To Mr and Mrs C.N. Reddy

Chapter One

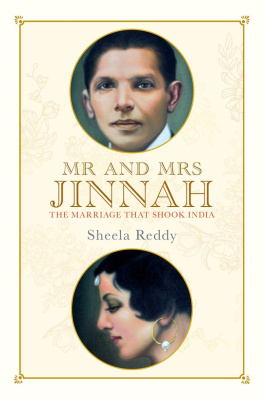

After keeping the world guessing for two years, on a hot April evening in the year 1918, Mohammed Ali Jinnah married Ruttie Petit, the only daughter of a rich Parsi baronet. He was a cold, reserved man of nearly forty-two and had so far lived according to his own carefully laid plan, arriving after two decades of exertion exactly where he had intended to be: one of the best-paid lawyers in the country, an elected member of the viceroys Imperial Legislative Council; the tallest leader in Muslim politics and well on his way to becoming the most important Congress leader. Until now, marriage had not figured in his plans, especially not to a rich, society girl less than half his age. But once he made up his mind to marry Ruttie, he set about it with his usual stoic resolve, unflinching in the face of the innumerable little humiliations and ridicule, skilfully dodging the traps set in his path and planning every step of the way in his diligent, thorough manner.

He began straightforwardly enough, taking his marriage proposal directly to Rutties father, with whom he was staying as a guest during that holiday. Rutties father, Sir Dinshaw Petit, was a stout, plump-faced, amiable man around Jinnahs age who had inherited a vast fortune. He usually took his family abroad for holidays, either to London or France, where he owned an estate on the French Riviera almost as large as the Prince of Monacos and the King of Belgiums. But since the War had started, the Petits had been unable to travel abroad and instead moved to the hills whenever they needed a break, travelling with their four childrenRuttie, followed by three boysand their army of cooks, table boys, maids, governess, tutors, nurses, horses and dogs and any house guests they could assemble. Sir Dinshaw was a genial host and liked to collect eminent people around him; neither his palatial sea-facing mansion on Malabar Hill nor his hill estates in Poona and Matheran were ever short of guests. He had known Jinnah since before Ruttie was born and was very fond of him, as was the elegant Lady Petit, so invitations to visit them were never lacking. But this was probably the first time that Jinnah had accepted the Petits invitationand certainly the last time he ever stayed with them.

Sir Dinshaw admired Jinnah, who was very popular among his contemporaries because of his impressive personality and stout-hearted nationalism. It is unlikely that Jinnah returned the compliment. Sir Dinshaw belonged to a family of Parsi merchants well known for their business acumen and philanthropy. His grandfather was a self-made millionaire, pioneer of Bombays cloth industry, and a leading benefactor of Parsis; his father ran a colossal business empire, including nearly a dozen cloth mills, and with such a thorough, practical knowledge of the spinning and weaving industry that he wrote a two-volume tome on the subject. When Sir Dinshaw was only twenty-two, his father died leaving him to fill his shoes as best as he could. Six years later, he inherited his grandfathers title as well, although his father had not been the eldest son, thereby cutting out of the succession several cousins who considered themselves more deserving. It gave him, besides his vast fortune, a deep sense of his own importance as well as a lasting insecurity. He was quick to take offence and, according to the British, vain. They refused to take him seriously, with a high-ranking official even pointing out during a cross-examination in court by Jinnahin a case involving rigging in a municipal election by British officials to keep out an anti-government candidatethat it was really Sir Dinshaws vanity that drove him rather than any strong political conviction, and implying that the baronet would fall in line with any British-inspired scheme so long as they pandered to his conceit and sense of self-importance. It was an opinion shared by the nationalists as well, with the Parsi firebrand Sir Dinshaw Edulji Wacha deploring his nomination to the viceregal council because, as he later wrote to Dadabhai Naoroji, Sir Dinshaw Petit was totally ignorant of public affairs and the British should have shown some balance of the aristocracy of wealth and intellect.

In his bid to outshine the other fabulous homes rising up on Malabar Hill, he poured lakhs of rupees into renovating Petit Hall, the sea-facing marble mansion that he inherited from his grandfather at the bottom of Malabar Hill. Petit Hall was already an imposing palace, with its Grecian pillars and fountains, and sweeping stairways made of the most expensive imported marble, built by his grandfather as a second home to host his grander receptions. But once Sir Dinshaw took over, he rebuilt it on an even more ambitious scale, adding new wings with suites of bedrooms overlooking the sea, tall shade trees and lawns which almost touched the waves. The gardens were filled with imported French flowers and all of this was on land he reclaimed from the sea, and surrounded by a vast park. Inside were dozens of crystal chandeliers, Louis XV tables and chairs, ancient Ming vases, ceramic potted palms and Persian carpets, all in such good taste that one remembers only the beauty and forgets the cost, as poet and nationalist orator Sarojini Naidu, a frequent house guest at Petit Hall, wrote home to say. But he probably could not resist boasting of the cost of such understated elegance, if we can presume that Sarojini got her figures on the cost of furnishing a single room in Petit Hall from her host: The day drawing room alone, that is used only for receiving grain merchants and students and stray poets, cost 80,000 rupees to furnish. The tapestry alone used to cover a set of eight chairs in this room cost 20,000 rupees.

He also entertained lavishly, keeping one of the best tables in Bombay, with his chefs providing the finest of four different cuisines. His annual Polo Ball was the highlight of the Bombay season, and the size and scale of his garden parties were the envy and delight of Bombays high society. To be fair, in this Sir Dinshaw was only following in the footsteps of his grandfather. The old baronet had famously hosted a fancy dress ball at Petit Hall for the Duke of Edinburgh, turning out for his own party in the costume of the Persian king, Shapurji. But being an astute old man, the previous baronet was able to use his grand receptions as stepping stones to a successful political career. Unlike his grandson, Sir Dinshaw the First was able to extract rich dividends from his extravagant entertaining, earning himself through them a string of public honours, including the office of Sheriff of Bombay and a knighthood, followed three years later by a baronetcy. The first baronet, also called Sir Dinshaw Petit, was an unashamed and energetic British-pleaserserving on committees to organize public festivities in honour of the marriage of the Prince of Wales, delivering farewell addresses to departing officials and erecting statues in their memory, even organizing on one occasion when the Prince of Wales was seriously ill, a solemn ceremony in all the fire temples to pray for his recoverywithout ever losing his clout and eminence within the Parsi community.