W hat is soccer?

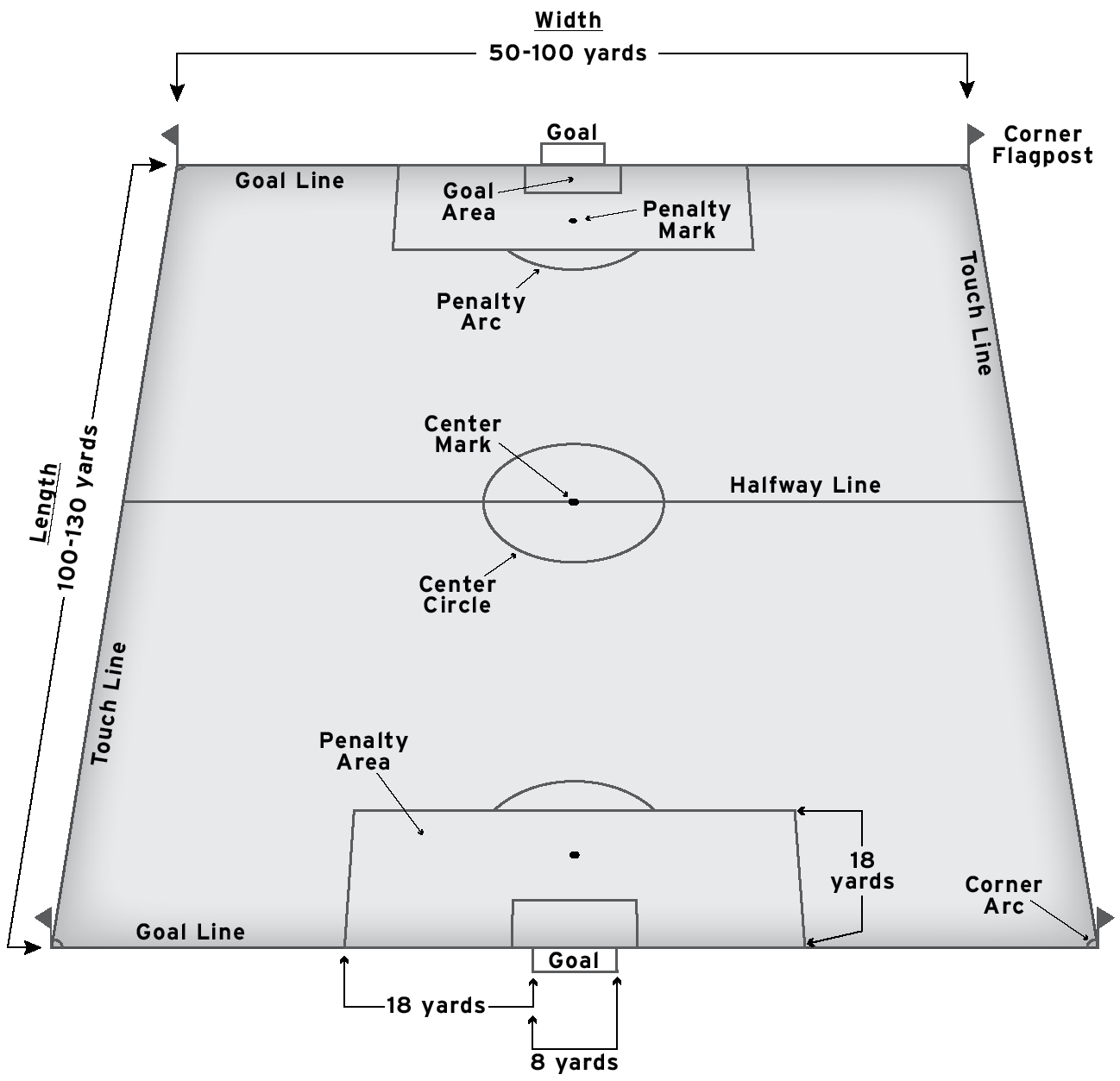

It is a game you play on a rectangle of ground bracketed by two goals, one at either end. That shape is everywhere. Fly into almost any city in the world and look down, and you will see itprobably with people running back and forth, whether it is morning, midday, or night.

Many other soccer games are played in improvised spaces: a bit of grass in a park in Brooklyn or Rome, a courtyard in a housing project, a stretch of rocky dirt in a shantytown in Buenos Aires or Kinshasa, a rooftop in Tokyo, a black sand beach at the end of the road in GrandRivire, Martinique.

Soccer is possibility. In Chile there is an expression, rayando la cancha, which means marking the field. It is what you do to transform a place into a soccer pitch, an action so common in Chile that the expression can be used to describe any kind of beginning.

All you need is a ball. If you dont have one, you can make one. And even if you dont have one, you can play. That is what a group of boys do in the film Timbuktu, by Mauritanian director Abderrahmane Sissako, when the Islamist group that has taken over their town bans the sport and takes away their ball. In one of the most beautiful sequences I have seen in any film, the boys play the game anyway. They dribble and tackle. Take a penalty kick. Score a goal. Celebrate.

The ball is unnecessary, in the end, because soccer, more than anything, is an idea.

Soccer is life. In her account of traveling the world looking for pickup soccer games to join, former US collegiate soccer star and filmmaker Gwendolyn Oxenham writes of visiting a park in Rio de Janeiro. There, waiters gather after their restaurants close. They start playing at midnight and often keep going until dawn, delighting in the movement and creativity that defines Brazilian futebol. I wash the dishes, I sweep the floors, I put the chairs up on the table, one player tells her, and then I come here to play, to live. Oxenham understands. For as long as I can remember, she writes, futebol has been how I come all the way alive.

Soccer comes from a specific place and time: the schools and universities of nineteenth-century Great Britain. The Laws of the Game, which still govern how soccer is played, were first set down in 1863. Because of the countrys dominant global presencenot only through the British Empire but also through the British merchants and companies based outside the coloniesthe game was soon on the move. It spread quickly. By the end of the nineteenth century, it was being played in Europe, Latin America, Southeast Asia, and throughout much of Africa, even in areas outside the British Empires sphere of influence. The game has shown a remarkable capacity to flourish nearly everywhere it has taken root. Played in Senegal, it seems as completely Senegalese as any other form of local culture. Soccer is absolutely German. It is absolutely Argentinean. It is absolutely Haitian. And, of course, it is perhaps above all absolutely Brazilian. In fact, the English often have to remind the rest of us that they were the ones who invented it. As perpetually beleaguered English fans know, at least when it comes to global competition, having invented the game hasnt given them much of an advantage.

There are good reasons for soccers universal appeal. It is a simple game, easy to learn and grasp. A few instructions, a finger pointed at the goal, and off you go. It is democratic in this sense, and also in the way that it accommodates all kinds of body shapes and sizes. In fact many great soccer players are of slight or short physique. I love the way that small men can destroy big men, writes the novelist Nick Hornby, an ardent fan of the English club Arsenal. Strength and intelligence have to combine to make a great player.

There are a surprising number of small goalies, for instance. Their ability to see and move, and the size of their personalities, is more important than their physical size. If you put Lionel Messi, often considered the best forward in the world, in a suit, hed look at home in a cubicle in some office park working as an accountant. One of the greatest strikers of all time, the Brazilian Manuel Francisco dos Santos, known as Garrincha, had bowed legsan inheritance from disease and hunger suffered in his youth. As a result, he moved, and dribbled, in an unusual way. That was part of his brilliance, enabling him to constantly outsmart defenders. In his autobiography, the great Argentinean player Diego Maradona recalls how the president of the Italian soccer club Juventus

There is one major check on this openness to diverse body types. Soccers global institutions, along with the soccer industry and media, are dominated by men. Sexism shapes the practice and representation of soccer everywhere, and in turn soccers gender divisions often play into and confirm stereotypes. Womens soccer struggles to gain equal recognition and financial support. The policies and practices that have excluded women depend on the idea that soccer is fundamentally male and that women are interlopers, or at least newcomers, in the sport.

This is an illusion. In fact, women have played soccer as long as men. In the early twentieth century, womens soccer was hugely successful in England, drawing massive crowds to stadiums. Then, in 1921, the English Football Association banned women from using its fields and stadiums, essentially driving womens soccer underground. There were similar decisions made in other countries. But, in the face of concerted opposition, women never stopped playing. In 1970, the first Womens World Cup was organized independently in Italy. The next year, the Womens World Cup was played in Mexico City, in the Azteca stadium, where Brazil had famously won the mens World Cup the year before. Footage and photographs from the womens games show a packed stadium. The 1971 Womens World Cup has been almost totally forgotten, even though the crowd appears to have been larger than that at the 1999 Womens World Cup final at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, Californiausually cited as the womens soccer game that drew the largest live crowd in history. These are reminders, however, that soccer isand has always beena womens sport.