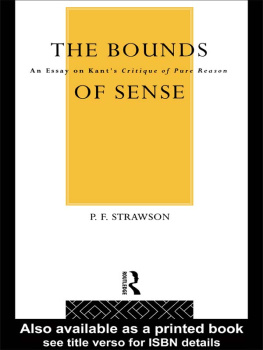

Things That Bother Me

Death, Freedom, the Self, Etc.

GALEN STRAWSON

New York Review Books New York

New York Review Books New York

This is a New York Review Book

published by The New York Review of Books

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Copyright 2018 by Galen Strawson

All rights reserved.

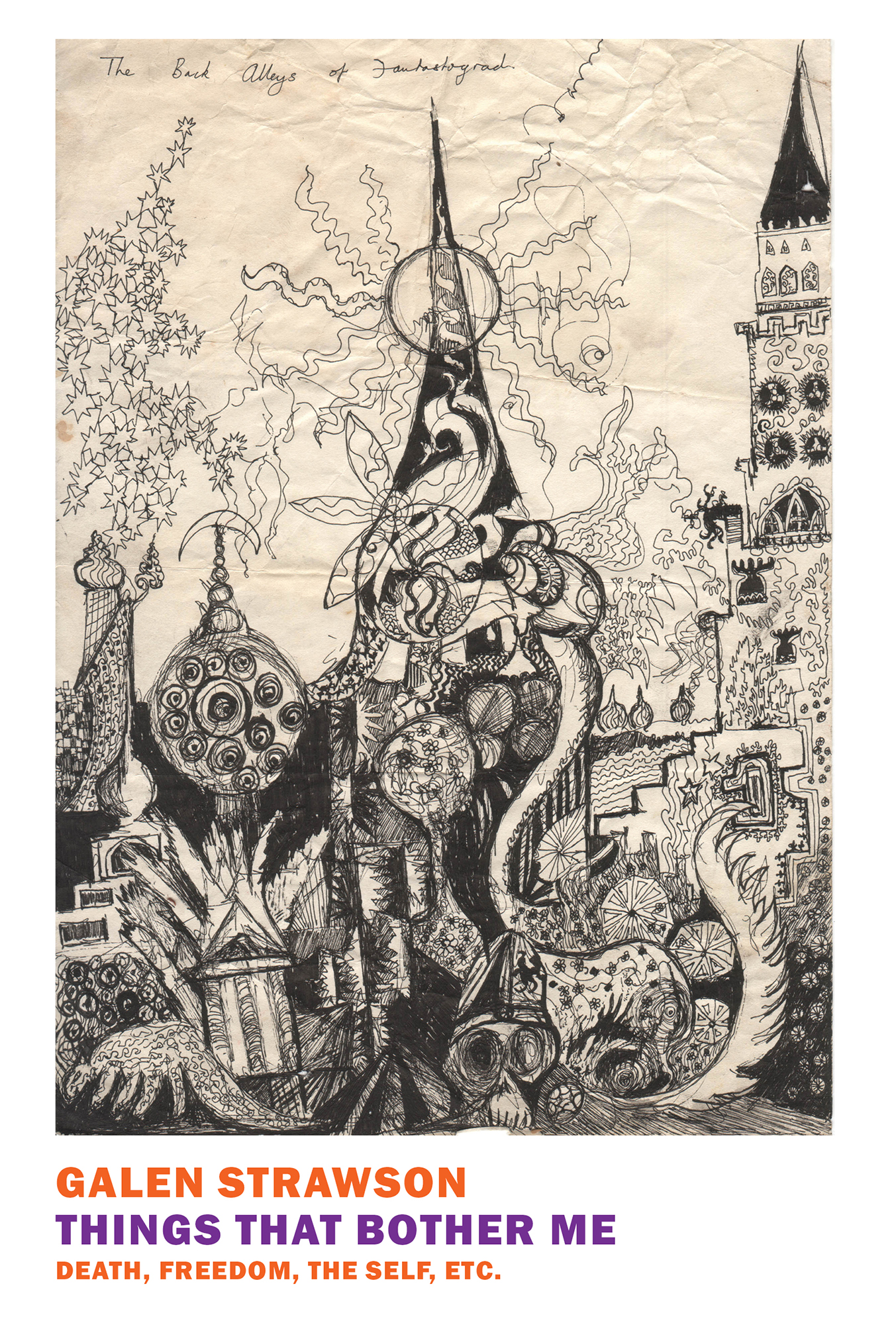

Cover illustration: Simon Halliday, The Back Alleys of Fantastograd, c. 1967

Cover design: Katy Homans

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Strawson, Galen, author.

Title: Things that bother m. : death, freedom, the self, etc. / by Galen Strawson.

Description: New York Cit. : New York Review Books, 2018. | Series: New York Review books classics

Identifiers: LCCN 2017052996 (print) | LCCN 2018001597 (ebook) | ISBN 9781681372211 (epub) | ISBN 9781681372204 (alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Philosophy, British20th century. | Philosophy, British21st century.

Classification: LCC B1667 (ebook) | LCC B1667 .S3771 2018 (print) | DDC 192dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017052996

ISBN 978-1-68137-221-1

v1.0

For a complete list of titles, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:

Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

Contents

Introduction

S OME OF US get hold of the idea of infinity when were very young. Its not that rare, especially among children who love numbers; it happened recently to one of my grandsons. Infinity is troubling at any age, especially if it leads on to the notion of eternityas it so easily canand then links to the idea of deathas it so naturally does. But I think it may strike with unique force in childhood. This, in any case, is what happened to me, by the time I was four, although there hadnt been a death in my family, and although it was, in child-time, long before the school friend to whom I was engaged to be marriedshe and I were fiveopened one of the back doors of her parents Morris Traveller, fell out, and was killed. I cant gauge the effects of a three-day (i.e. quasi-eternal) hospitalization when I was twenty-two months old, when no member of my family was allowed to visit, although Im told they may be grave. It probably didnt help that I had a nonreligious upbringing. But what was worst was that I always had great difficulty sleeping, lying alone in the dark in a sagging army camp bed at the top of a large, cold house that belonged to my fathers college, with a vast, quarrelsome galvanized iron water tank outside my door, my brother and sister asleep on the floor below, and my parents two long flights of stairs (twenty-one stairs, then sixteen) away.

I thought about death almost every night, the eternal future nonexistence not only of myself but also of my family. I describe the terror briefly on page 71. Much later, in my one relatively brief period of psychotherapy, I found myself informing the therapist that I was brought up by death. It seems absurdly melodramatic, but I think it conveyed something correct. Death was the great theme of my childhood, persisting into young adulthood. I was worried by the fact that St. Giless Churchyard in Oxford, a hundred yards down the road from our house, appeared to be full up, for although I knew that it wouldnt make any difference to the eternal nonexistence of death, I wanted my family to be buried in one place for the long haul.

I often imagined, when very young, a fairy who would grant any wish. Perhaps all children do this. I knew that it would be a mistake to wish that all my future wishes be grantedin fairy stories, greed invariably backfires. I also knew that it would be no better to ask that just three wishes be grantedalthough I was tempted to give it a try. So my wish was always the samein spite of the lure of the idea of an infinitely productive sweets machine. My wish was to be able to go to sleep when I wanted.

A childish fixation on death is uncommon, like left-handedness or red hair, but not exceptional, as I found out in 1974 when I got hold of The Discovery of Death in Childhood and After by . It can be very clear in three-year-olds. In the late 1970s my daughter, then three, had a friend who was tormented by thoughts of death. His advantage, it seemed to me, was that he expressed his anxieties freely, whereas I kept mine strictly to myself. If I cried in the night out of terror and a parent eventually showed up (it was hard work to keep up the crying long enough to be heard), I would always invent a rote nightmare about being pursued by wolves. My reason for not telling my parents my thoughts about death and eternity was that although I knew I was right, I didnt want to hear it from them.

I tried to recruit the knights in armor in my wallpaper to defend me, but they had no arms against eternity. I regularly rehearsed a story in my head about a boy who lived with his mother in a large toadstool (red with white spots), in order to try to block thoughts about death. The story was unsurpassably dull. The boy would set off for school or come back from schoolI dont remember anything else. But I had and have no fictional imagination, and I couldnt keep it up for long.

Death, then, was the first of the things that deeply bothered meI mean large things, cosmic things, not the size of my ears or the baggage retrieval system at Heathrowbut it features in this book only in a relatively indirect fashion. Since then Ive been bothered all my life, and of course Im not unusual. Were all bothered in the relevant sensecosmic bother!as soon as were not simply trying to survive, keep warm, and find enough to eat, as too many human beings are. Some of us are more bothered than others, but this may be simply because we have more time for it. And we may have more time only because were insomniacs. If I had a magical, infallible botherometer, Id expect to find that Im above the eighty-fifth percentilehow far above I dont knowbut the botherometer only measures conscious, overt bother.

These pieces are about free will and con as well as death, and about what it is to be a genuine naturalist in the philosophical sensesomeone who doesnt believe in anything supernatural. Theyre about the idea of the self, the sense of having or being a self, the sense of the self in time, the narrative outlook on life, and, en passant, the unlimited nature of human credulity. Theres a mildly polemical element in the pieces about narrativity (A Fallacy of Our Age and The Unstoried Life) because theyre written against what seems to me to be an oppressive consensus. According to this consensus, anyone who lives their life in a way that is even remotely well adjusted necessarily lives it in a narrative fashion. I think this is a false and potentially harmful view, and Ive been touched by all those who have, over the years, thanked me for putting the opposing case. All of them have told me that theyd been led to believe that there was something wrong with them because they didnt live narratively in the generally approved way. Their responses have more than made up for the hostility of the pronarrative party. (What is it to live narratively? I still dont really know; I dont think I can do better than the proposal on pages 178179.)

About ten years ago it occurred to me that my own nonnarrative outlook on life (sketched on pages 5153) might have been induced by the antidepressant drug fluoxetine, which I started taking in 1995. Or rather, it occurred to me that someone who didnt believe that a nonnarrative outlook could be natural in a human being might try to trace my claims to the influence of fluoxetine. But I didnt for a moment think this could be right. I knew people taking fluoxetine who retained a strongly narrative outlook on life, and a couple of years later I found a diary entry for July 1994, written before I had ever considered the issue: No sense of narrative or development in my life. I dont have any real sense that my life extends beyond the momentthat I am a continuing person from day to day. This was always partly true but I think it has deepened considerably. What continue from day to day areproblems, things to do. They tie my life together. I have no self, really. I think that compared with others this is true. Some may find it hard to believe that a person can be oppressed by the thought of death and at the same time have little or no sense of their life as a narrative. Its easy enough to explain this, but its true that its something that needs explanation, given the way the debate about narrativity has been set up.

New York Review Books New York

New York Review Books New York