Modern scholars have generally dismissed Diogenes Laertius as a mediocre anthologist, if not an ignoramus (thus the great German classicist Werner Jaeger). Even when dealing with invaluable evidence of otherwise unknown philosophical doctrines, concluded one expert, we may be said to have a museum of philosophical ideas which are pinned like beetles on pegs in glass cases to be looked at and admired, a compilation which is no more capable of furnishing an understanding of the history of these ideas than the mere examination of beetles under a glass will yield an understanding of the life of the beetle.

Renaissance readers, though not uncritical, by contrast tended to revel in the books abundance of biographical lore. In one of his Essays, Montaigne says he wished that instead of just one Diogenes Laertius there had been a dozen: for I am equally curious to know the lives and fortunes of these great instructors of the world as to know the diversity of their doctrines and opinions.

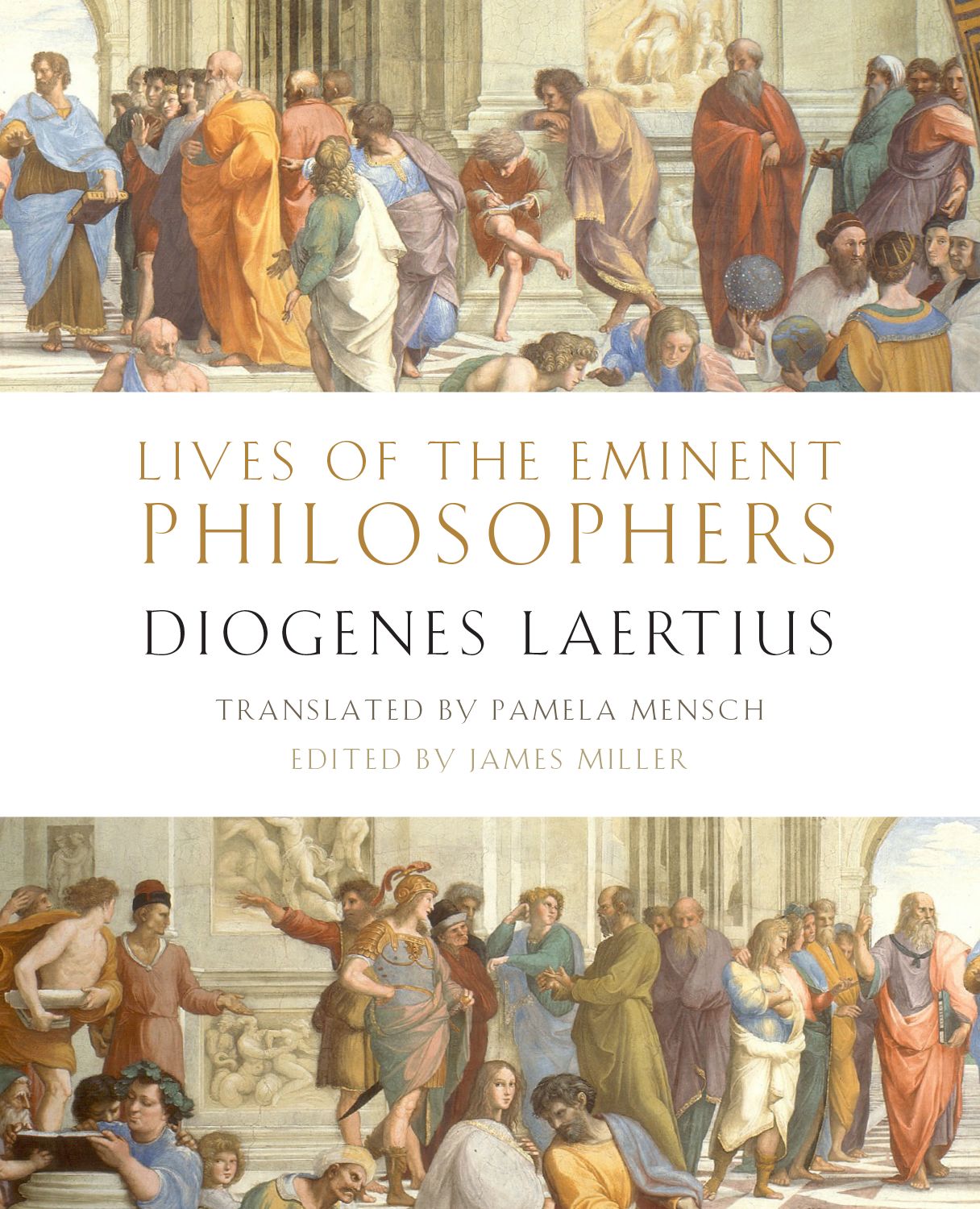

Plate with relief decoration of two philosophers debating, eastern Mediterranean, AD 500600.

From the J. Paul Getty Museum: Two seated philosophers, labeled Ptolemy and Hermes, engage in a spirited discussion. The scene has been interpreted as an allegory of the debate between Myth and Science: Ptolemy, the founder of the Alexandrian school of scientific thought, debating Hermes Trismegistos, a deity supporting the side of myth. The woman on the left, gesturing and partaking in the exchange, is identified as Skepsis. Above the two seated men, an unidentified enthroned man is partially preserved.

***

As we understand the disciplines of philosophy and intellectual history today, Diogenes Laertius practiced neither, nor was he much of a literary stylist. But Diogenes was a man on a mission, and he had the ingenuity and diligence to carry it out.

The author compiled a variety of information about all the philosophers for whom he had materialeighty-two, as it happened. All the chosen were Greek or wrote their works in Greek, since Diogenes took it as axiomatic that not only all philosophy but the human race itself began with the Greeks and not the barbarians (be they Persian or Egyptian). In addition to summarizing key doctrines, Diogenes offers a sequence of short biographiesthe most extensive set we possess.

The authors voice is direct, generally plain, even impassivethough a dry sense of humor is also at play. He appears as a stockpiling magpie, leaving little out if it fits with his own apparent fascination with whether, and how, the lives of philosophers squared with the doctrines they espoused. Evidently interested in odd and amusing anecdotes, the more controversial the better, Diogenes sometimes notes the bias of his sources, but only rarely does he make an effort to evaluate their plausibility or the authenticity of the letters and other documents he reproduces. Although he obliquely comments on his Lives through a series of epigrams by others and poems of his own, filled frequently with puns and wordplay meant to amuse, he almost never praises or criticizes directly the characters he describes, nor does he venture any unambiguous opinion of his own about how one might best undertake philosophy as a way of life. His philosophical views (if he had any) are obscure.

The treatment of individual philosophers is uneven, ranging from an interminable list of categorical distinctions in the chapter on Plato to the verbatim citation of several works by Epicurus in his chapter on that philosopher. Some chapters are barely one paragraph long; others go on for pages. Sometimes a reader feels as if the author had simply dumped his notes on a table. Yet even if the overall order of the books and some of the biographies was still unsettled at the time of his death, the text as we have it is never haphazard, since the material on individual philosophers is sorted more or less carefully into sections on genealogy, anecdotes, apothegms, doctrines, key works, and (almost always) a necrology, just as each of the works ten books is more or less plausibly organized by schools and lines of putative succession.

As a result of this encyclopedic format, it has long been the habit of most scholars and ordinary readers to dip into Lives of the Eminent Philosophers as needed, treating it like a reference work (however strange and unreliable).

But if instead one reads the entire text straight through (as there is some evidence the author intended), a not unwelcome bewilderment descends.

Despite some rough parts and missing passages, we behold a meticulously codified panorama of the ancient philosophers. Through the eyes of Diogenes, we watch them as a group living lives of sometimes extraordinary oddity while ardently advancing sometimes incredible, occasionally cogent, often contradictory views that (to borrow a phrase from Borges) constantly threaten to transmogrify into others, so that they affirm all things, deny all things, and confound and confuse all thingsas if this parade of pagan philosophers could only testify to the existence of some mad and hallucinating deity.