KARL MARX

Karl Marx

Philosophy and Revolution

SHLOMO AVINERI

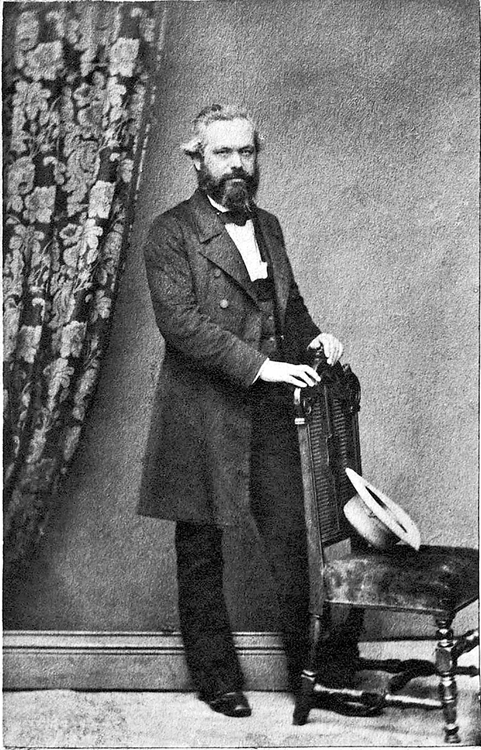

Frontispiece: Karl Marx, around 1860

Copyright 2019 by Shlomo Avineri.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations,

in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S.

Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written

permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational,

business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail

(U.S. office) or (U.K. office).

Set in Janson type by Integrated Publishing Solutions.

Printed in the United States of America.

ISBN 978-0-300-21170-2 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018963640

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

(Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

Preface

B ECAUSE OF HIS DARK COMPLEXION , Karl Marx was nicknamed by his friends and colleagues Der Mohr (The Moor), as in Othello. This is how Friedrich Engels always addressed him in their voluminous correspondenceLieber Mohr. This was also how Marx himself occasionally signed his own letters.

Nobody, of course, thought Marx was of Moorish or Arab descent; the playful orientalist nickname was, however, a constant, even if surreptitious, reminder of his familys Jewish background. As far as we know, it never became a subject of public discussion, yet its presence is undeniable.

In his magisterial essay Benjamin Disraeli, Karl Marx, and the Search for Identity, Isaiah Berlin eloquently argued that Marxs passionate advocacy for the proletariat has to be ascribed to his Jewish ancestry: It is the oppression of centuries of a people of pariahs, not of a recently risen class, that is speaking in him. Others have claimed that it was the tradition of Old Testament prophecy that found expression in Marxs messianic vision. Perhaps; but in the cauldron of nineteenth-century revolutionary movements, many who had no Jewish background also shared this political messianism, which could as easily have its roots in the Christian as in the Judaic tradition.

Marx cannot be seen as a Jewish thinker, and his knowledge of matters Jewish was minimal. Nor did his biography follow any pattern of Jewish life. Yet his Jewish origins and background did leave significant fingerprints in his work, some of them obvious and others less so. One of the aims of this book is to put this background in its proper and balanced perspective.

Marx was a revolutionary thinkerphilosopher, historian, sociologist, economist, current affairs journalist, and editornot a revolutionary activist. With the exception of less than two years during the revolutions of 184849, he was not involved in revolutionary activities, and even that was mainly as a newspaper editor. Any biography that would try to divorce the flesh-and-blood Karl Marx from the iconic Karl Marx will have to focus mainly on his writings, which document his intellectual development, with all its nuances, in a much more fascinating way than the canonical image in which he is mostly presented.

This may not be an easy task. Marxs canonization and the codification of his thoughts into a doctrine called Marxism began quite soon after his death, led by Engels, who became the official executor of his literary legacy. Attuned to the political needs of the ascending German Social Democratic Party in the late 1880s and early 1890s, Engels was responsible for making many of Marxs works known to a wider public. This included republishing long forgotten writings, as well as deciding which of Marxs numerous manuscripts should be published. This editorial work also involved decisions about which of Marxs manuscripts would not be published. Consequently, many of these manuscripts were first published only half a century later, in the 1920s and 1930s; and because of the turmoil of European history at that time they did not become widely known until after World War II.

Engels also provided prefaces to Marxs writings edited and published by him, and they helped to present Marxs thoughts as a closed theoretical system, sometimes elevating occasional comments on current affairs into ex cathedra doctrines, as if enunciating eternal verities. Most of Marxs seminal writings have reached twentieth-century readers through these editorial efforts of Engels, and it can be easily shown that in many cases political writers, both socialists and anti-socialists, as well as scholars, attribute to Marx views and positions that originate in prefaces by Engels rather than in Marxs own texts. What is usually called Marxism is what Engels decided to include in the corpus and the way he interpreted it. The post-1917 schism between Social Democrats and Communists further exacerbated these intellectual gladiatorial fights over interpretation of what has sometimes become an ossified set of dogmas.

Since Marxs fame has been mostly posthumous, this biography will try to present him in the actual historical contexts, intellectual and political, in which he lived and acted. Liberating the real-life Marx from the canonization in which his thought has been wrapped helps to discover a much more exciting and compelling thinker who grew with his time and learned from the history he was living through.

When taken off his pedestal, Marx appears to grow in stature. Despite his sober assessments and setbacks, he never lost his belief in a redemptive future, anchored in the internal dialectics of historical development, regardless of how long it will take to arrive and how differing and ever-changing its form might be. And in this belief he was proven both right and wrong.

KARL MARX

1

Jew? Of Jewish Origin? A Converted Jew?

A DAUGHTERS TESTIMONY

L ESS THAN TWO MONTHS after Karl Marxs death in London in March 1883, his youngest daughter, Eleanor (Tussy) Marx-Aveling, published in the socialist journal Progress an obituary of her father. In the second paragraph she wrote: Karl Marx was born at Trier on May 5, 1818, of Jewish parents. His fathera man of great talentwas a lawyer, strongly imbued with the French eighteenth-century ideas of religion, society, and the arts; his mother was the descendant of Hungarian Jews who in the seventeenth century settled in Holland.

Marxs Jewish background was of course common knowledge, but he never referred to it publicly himself, certainly not in the way described here. Yet explicitly bringing up her fathers Jewish origin in such a prominent way should not come as a surprise from Eleanor. Of Marxs three daughters, she was the best educated and the most active politically. She was also an essayist and a prolific translator of both literary and political works: she translated Flauberts Madame Bovary

Next page