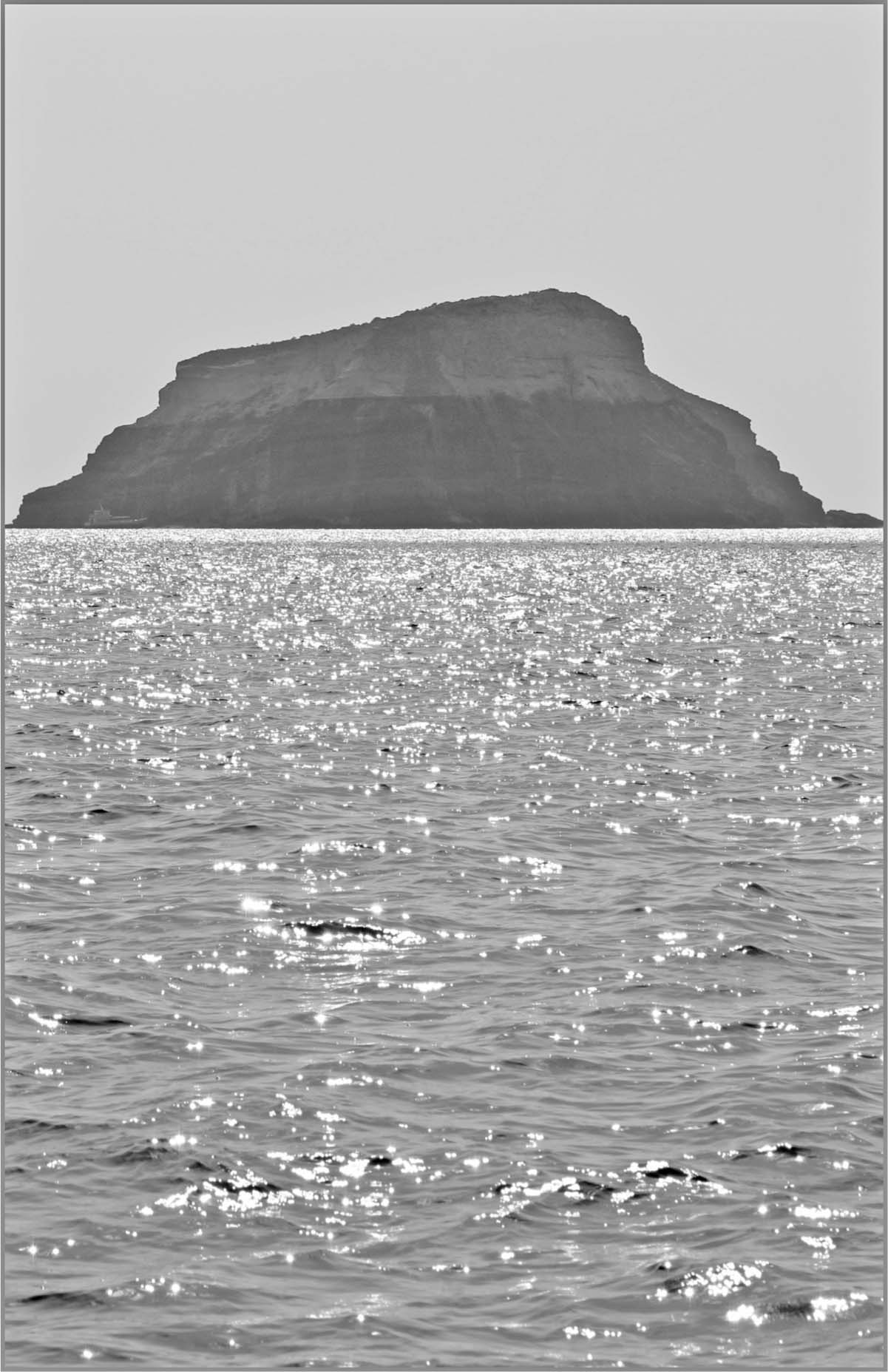

1 Aspronisi, the White Island, west of Thira (Santorini).

For Davidcito and Vanessa,

and for two who have recently made

the immense sea journey,

Isabel Salom and Luca David

Malachi Mulligan to Stephen Dedalus:

God, he said quietly. Isnt the sea what Algy calls it: a grey sweet mother? The snotgreen sea. The scrotumtightening sea. Epi oinopa ponton. Ah, Dedalus, the Greeks. I must teach you. You must read them in the original. Thalatta! Thalatta! She is our great sweet mother. Come and look.

JAMES JOYCE, ULYSSES

The sea will have her way.

EVANGELIA MATSADOU

Which is the best of Shakespeares plays? I mean in what mood and with what accompaniment do you like the sea best?

JOHN KEATS, LETTER TO JANE REYNOLDS, SEPTEMBER 14, 1817

Here lies one whose name is writ in water.

EPITAPH OF JOHN KEATS

Contents

Friends who volunteered to read this book in manuscript urged me to say something up front about its strange itinerary. And the itinerary is strange, if only because it sets out from two very different points of departure.

The first starting point of the book was my readingdecades ago nowof Sndor Ferenczis Thalassa: A Theory of Genitality (1924). That remarkable book expanded Freudian psychoanalytic theory in the direction of what Ferenczi called bioanalysis. I was gripped by the main theme of bioanalysis, which is what Ferenczi called the thalassic regressive undertow. By that he meant that the sea, celebrated by poets and scientists alike as the original site and source of life, eventually draws all life back to itself. All that lives ends by drowning, as it were, in what Hegel called the universal element. Ferenczi also reflected on the way in which the gestation of the mammalian fetus in amniotic fluid, the saline solution in which we humans too spend our initial months, can be understood in phylogenetic terms as the need to find an ersatz for the sea. These early months continue to have effects on the remainder of our lives, he argued; sleep and sex, for example, cannot be understood apart from our having been cradled in the amnion. And what Freud after 1920 called the destruction-and-death drives, Ferenczi added, may be interpreted as the seas imperious summons to return whence we came.

Love, death, and the sea? It was difficult for a young philosopher not to be interested.

Yet the present book has a second starting point, if it is possible for beginnings to double in this way. Although I was born in a landlocked state, I soon traveled to the seashore, and like many human beings I never stopped going there. I did what everybody does at the sea: I swam, sunbathed, collected sea wrack, explored the shoreline, ate ravenously, and slept soundly. Often enough, when the sea allowed it, I simply floated on my back and let sundry thoughts and lines of poetry drift across my mind. In later years I came to appreciate what Herman Melville meant when he said that meditation and water are wedded for ever.

Meditation? An old-fashioned word. The dictionaries say that to meditate is rare, at least when it means to contemplate, ponder. Yet they accept as more current the meaning to dwell in thought, to muse, to reflect, to cogitate. My own form of meditation is not so well-structuredmy friends assured me of thatand it is tied to no belief or religious practice. It is, I must admit, highly associative and intuitive, responsive rather than argumentative, perhaps even passive, as passive as floating on ones back. In recent years a number of French thinkersMerleau-Ponty, Levinas, and Derrida among themhave stressed the importance of such passivity, however. In this they may have been following the lead of Heideggers Being and Time, which emphasizes that existence is moved rather than self-moving: Bewegtheit, rather than Bewegung, is the guiding concept of fundamental ontology.

My own meditation on the sea reflects this passivity, but also my resistance to it, a resistance that takes the form of research and analysis. Yet no amount of strategic reading or painstaking research and analysis can explain precisely why the thinkers and writers who appear in my book are the only ones who appear there. Why Ferenczi rather than Jung or Rank? Why Schelling and Hegel rather than Kant? Why Hlderlin and Nietzsche of all the thinkers and poets of the sea? Why Melville rather than Conrad? And why, of all her novels and essays, Virginia Woolfs The Waves?

I find no ready answers to these questions, to my friends and my own chagrin. Except to remark that one of the clearest signs of human finitude, a sign that is seldom read, is the set of choices we all make in what is after all our very limited reading. It is as though we do not choose those works we read; rather, they choose us. No amount of research or scholarly discipline can alter very much the way these choices go. They follow submarine currents and undertows. All I can hope is that the works that have chosen me in this encounter with the sea prove to be rich resources for my readers as well.

I will defer detailed discussion of the chapters of this book until the Introduction, but let me add a word about the styles of the book, which, conforming to the double starting point, are at least two. I allow myself the old-fashioned and rather puffed-up words philosophical encounter, meditation, and reflection in order to describe one of the styles of the book, a style that reflects more my personal experiences at, on, and in the sea than any wish to write a scholarly work. And yet some of the chapters, such as those on Ferenczi, are purely expository, if only because the ideas developed in them are so difficult. Some of the chapters, such as the first, Let Ourselves Be Cradled, reflect a style that Maurice Blanchot described as fragmentary writing. Here the waves of writing are not as predictable as they are in expository writing, and readers may well have the feeling that they are as adrift as I am. Yet both the expository and the fragmentary styles serve the same purpose, hoping to develop styles of meditation that do justice to the sea, which will have her way, not ours. To repeat, Melville tells us that meditation and waterand he means principally the salt seaare wedded for ever, and no doubt he chose his verb quite carefully. Philosophers have increasingly abandoned the sea to marine biologists, adventurers, and poets, preferring the security and the logic of the lee shore. Poets, occasionally joined by psychoanalysts, take us back to the sources, however; that is, to the sources that feed the sea, the sea that evaporates to cloud, the cloud that releases rainfall, and the stream that rushes to the sea, the source of all sources.

Next page