The Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology

Allan N. Schore, PhD, Series Editor

Daniel J. Siegel, MD, Founding Editor

The field of mental health is in a tremendously exciting period of growth and conceptual reorganization. Independent findings from a variety of scientific endeavors are converging in an interdisciplinary view of the mind and mental well-being. An interpersonal neurobiology of human development enables us to understand that the structure and function of the mind and brain are shaped by experiences, especially those involving emotional relationships.

The Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology provides cutting-edge, multidisciplinary views that further our understanding of the complex neurobiology of the human mind. By drawing on a wide range of traditionally independent fields of researchsuch as neurobiology, genetics, memory, attachment, complex systems, anthropology, and evolutionary psychologythese texts offer mental health professionals a review and synthesis of scientific findings often inaccessible to clinicians. The books advance our understanding of human experience by finding the unity of knowledge, or consilience, that emerges with the translation of findings from numerous domains of study into a common language and conceptual framework. The series integrates the best of modern science with the healing art of psychotherapy.

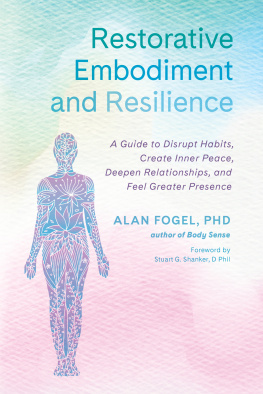

Body Sense

The Science and Practice of

Embodied Self-Awareness

Alan Fogel

Table of Contents

Chapter 2: Feelings from Within:

The Emergence of Embodied Self-Awareness

Chapter 4: Out of Touch with Ourselves:

Suppression and Absorption

Chapter 5: Shelter from the Storm: The Effects of Safety

and Threat on Embodied Self-Awareness

Chapter 8: Coming Home to Ourselves:

Restorative Embodied Self-Awareness

This book covers both the practice and the science of embodied self-awareness, our ability to feel our movements, our sensations, and our emotions. As infants, before we can speak and conceptualize, we learn to move toward what makes us feel good and move away from what makes us feel bad. Our ability to continue to cultivate and enhance awareness of these body feelings is essential for learning how to successfully navigate in the physical and social world and for avoiding injury and stress.

Embodied self-awareness is made possible by neuromotor and neurohormonal pathways between the brain and the rest of the body, pathways that serve the function of using information about body state to maintain optimal health and well-being. When these pathways become compromised, primarily as a result of physical injury or psychological stress and trauma, we lose our ability to monitor and regulate our basic body functions. The many different types of practices that can enhance embodied self-awareness that has been impaired follow some general principles that can be understood in terms of the psychophysiology of self-awareness.

Parts of this book provide concrete examples of acquisition and loss of embodied self-awareness. Other parts give case reports showing transactions between clients and practitioners in practices that enhance embodied self-awareness. In addition, parts of this book contain technical terminology involving anatomical, physiological, and psychological function in both health and illness. All technical terms are set in bold and their definitions can be found again in the Glossary at the end of the book. The more technical parts of the book can either be read in detail or skimmed, depending upon your purpose. If you would just be pleased to know that there is a scientific explanation for why you feel happier after you do yoga, even though you never talk about your emotional problems in yoga class, then forget about the technical details and focus on the examples and practices. If you are trying to convince the hospital in which you work to include more pre- and postoperative meditation classes, the physiological and anatomical details may be useful in convincing the policymakers.

You do not, however, need a scientific background to profit from the technical material in this book. It is accompanied by many everyday examples that ground the concepts in real experience and practice. There will also be boxes that focus on interesting links between body function and self-awareness (such as how yawning wakes us up to ourselves), and boxes that contain brief experiential exercises through which you can have an opportunity to get out of your conceptual thoughts and into embodied self-awareness.

Who Should Read This Book

This book is meant for people who want to learn more about how to expand their embodied self-awareness or to help others to achieve this goal. It may be read by anyone who engages in awareness-based practices and who wants to know how and why he or she is helped in some way through that practice. It can also be read by teachers, therapists, and other practitioners who want to deepen their understanding of the links between practice, awareness, and physiology.

Here is a sample of the fields in which the practitioners may find this book useful. Teachers at any level of schooling from preschool to postgraduate may use this book to justify bringing the body back into the classroom through touch, movement, and guided self-awareness meditations. Touch-based bodyworkersincluding those who work with therapeutic massage, Rosen Method Bodywork, Feldenkrais Method, and other modalities including craniosacral, structural integration, biodynamic massage, Shiatsu, Watsu, Trager, and many otherscan find explanations for the links between muscle tension, touch, relaxation, and emotional growth. Body psychotherapistssomatic psychotherapists, dance movement psychotherapists, psychodynamic psychotherapists, process psychotherapists, sex and marriage therapists, those who practice some somatically oriented forms of cognitive behavioral therapy, and many otherscan discover how embodied self-awareness has a direct impact on mental health and how cultivating their own embodied self-awareness can enhance their work with clients.

Those who work in medicine and allied fields such as nursing, pharmacology, psychiatry, rehabilitation, physical therapy, naturopathy, osteopathy, acupuncture, and chiropractics can enhance their understanding of how complementary practices to enhance self-awareness can contribute to healing and recovery from allopathic treatments. It may seem obvious that obesity, eating disorders, some forms of cardiovascular disease, and work-related injuries can arise from lack of awareness of the sensations, emotions, and movements of the body. People who overeat may not sense when their stomach is full. The stress of work situations leads to a diminished awareness of muscle tension and pain that can lead to deterioration in the long term

It is less obvious that persistent lack of embodied self-awareness can also play a role in hormonal dysfunction (as in stress disorders, disorders of sexual function, menstrual and menopausal symptoms) and immune function (leading to tumor growth and other autoimmune disorders like fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue). Awareness is medicine. Many studies show that sometimes alone and sometimes alongside allopathic medicines and interventions, physical and mental health can be improved. This is because of the direct physiological link between awareness of the body and the bodys ability to regulate its physiological functions, including hormonal and immunological processes.

Next page