Hegels Realm of Shadows

Hegels Realm of Shadows

LOGIC AS METAPHYSICS IN THE SCIENCE OF LOGIC

Robert B. Pippin

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2019 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2019

Printed in the United States of America

28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-58870-4 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-58884-1 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226588841.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Pippin, Robert B., 1948 author.

Title: Hegels realm of shadows : logic as metaphysics in the Science of logic / Robert B. Pippin.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018014784 | ISBN 9780226588704 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226588841 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich, 17701831. Wissenschaft der Logik. | Logic. | Philosophy, German.

Classification: LCC B2942.Z7 P545 2018 | DDC 193dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018014784

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

CONTENTS

I owe a very great debt to the Friedrich von Siemens Foundation of Munich, and to its director, Heinrich Meier, for a generous fellowship that allowed me to spend the year in Munich in 201213. I had begun a book on the Logic two years before, and this fellowship allowed me an invaluable opportunity to begin the writing of several chapters and to intensify my reading of the literature on Hegels most important book. I am especially indebted personally to Heinrich and Wiebke Meier for many acts of kindness and generosity to me and my wife during our stay there.

I am also grateful to many conference and colloquium audiences over the past eight years for patiently helping me work my way through several early versions of chapters, and for several years of dedicated graduate students in a series of seminars about the Encyclopedia Logic and The Science of Logic. Earlier, in some cases much earlier, and very different or truncated versions of chapters have appeared elsewhere, and I am grateful to editors either for permission to retain copyright for publication of the versions in this book or for permission to reprint here passages of, specifically, The Oxford Handbook of Hegel, ed. D. Moyar (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017); Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, vol. 114, part 2, 2014; a German version of part of is collected in Kant on Persons and Agency, ed. Eric Watkins (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018).

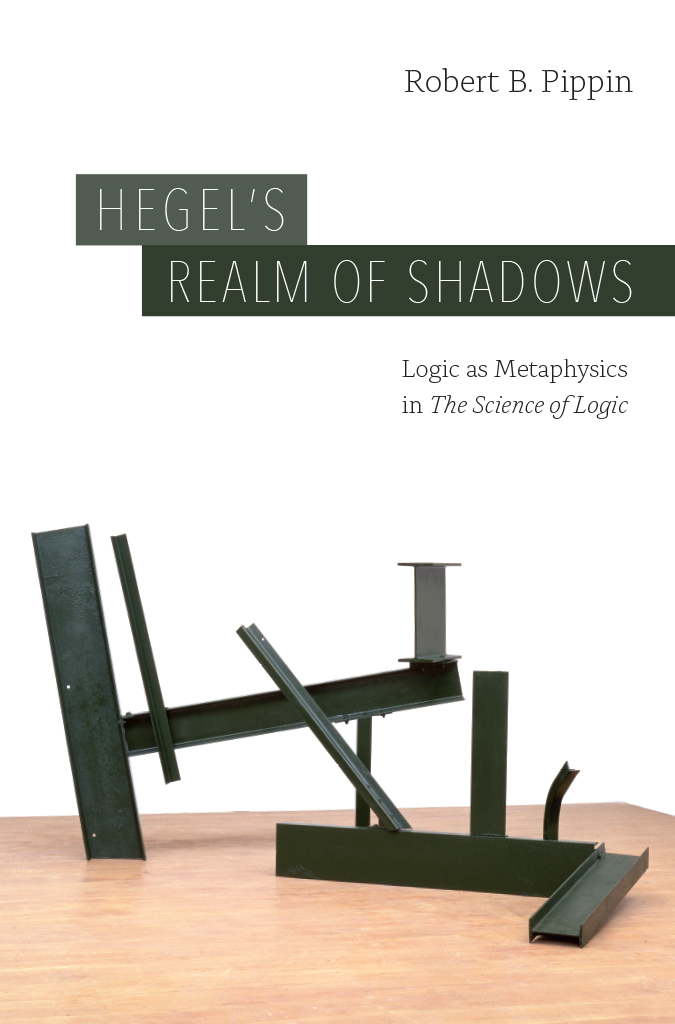

The cover photo is of Anthony Caros great piece, Sculpture Two. I take it to be a visual way of making the Hegelian point that an abstraction can be concrete, even weighty, and that what appears to be a contingent assemblage of parts can be a dynamic, organic unity, no aspect of which can be subtracted, to which nothing can be added. I am most grateful to Barford Sculptures in London for permission to reprint the photograph, and to Michael Fried for many discussions about Caros sculptures.

Finally, I am grateful yet again to my friend Terry Pinkard for invaluable and detailed comments on the penultimate draft of the book. The anonymous readers for the University of Chicago Press were also generous and very helpful.

INTRODUCTION: THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE SCIENCE OF LOGIC

Reason has insight only into what it itself produces according to its own design. (Critique of Pure Reason Bxiii)

Critical philosophy did indeed already turn metaphysics into logic but, like the subsequent idealism, it gave to the logical determinations an essentially subjective significance out of fear of the object. (SL 21.35)

Logic and Idealism

Hegel repeatedly said that the core of his philosophy, what everything else depends on,

Hegel also says frequently that a science of logic is a science of pure thinking. This must be understood in the context of what we designate as German Idealism. This idealism, at least the thread that travels from Kant through Fichte to Hegel (Schellings idealism is another issue), has three components. The first is the claim that a priori knowledge of the world, the knowable, requiring us to admit that we do not know objects as they fully are in themselves. And an even more extreme idealism would hold that the mind (or the divine mind active in us) creates its own objects by thinking them, which certainly explains how pure thinking could on its own determine the nature of the real. But it does so at the price of great implausibility.

But there is clearly a question to be answered, and such an answer would be the third component of idealism: how could the first two components possibly be true, if the standard versions of the third component are not true too. One interpretation of Hegel on this point is that these two claims can be jointly assertable only if what there really is, the really real world, what is accessible only to pure reason alone, is itself thought, thinking momentssomething like the Absolutes or Gods thinking itself, an inherent, evolving noetic structure. This is sometimes what scholars are insisting on when they insist, against what they perceive as nonmetaphysical readings, that Hegel was certainly (and for many quite obviously) a metaphysician in just this sense. The nature of the real is an intellectual entity. is that we are talking not about any dependence but about an identity (a speculative identity to be sure) between the forms of pure thinking and the forms of being. It will take a while to exfoliate the terms of such an identity claim.

I note immediately that there is a widespread view that this Hegelian project (in any possible interpretation of it) is doomed from the start, that there is not and cannot be such a topic as pure thinking. Since the Jena romantics and Hegels contemporary, Schelling, began this line of attack, it keeps reappearing in the European tradition down to the present, with the popularity of new realisms and speculative materialisms and the influence

As will be obvious in the next two chapters, I think we start heading in the right direction if we consider the Logics project under the rubric John McDowell introduced in the second lecture in Mind and World,

The context of McDowells discussion is perception and perceptual knowledge claims, so it is of limited use for the details of The Science of Logic, which is some sort of claim to a priori knowledge. Moreover, the relation of thinking and the thinkable in the Logic faces a problem not germane to McDowells concerns in his book. The problem is: how to account for the determinate moments of any thinking of the knowable, such that they count as the determinate moments of the knowable itself?(what pure thinking is), and he means a pure thinking that is a knowing, one that is onto objects as they are. In the logic of the day, that means he is talking primarily, but not exclusively, about judgments. (Not exclusively because he thinks the nature of judgments cannot be isolated from an account of concepts and inferences.) Pure thinking is thinking without dependence on the deliverances of sensibility, without reliance on experience. Traditionally the question inspired by the very formulation of such a project arises naturally: What, if anything, objective can be known just by thinking, without reliance on empirical experience? In the long tradition of pre-Kantian Western rationalism, that question was often understood to be asking: Are there

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).