This book made available by the Internet Archive.

To my wife, Lillian R.O.B.

To Harwood Rhodes, from a grateful student G.S.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank our wives, Lillian Becker and Maureen Sugden, without whose love, help, and patience this book would never have been completed. We also wish to acknowledge the contributions of editor Maria Guarnaschelli and copy editor Bruce Giffords, as well as Julie Weiner, the editor who first saw promise in this project, and Susan Schiefelbein, who began a draft of the work several years ago. In addition, we are grateful to friends, colleagues, researchers, and sources too numerous to list. To those not mentioned in the text we hereby offer our heartfelt thanks.

Co-author's Note

Bob Becker spent almost thirty years working on the substance of this book. I spent not quite two in helping to organize the material and fit the words together. Therefore I have chosen to tell the entire story from his point of view. Unless otherwise noted, "I" refers to him and "we" to him and his collaborators in research.

Gary Selden

Undercurrents.in Neurology 85

Conducting in a New Mode 91

Testing the Concept 94

5 The Circuit of Awareness 103

Closing the Circle 103

The Artifact Man and a Friend in Deed 106

The Electromagnetic Brain 110

6 The Ticklish Gene 118

The Pillars of the Temple 118

The Inner Electronics of Bone 126

A Surprise in the Blood 135

Do-It-Yourself Dedifferentiation 141

The Genetic Key 144

7 Good News for Mammals 150

A First Step with a Rat Leg 152

Childhood Powers, Adult Prospects 155

Part 3 Our Hidden Healing Energy 161

8 The Silver Wand 163

Minus for Growth, Plus for Infection 163

Positive Surprises 169

The Fracture Market 175

9 The Organ Tree 181

Cartilage 187

Skull Bones 188

Eyes 190

Muscle 191

Abdominal Organs 192

10 The Lazarus Heart 196

The Five-Alarm Blastema 197

11 The Self-Mending Net 203

Peripheral Nerves 206

The Spinal Cord 207 The Brain 213

12 Righting a Wrong Turn 215

A Reintegrative Approach 219

Part 4 The Essence of Life 227

13 The Missing Chapter 229

The Constellation of the Body 233

Unifying Pathways 238

Contents

Breathing with the Earth 243

The Attractions of Home 250

The Face of the Deep 255

Crossroads of Evolution 261

Hearing Without Ears 264

Maxwell's Silver Hammer 271

Subliminal Stress 276

Power Versus People 278

Fatal Locations 284

The Central Nervous System 284

The Endocrine, Metabolic, and Cardiovascular

Systems 288

Growth Systems and Immune Response 292

Conflicting Standards 304

Invisible Warfare 317

Critical Connections 326

Postscript: Political Science Glossary 348

Index 353

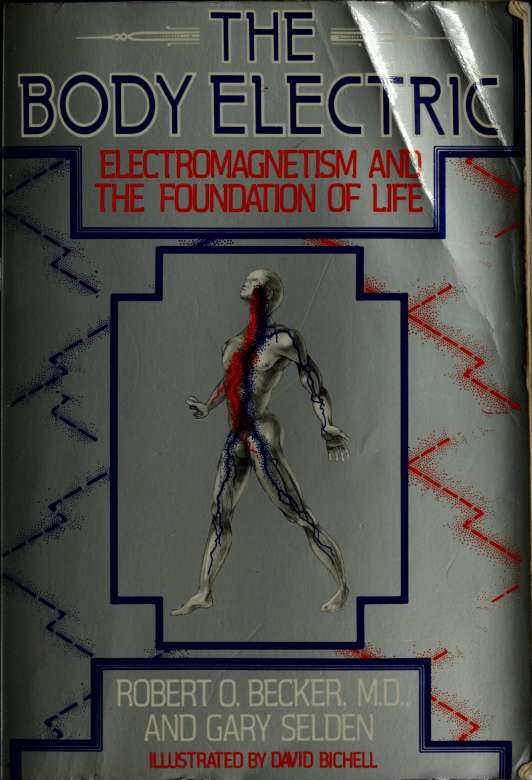

THE

BODY

ELECTRIC

Introduction:

The Promise of the Art

I remember how it was before penicillin. I was a medical student at the end of World War II, before the drug became widely available for civilian use, and I watched the wards at New York's Bellevue Hospital fill to overflowing each winter. A veritable Byzantine city unto itself, Bellevue sprawled over four city blocks, its smelly, antiquated buildings jammed together at odd angles and interconnected by a rabbit warren of underground tunnels. In wartime New York, swollen with workers, sailors, soldiers, drunks, refugees, and their diseases from all over the world, it was perhaps the place to get an all-inclusive medical education. Belle-vue's charter decreed that, no matter how full it was, every patient who needed hospitalization had to be admitted. As a result, beds were packed together side by side, first in the aisles, then out into the corridor. A ward was closed only when it was physically impossible to get another bed out of the elevator.

Most of these patients had lobar (pneumococcal) pneumonia. It didn't take long to develop; the bacteria multiplied unchecked, spilling over from the lungs into the bloodstream, and within three to five days of the first symptom the crisis came. The fever rose to 104 or 105 degrees Fahrenheit and delirium set in. At that point we had two signs to go by: If the skin remained hot and dry, the victim would die; sweating meant the patient would pull through. Although sulfa drugs often were effective against the milder pneumonias, the outcome in severe lobar pneumonia still depended solely on the struggle between the infection and

the patient's own resistance. Confident in my new medical knowledge, I was horrified to find that we were powerless to change the course of this infection in any way.

It's hard for anyone who hasn't lived through the transition to realize the change that penicillin wrought. A disease with a mortality rate near 50 percent, that killed almost a hundred thousand Americans each year, that struck rich as well as poor and young as well as old, and against which we'd had no defense, could suddenly be cured without fail in a few hours by a pinch of white powder. Most doctors who have graduated since 1950 have never even seen pneumococcal pneumonia in crisis.

Although penicillin's impact on medical practice was profound, its impact on the philosophy of medicine was even greater. When Alexander Fleming noticed in 1928 that an accidental infestation of the mold Penicillium notatum had killed his bacterial cultures, he made the crowning discovery of scientific medicine. Bacteriology and sanitation had already vanquished the great plagues. Now penicillin and subsequent antibiotics defeated the last of the invisibly tiny predators.

The drugs also completed a change in medicine that had been gathering strength since the nineteenth century. Before that time, medicine had been an art. The masterpiecea cureresulted from the patient's will combined with the physician's intuition and skill in using remedies culled from millennia of observant trial and error. In the last two centuries medicine more and more has come to be a science, or more accurately the application of one science, namely biochemistry. Medical techniques have come to be tested as much against current concepts in biochemistry as against their empirical results. Techniques that don't fit such chemical conceptseven if they seem to workhave been abandoned as pseudoscientific or downright fraudulent.

At the same time and as part of the same process, life itself came to be denned as a purely chemical phenomenon. Attempts to find a soul, a vital spark, a subtle something that set living matter apart from the nonliving, had failed. As our knowledge of the kaleidoscopic activity within cells grew, life came to be seen as an array of chemical reactions, fantastically complex but no different in kind from the simpler reactions performed in every high school lab. It seemed logical to assume that the ills of our chemical flesh could be cured best by the right chemical antidote, just as penicillin wiped out bacterial invaders without harming human cells. A few years later the decipherment of the DNA code seemed to give such stout evidence of life's chemical basis that the double helix became one of the most hypnotic symbols of our age. It seemed the final proof that we'd evolved through 4 billion years of chance mo